The Real Reason Federal Reserve Chair Powell Retired “Transitory”

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell’s decision to retire the term “transitory” offered some insight into how the Fed and global monetary system really work.

There was much more said in Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell’s recent testimony, given before the U.S. Congress on November 30, than met the eye, but you have to know about the Fed’s actual influence in order to read between the lines. Headlines of Powell retiring the term “transitory” will lead many casual observers to believe Powell admitted that he was wrong about the temporary nature of price increases. In reality, he was making a point about the need for clear messaging.

As a disclaimer, this won’t be your typical warning about impending hyperinflation. This is a sober look at the Fed from an empirical position, which also happens to be contrarian right now: that the Fed is not just perpetually wrong, it is not central and doesn’t matter much.

Below, I’ll comment on three different answers given during Powell’s testimony, that I think shine a light on how the Fed and the global monetary system works. These three segments were also featured on Bitcoin Magazine’s “Fed Watch” podcast episode 73 (video and audio), if you’d like to dive deeper.

Retire The Term Transitory

Our first quote is where Powell retires the term “transitory”:

“I think the term transitory has different meanings to different people. To many it carries a sense of short lived. We tend to use it to mean that it won’t leave a permanent mark in the form of higher inflation. I think it’s probably a good time to retire that word and try to explain more clearly what we mean.”

–Powell

You’ll notice that he is not changing the intended nature of his inflation forecast, only that the word transitory is confusing. Powell still views inflation as transitory, but the term has been distorted and misrepresented by the financial press and internet commentators to the extent that the Fed’s messaging is no longer clear.

That’s a pretty big deal, because Fed messaging is its primary monetary policy tool. The chair forms narratives months in advance, using Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) minutes, press conferences, speeches and sound bites from Fed governors. The constant reporting is like a mantra, repeated daily in the financial press, droned on and on into the heads of investors.

“Wait, messaging is their primary tool?” you might ask. Absolutely. The Fed’s other monetary policy tools, like asset purchases (or quantitative easing [QE]), have little to no demonstrable effect on the market. Not only do we have empirical evidence in metrics like velocity, lending and bond prices in the U.S., we have examples like in Japan, which is several years ahead of the Fed, using the exact same script.

It is the belief in the power of the Fed’s tools, and clever use of messaging, that make these other tools seem to work. Does this distinction matter? Should we care if it is the market’s expectations or the actual monetary tools that cause market changes? I’d say so. Realizing that messaging is the tool allows us to disregard unimportant metrics and filter the signal from the noise.

Simple enough, if “transitory” is causing mixed signals, it must retire the term. The message is the tool.

Long-Running Global Forces On Interest Rates

Let’s go to the second quote, this one about interest rates. Here, Senator Mike Rounds asked if Powell considers the U.S. government’s creditworthiness when the Fed makes interest rate decisions.

Baked into the question is a complete blind acceptance that the Fed is able to set interest rates. Rounds’ quick follow up showed a cognitive dissonance. He asked if Powell predicts interest rates on U.S. treasuries to rise over the next 18 months. That question doesn’t make sense if he thinks the Fed sets interest rates.

It makes me think of “A Few Good Men,” when Tom Cruise asks Colonel Jessup, “Why did Santiago have to be reassigned, if you said he was not to be touched, and your orders are always followed?” If the Fed sets interest rates, and high interest rates threaten the national debt, why would Powell set rates higher?

I realize this might be a touchy subject for many who have bought into the power of the Fed to set interest rates, but Powell’s answer should make you at least question your assumptions.

“Generally, that [higher rates] is something that staff has been forecasting ever since I got to the Fed, 10 years ago and it really hasn’t happened. What’s happened, as the secretary mentioned, you have a series of long-running global forces that are leading to lower sustained interest rates. How long will they last? It’s very hard to say, but for now we have a lower inflation trend — obviously currently, at the moment we have high inflation —but for many years we’ve had low inflation, and the markets are baking in a return to lower inflation.”

–Powell (emphasis, the author’s)

I haven’t seen any analysts give the first half of this statement a second look, but it’s the juicy part. Powell plainly admitted that the Fed is not in control of interest rates. That “long-running global forces” are in charge and Fed policies only have, um… transitory effects.

