‘We’re Not Asking for Special Treatment’: Coin Center on the Proposed IRS Broker Rules

This interview is part of CoinDesk’s Tax Week, presented by TaxBit. It was excerpted from The Node newsletter.

The so-called broker rule, laid out by the IRS in a tax reporting proposal has been at times called unconstitutional, unprecedented in scope and an existential threat for the cryptocurrency industry. Indeed, by expanding the definition of a broker — a well-defined term in the context of traditional finance, with some analogues in the digital asset industry — to just about anything that touches code in crypto, the proposed rule would likely be “overbroad.” The rule has been officially adopted, the IRS is holding back-to-back hearings on the proposal, and has extended the public comment period — over 120,000 responses have already been filed.

One of those public comments was filed by industry advocates at Coin Center, which argued the broker rule is not only impossible to comply with but also likely a violation of U.S. crypto users and developers’ civil liberties. CoinDesk reached out to Coin Center director of research Peter Van Valkenburgh to discuss where the IRS’ proposal comes from, how to fight it and whether there are any silver linings to this existential crypto crisis.

What do you make of the thousands of comments submitted to the IRS?

Well, I mean, this important topic. For decades we’ve had certain types of third-party tax reporting where the person is obligated to do the reporting is in a position of trust (i.e. traditional securities brokers or other financial intermediaries), and this is the first time that, through rulemaking, the IRS would be extending third-party reporting obligations to people who don’t have traditional financial customer relationships at all to software developers.

I think rightfully a lot of people are alarmed about that. Some people filing comments might see their business become non-viable. They were just publishing software tools, and now have to create a relationship with customers in order to report information about their customers even though they didn’t have customers before.

For Coin Center, this is a clear civil liberties issue. Our comment letter focuses on the unreasonable violation of people’s privacy and unreasonable obligation on software developers to be forced to collect information and report it, which is a type of compelled speech.

A term that seems to be coming up again and again is unprecedented. I was wondering if there is anything like this in either U.S. tax law or global policy?

It is unprecedented. It’s important to articulate this clearly to people who haven’t followed the debate, which started two years ago when Congress first passed the relevant statute in the Infrastructure Act that triggered this rulemaking. Coin Center and other advocates have no issue with third-party tax reporting.

I’ve always said if it walks like a duck and it quacks like a duck, it’s a duck. A typical digital asset brokerage, like Coinbase, has a bunch of contractual relationships under common law — the exchange is in a position of trust vis-à-vis its customers and its customers’ assets. And so just like a typical securities broker, or broker dealer regulated by the Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), it makes sense to obligate a digital asset broker dealer with the same reporting obligations of a traditional asset dealer.

We’re not asking for special treatment. If anything, the IRS took too long to come up with common sense guidance for how obvious brokers in the crypto space like Coinbase should be obligated to report. The IRS already had the authority, they didn’t need Congress to act.

In early draft language of the Infrastructure Act, there was statutory text that specifically called out noncustodial and decentralized exchanges to report, leading to a big fight. They created terms for noncustodial or decentralized platforms that needed to be defined so people could understand their obligations under the law.

Further, decentralized exchanges exist, which are just software. There’s no public policy justification for obligating software developers to collect information on their users. And indeed, the opposite. It’s unconstitutional. It’s a First Amendment compelled speech issue and it’s a Fourth Amendment warrantless search and seizure issue.

During the original fight, the draft language was thrown out and replaced with a much narrower definition of broker which looks very similar to the definition of broker in the traditional financial services industry. There was even a colloquy on the floor of the Senate, where Senator Portman — who first introduced the problematic language — said we have no intention to cover people who are not brokers as traditionally understood.

In the context of the brokerage rule: the thing we’re asking for is to just be left alone

And so we had this fight already. And we thought we won. And then the IRS comes out with this rulemaking that acts as if the original discussion draft language never got thrown out.

It almost seems like you’re saying there’s a version of this proposal that could be workable, but it may already be enshrined in U.S. law.

So that’s right. The existing standard for who is a broker for third-party tax reporting obligations hinges on a few definitions in the existing tax code. The big ones being who is a customer and what does it mean to “effect” transactions on behalf of a customer.

If you look at the tax code, those definitions hinge on the notion of an agency-like relationship, wherein they act in a customer’s best interest when going into the market to effect transactions on their behalf. There’s no reason I would say why you can’t just apply that same agency standard to persons acting as agents of customers for buying and selling crypto rather than just securities.

Now when you have a software developer, or you know the developers of a decentralized exchange, those people write software tools. And in the usual case, they have no agency relationship with their users. They don’t have customers in the traditional sense. And so I think it’s inappropriate to apply the same kind of reporting to those kinds of people.

Could you explain why DeFi protocols cannot provide the information the IRS is asking for?

