The Fed Must Have Confident Consumers

The Federal Reserve can’t let consumer confidence crumble.

I still remember the 2007-2008 financial crisis like it was yesterday. Leading up to the event, I read and listened to stories every day about the capital markets seizing up. Individuals were defaulting on home loans left and right. Bank balance sheets were ballooning with assets that were plummeting in value.

However, the mainstream media wasn’t running with the story as it first unfolded. So, the public wasn’t concerned. I can remember having a conversation with my in-laws about the topic over dinner. They couldn’t believe what I was discussing. Since they hadn’t seen or heard much about it on the television or radio, it wasn’t on the front of their minds.

Within a year, the stories were everywhere. As the carnage built, consumers panicked. You see, most people have the bulk of their net worth tied up in the value of their homes. As that started to fall apart, consumer confidence plummeted. Americans felt their net worth declining and started to pull back on spending.

:format(jpg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/coindesk/PFDENEGZTVEQ5KUHENBJFTCF6Y.png)

The officials who currently serve at the Fed all lived through this. Some, like Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari, were very involved in the bailout process. Others have helped to bring stability back to the financial system.

And most of them have served in their current positions through the COVID pandemic. They know what type of havoc the loss of consumer confidence can wreak on the economy. So, the last thing they want to do is see that happen again. That’s why the Fed just embarked on the current rate cut cycle and is likely to keep loosening for some time to come. The change should underpin a steady rally in risk assets like cryptocurrencies.

But don’t take my word for it, let’s look at what the data’s telling us.

In the early 2000s, the domestic housing market was on fire. Interest rates were low, and it was easy to borrow. Banks, looking to boost profits, were more than happy to lend the money. They could package the loans into collateralized obligations and make a killing on the associated margins.

As values kept rising, homeowners saw opportunities to borrow more money. Their houses were like ATMs. Banks kept making the loans to fuel growth, reaching further down the credit food chain.

Yet, all this borrowing led to spending, causing the economy to heat up. Inflation rose from 1.1% in mid-2002 to 3.3% by late 2004. Our central bank had to act. Between July 2004 and the same month in 2006, it raised the effective federal funds rate from 1% to 5.25%. And suddenly, buying houses just wasn’t as attractive.

:format(jpg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/coindesk/KSGGJR5NM5GXXFVMCEE6K2U33U.png)

Individuals had become overly leveraged against the value of their homes. They had borrowed more money than they could ever pay back. As house prices started to fall, loan-to-value ratios shot up. Homeowners soon realized it was easier to hand the keys back to the bank than it would be to spend the rest of their lives paying off the debt.

And that’s when consumer confidence began to collapse. If we go back to the chart at the beginning, we can see that according to the University of Michigan’s gauge, consumer confidence peaked at the beginning of 2007 at 96.9. At the time, borrowing costs were still high and the housing bubble was just starting to pop.

But then as people saw their life savings crumble in value, consumer confidence collapsed. It didn’t bottom out until November of 2008 at 55.3. In the meantime, the economy had cratered. The Fed had been slow to recognize the shift. It didn’t enact its first rate cut until late in 2007, well after house prices started to fall.

Eventually, our central bank would cut interest rates all the way back to zero. It would be another five years before consumer confidence saw a meaningful rebound and seven years before the Fed could raise rates again.

Fast forward to the pandemic and we see a similar story play out. State and local governments asked people to stay home for their safety. Schools and malls were closed while businesses asked employees to work remotely. No one knew how long it would last or what might happen to their income. Consumer confidence crumbled.

:format(jpg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/coindesk/ZEHEI3BI3RD3FMLBPOEOKJPPEM.png)

As you’ll notice in the chart above, the University of Michigan gauge peaked in February 2020 at 101. But two months later, it had tumbled all the way down to 71. It wasn’t until a couple of years later, in 2022, when individuals felt they could better navigate the post-pandemic world, that the consumer confidence gauge bottomed out around 50.

This time, like last, our central bank didn’t react until the crisis unfolded. By April 2020, it had cut rates to zero and was expanding the size of its balance sheet to inject money into the financial system. The Fed wanted businesses and individuals to spend. It was trying to boost confidence.

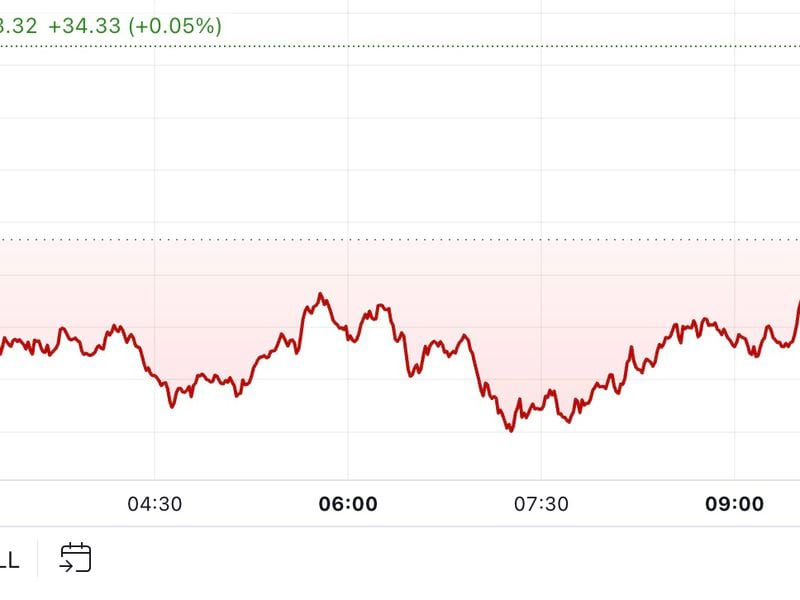

So now, let’s look at what’s going on with consumer confidence today:

:format(jpg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/coindesk/LGTRCTPGORDYHJCQNKTZISQNUE.png)

As you can see in the above chart, consumer confidence has been easing of late. Since peaking at 79 in March, it has dropped back to 66. Now this isn’t a cause for alarm, but it’s the most notable slide since the trough in June 2022. High interest rates are the probable cause. And the Fed has likely taken notice.

Living through a crisis is difficult to forget. The event typically involves some sort of life-changing difficulty for you or someone close to you. The event tends to shape the decisions you make, especially financially, going forward.

As I said at the start, most of the officials running our central bank were there during the pandemic and worked to rescue the financial system in the aftermath of the financial crisis. So, their thinking and actions on monetary policy are being shaped by these events.

As Bank of America CEO Brian Moynihan recently said, the consumer isn’t broken, but if the Fed doesn’t get going on rate cuts, it’s going to be a problem. The central bank can see the same signals in the system too. Policymakers know they can’t afford to lose consumer confidence: it will crush the economy and will take a long time to recover. So, rather than wait until something breaks, it’s attempting to get ahead of the problem.

The shift will lead to a series of rate cuts moving forward. That should underpin stable economic growth, improved consumer confidence, and a steady rally in risk assets like bitcoin and ethereum.

Note: The views expressed in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of CoinDesk, Inc. or its owners and affiliates.

Edited by Benjamin Schiller.