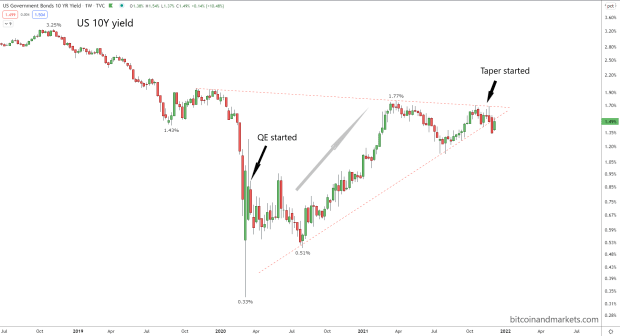

And which direction do those effects take the market? According to some, QE is supposed to keep interest rates down, but in the midst of this round of QE, rates rose. And the start of the taper coincided with rates falling below the long-term trend line.

The idea that interest rates are outside of the Fed’s control is central to the global dollar (eurodollar) thesis of the monetary system; the majority of the global financial system is outside the U.S., where global capital flows are in charge. The Federal Reserve is not central, and its traditional tools have very little effect. That is why messaging is so important.

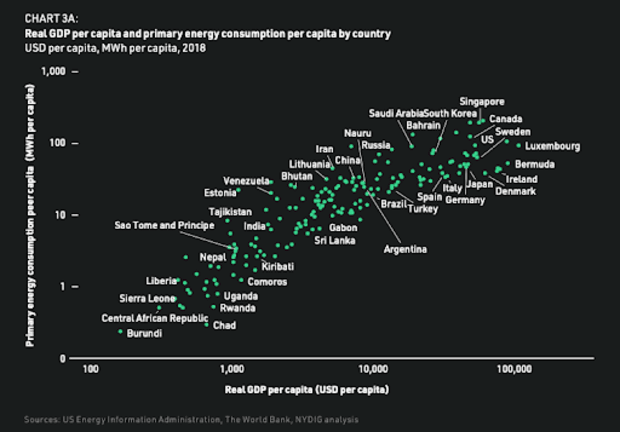

“Long-running global forces” are the deflationary forces I often discuss. Their main cause is debt saturation and diminishing marginal revenue product of debt, in other words, the growth you get from the next dollar in debt is approaching zero.

There are other, less talked about and less understood causes of global, low interest rate forces. Demographics is a big one. China, Japan, Europe and Russia are facing rapidly-shrinking populations. They have already passed the point of no return, fewer people to produce and consume in the coming decade, resulting in the natural shrinking of their economies; that is above and beyond the debt saturation mentioned above.

Another force boosting demand for high-quality securities is rising geopolitical risk. As geopolitical risks rise, whether that is foreign troops on your border or trade wars, investment and economic activity are negatively impacted. As the U.S. liberal trade order ends, borders will become less certain, risks of regional war increase and legitimacy of international institutions like the United Nations, World Trade Organization, World Health Organization, World Court, North Atlantic Treaty Organization, International Monetary Fund, etc. are undermined.

A global low interest rate environment means that there is high demand for safety relative to other uses for that capital elsewhere in the economy. Opportunities dwindle and rates drop. To answer Powell’s question, “how long will they last?” — until we replace the money.

Supply-Side Inflation And Taper

The last segment we’ll examine is a question and response to Senator John Kennedy about inflation forecasting and the speed of taper.

“I think what we missed about inflation was we didn’t predict the supply-side problems. And those are highly unusual and very difficult, very non-linear, and it’s really hard to predict those things. But that’s really what we missed, and that’s why all of the professional forecasters had much lower inflation projections.”

–Powell

Are supply-side problems money printing? If not, why do we count their effects as inflation?

Price rises are not an evil thing. The inflationist narrative that rising prices are “everywhere and always inflation” is bothersome. Prices change all the time, both decreases and increases are a natural phenomenon. Price increases that are a result of supply-side issues are not necessarily bad.