The long and short of it is there’s two different ways to run a business in this space. You can run a business where you have a relationship with your users and there’s terms-of–service or other legally-binding instruments that obligate you to act on behalf of your users. And the alternative is, you could be in the business of just writing software that people use on their own to manifest their desires in buying and selling and trading. There are some businesses somewhere in between, but as a general rule, there are businesses that only publish software.

In our comment letter, we compared it to the government wanting to know which books Americans are buying and reading. And so in order to find that out, rather than obligating booksellers to collect information (which would also be constitutionally dubious), we’re going to force authors to have in person book signing events where they’ll be able to meet their readers and report on their reading habits.

It’s an extremely overbroad and constitutionally dubious regime, because if you’re just writing software you don’t have a personal relationship with your users.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but the metaphor explains the privacy concerns too, because readers have a right to not having their reading preferences reported on? Or is it more complicated?

I mean, that’s a compelling argument in and of itself. But there’s Fourth Amendment concerns in that, going from first principles, third-party reporting is a form of mass surveillance. We struck this bargain many, many years ago in traditional financial services where as a society we decided corporations don’t have absolute rights to privacy because corporations are regulated entities and we want to make sure they’re not abusing their customers.

So we allow for a certain amount of searches of their records to ensure that the laws are being followed. And in many cases we allow for the search and surveillance of businesses without warrants, which is a process that can be abused.

However, obligating persons who are not financial intermediaries, persons who are not in a position of trust and persons who historically have had no regulatory apparatus — like the financial regulatory apparatus in the securities, commodities or money services businesses context — regulating those people or obligating those people rather to do third party reporting is a whole different kind of search and seizure regime.

It’s just manifestly unconstitutional under the Fourth Amendment, because it goes well beyond the bounds of any reasonable administrative search. It obligates these entities to collect information as a quote unquote part of their business, who would never be part of their business.

If you’re in the business of designing smart contract software and publishing it to an address on the Ethereum blockchain, such that people can use that smart contract to trade assets, there’s no part of your business, irrespective of how profitable your business is, no part of your business makes it logical or sensible for you to collect personal information on the people who use that smart contract.

A big part of the reason people want to use DeFi is because they’ve lost trust in the financial system. And forcing software developers to become the trusted entities that people are trying to escape is deeply anti-innovation, deeply bad for customer privacy and civil rights.

How does 6050i relate to the broker rule?

When the Infrastructure Act passed Congress, it created two big new tax reporting regimes with respect to crypto. The other one is this broker rule and the other was 60501, which I called “cash and coin reporting.” 6050i is the part of the tax code that says if you’re a business and you are paid $10,000 or more in cash and coins, you need to collect the name, physical address and taxpayer ID of the person paying you and file a report to the IRS and FinCEN.

Coin Center objected to those reporting requirements because the same Fourth Amendment analysis we just went through. It’s been found constitutional for banks to collect records about their bank customers, because they’re in this business of being a financial institution and they get certain favors from the government by going into that business. They get to operate as part of the payment system and access to the Federal Reserve. They have to compy to better ensure the safety of their customers and prevent the use of their business for money laundering purposes or tax evasion purposes. The trade off is quite reasonable: some amount of surveillance and government control in exchange for the opportunity to run a highly lucrative business where customers trust you with their money.

Where there’s not the same trade off, like when we’re talking about ordinary small businesses, it’s a different calculus. Why would I forego my right to privacy because I’ve decided to buy something from a small business?

When Congress decided to amend the Infrastructure Act to make it apply to crypto transactions: Now we have a situation where it’s going to happen a lot. People often get paid $10,000 or more in crypto. Earning a bitcoin block reward if you’re a bitcoin miner, is in theory, a reportable transaction, but good luck coming up with whose name and physical address and social security number you’re supposed to put on that form when you get paid by the Bitcoin network.

Coin Center filed suit, too?

We’re fighting 6050i in the courts. We have a lawsuit we’re a co-plaintiff, because we’ve received transactions of $10,000 or more as donations and we don’t want to collect this information about our donors. We’re allowed to have an anonymous group of members as an association. Once the government starts having lists of who’s a member of which political association, the government starts targeting people. We think we’ll have an earlier dismissal overturned at the Circuit Court, but will then have to go back to the District Court to litigate the case on its merits.

There are supposedly issues with how the IRS will collect this information too?

There are actually a lot of issues with how the IRS will collect 6050i forms. Chief among them is that it is not allowed to send them to FinCEN, which is how it does traditional coin and cash reporting because of quirks in how the law got amended. Further, it may not be prepared to collect these forms next tax year, which is a whole separate mess.