Perhaps modern technology and globalization have poisoned a couple of generations to think that prices should always go down, not up. Even in a sound money system that is facing the global deflationary pressures of today, prices would increase at times. They’d probably increase faster in the current environment, because sound money has a way of flushing malinvestment out faster.

Prices convey information in the market. Changing prices tell us things about supply and demand. If supply chain bottlenecks are forcing prices up, it tells market participants that more capital or innovation is needed in those areas, and it adds the incentive to move products or services into sectors with relatively high prices, from areas with less potential for profit.

Price changes due to supply-side effects are hard to predict, as Powell said, that’s true. This is because the issues could be on the other side of the world, or there could be regulatory roadblocks, or any number of smaller things that hinder the market from moving capital where it’s most needed. Supply-side problems shouldn’t be viewed as inflation, they are imbalances. It’s a classification error.

This highlights the deficiency in using prices as inflation. If the Fed was printing money, it could just say, “we printed 5% more money, so inflation is 5%.” The reason it can’t do that and must rely on an index of prices is exactly because it doesn’t print money. Since at least former Federal Reserve chair Alan Greenspan, Fed chairs have admitted that they don’t really know what the supply of money is.

Back to Powell: He said in the third clip, its purchases are “accommodation,” not printing. Its purchases are intended to add a special type of reserves to the banking system to encourage banks to lend, which is where money printing actually happens.

If M2, M1 or base money were the important metrics for the supply of money, inflation would be much more predictable. Yet, since QE started back in 2009, the massive inflation warned of has never appeared. Finally, in 2021, when we get mild price increases of 5% to 6%, a full 12 years after QE, it just so happens to coincide with the worst supply chain disruption in 50 years.

Here is the other interesting part of this last exchange:

“We now look at an economy that is very strong and inflation pressures that are high. That means it’s appropriate for us to discuss at our next meeting, that’s in a couple weeks, whether it’d be appropriate to wrap up our purchases a few months earlier.”

–Powell

Again, this is an example of messaging or expectation management. Listeners go away with the impression that the economy is overheating with inflation, so much so that the Fed has started pulling back some of its powerful monetary weapons and thinks it might have to be even more aggressive.

We know now that the Fed did double its rate of taper, to wrap up in March 2022. What we are starting to hear is talk about a “taper tantrum” where markets pull back as the Fed supposedly withdraws its stimulus. However, economic conditions have been getting worse for months now, it has very little to do with the taper.

The Fed reacts to the global economy, not the other way around. In fact, that is one reason the Fed decided to taper in the first place, because the economy was getting worse and that wouldn’t make sense if they were in full QE mode. Hence, the speed of the taper doesn’t matter much, it is all about the signaling.

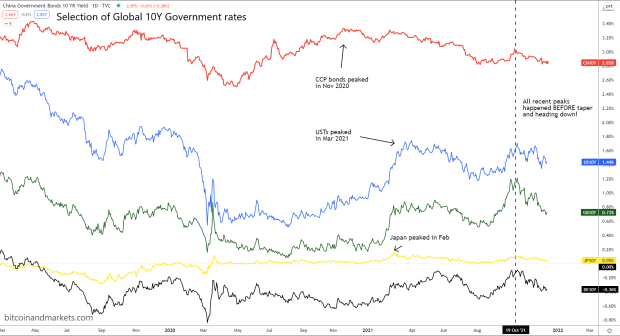

As an example of how the problems started long before the taper, here is a sample of the major 10-year bond rates around the world. If the economy is returning to normal or recovering, we’d expect rates to rise to normal. However, the majors peaked early this year, and everyone was heading down prior to the beginning of the taper.

Also, notice that rates have generally declined and tightened this year, in the midst of multi-decade high inflation.

What does the Fed wish to say with speeding up the taper?

It is telling people in the U.S. that their dollars are under threat of devaluation, so they should go out and spend. At the same time, it convinces foreign banks that the USD-denominated debt burden will lessen because the Fed is worried about losing control of inflation, so foreigners should go out and borrow and lend in USD.

The Fed is also hedging its bets. If recession comes, people won’t lose faith in the Fed’s monetary tools, but in its competence. It can handle investors thinking it made a mistake, but not that its tools don’t work.

This is a guest post by Ansel Lindner. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.