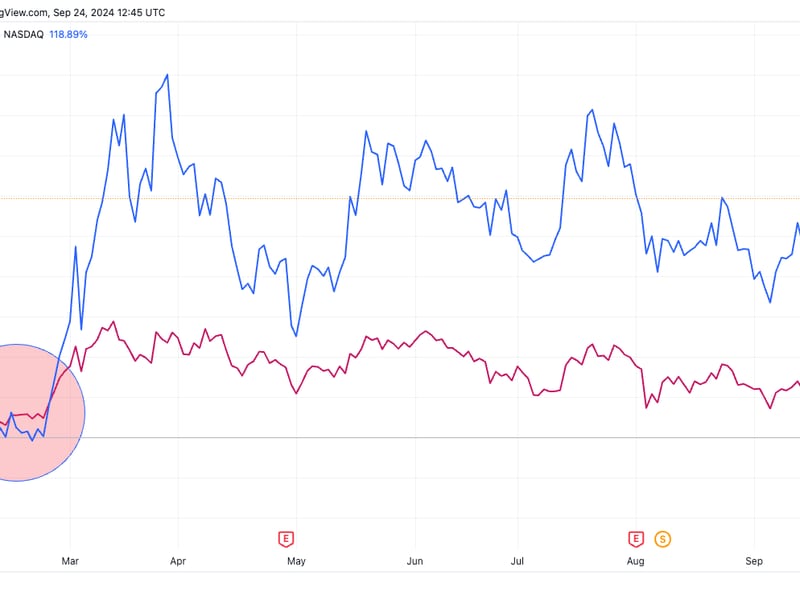

As for the broker rule, it’s going to lead to a massive amount of data. Even the IRS has admitted that it’s going to double or even triple the number of reports it gets and have said its not prepared. Maybe its saying that because it wants to convince Congress to give them more money. That’s fair. But I think they’ve sort of shown their own hand here that they are creating a new reporting obligation that is just inappropriate — it is just too much private data for any entity to really be able to handle responsibly.

Big databases get hacked. And this is going to be an insanely sensitive database because it’s going to be a list including home addresses of people who have large amounts of crypto.

Will this list improve tax compliance?

I don’t think so. Like if you really want to improve tax compliance, you should just make it easier for obvious crypto brokers like Coinbase to do third-party reporting, which is the thing that we’ve been asking the IRS to do for years. And instead of doing that, we’re obligating tens or hundreds of thousands of people, like software developers, to start collecting information in a way that doesn’t make any sense.

Is there an argument to make that the IRS thinking about bespoke rules at all for crypto is a positive development?

100%. Putting aside the data concerns, cybersecurity risks, civil liberties offenses. It in a sense is helping to clarify that brokers dealing in digital assets are otherwise just like a securities broker, except they’re dealing in digital assets. That alone would be a huge win for American crypto policy and American tax policy, because Coinbase and Kraken and others have wanted this clarity for a long time.

There is also a First Amendment argument against the IRS rulemaking. To someone who’s not a constitutional lawyer, it might seem a little strange but it’s pretty straightforward. In a nutshell, any kind of mandatory disclosures is a type of compelled speech. We’re free in this country to not have to worry about getting approval of the things we speak and not have a government bureau tell us that we have to say certain things.

Now, purely non-controversial, factual disclosures can be compelled from businesses without violating the First Amendment. Like in advertising, the government can force tobacco companies to say the Surgeon General has found that cigarettes cause cancer. What you can’t do is force companies to express a viewpoint or express something not strictly factual.

And the interesting thing about a third-party reporting requirement for software developers (rather than traditional brokers), is that by taking down information on their customers that they ordinarily do not collect and reporting it, they’re not just reporting noncontroversial facts at that point. Traditional brokers collect this information anyway, so reporting is noncontroversial.

You’re also forcing them to write a whole bunch of software. Not only that, but it’s software with a viewpoint behind it: that all transactions should actually be intermediated by trusted entities who collect information on behalf of the government. Software developers in DeFi have the opposite viewpoint. They don’t want this information. They don’t have customers in the traditional sense, and they don’t want to have customers. They want to build tools that respect users’ privacy.

And so, third-party tax reporting is compelled speech. It would be a compulsion on software developers to write code that goes against their deeply held political and social beliefs.

The Supreme Court has recently vindicated the rights of software developers even in the online context in a case involving 303 Creative LLC, where Colorado was going to obligate web developers to create websites for clients in the context of same sex marriage.

As a privacy advocate and crypto advocate and cypherpunk: Does the fact that we’re talking about crypto legality at all a sign the game itself is lost?

The point you’re making is very true. There’s a related topic: banking crypto, right. I have a lot of trouble coming up with principled policy arguments for why we should find a way to fix that. You don’t have a right to a bank account as an American. Maybe you shouldn’t have talked about getting rid of the banks for all this time! To me, if the only thing that allows this technology to work is your ability to connect your bank account to your bitcoin exchange, then this technology doesn’t work. And so and so I’m with you there, like I’m not gonna go advocate for a constitutional right to bank Bitcoiners.

On the other hand, in the context of the brokerage rule: the thing we’re asking for is to just be left alone. We’re not asking for the government to give us a right to a bank account. We’re just asking for our First and Fourth Amendment rights to be vindicated, such that the people who write our software for us aren’t forced to spy on us. It’s a pretty reasonable thing to ask the government.