The Discovery Of Bitcoin Is A Piece Of A Puzzle

Bitcoin is a fundamental discovery in a long chain of cryptographic progress.

A recurring conversation in the Bitcoin community is the question “was Bitcoin invented or discovered?” Initially this question seems simple. Obviously Bitcoin was invented, wasn’t it?

No. In my opinion, Bitcoin, like any other scientific and technological “invention,” was discovered and not really invented.

The purpose of this article is to explain this and to help you understand why if Satoshi Nakamoto had never existed, Bitcoin would have eventually been discovered by someone else.

The Adjacent Possible

There is a figure in our collective unconscious showing the lone genius in his garage. This brilliant and misunderstood scientist is unraveling some of nature’s great mysteries all by himself.

This image is totally wrong. Even geniuses like Isaac Newton recognized that “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”

This concept seems counterintuitive at first, but historical evidence supports this view.

There are several scientific discoveries, such as calculus and the theory of natural selection, that have repeatedly occurred independently.

For most of us, the theory of natural selection is classically attributed to Charles Darwin. His story is well known: he sailed around the world on the HMS Beagle, studied finches in the Galapagos Islands, the 1835 earthquake in Chile, and so on. What few people know is that nowadays the authorship of the theory of natural selection is attributed to Darwin-Wallace.

That’s because it took Darwin more than 20 years to publish his discovery, and in the meantime a young naturalist named Alfred Russell Wallace reached the same conclusions that Darwin had reached. Wallace studied the Amazon rainforest and the Malay Archipelago. Were they two isolated geniuses who discovered how evolution works quite independently?

Yes and no.

These two brilliant scientists had access to the same references. Both cite the work of James Hutton and Charles Lyell, two geologists who discussed how changes occurred gradually over a large span of time, known as geological time or deep time. This view is known as uniformitarianism and is opposed to catastrophism, which at the time was associated with the Great Flood and the idea that the Earth’s age was only 10,000 years. Thanks to these authors, the concept of deep time began to exist in the scientific community. Both Darwin and Wallace read these works.

The same goes for the work of Thomas R. Malthus. Malthus discussed the issue of finite resources and even sketched out ideas of “fight for life” and “survival of the fittest.” But he focused his work on population geography, not nature more broadly. Both Darwin and Wallace quoted Malthus’ work as a key piece in the evolutionary puzzle.

The same goes for Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who independently discovered calculus. Those mathematicians spent the rest of their lives struggling to establish who was the real inventor of calculus rather than considering that it could be developed twice in a short time.

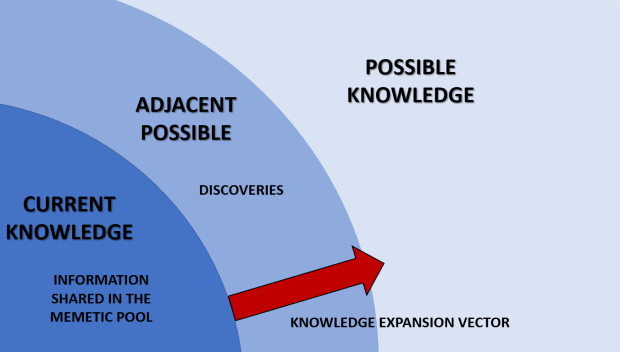

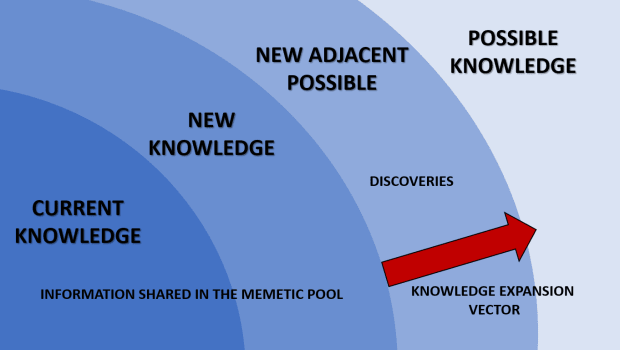

The term “adjacent possible” was coined in 1996 by Stuart Kauffman, an evolutionary biologist. For him, biological systems are capable of transforming into complex systems from incremental changes. This helps explain how complex systems originate: one step at a time.

For example: the origin of life hypothetically occurred in a primitive environment known as “primordial soup.” The atmosphere lacked oxygen, and was rich in hydrogen, ammonia, methane and water. Something caused these molecules to stick together and become amino acids. These were able to combine to form proteins and create organic material. This organic material may have eventually given rise to biological life as we know it today. Each step in this chain could not have existed before the previous step. Hydrogen, methane, water and ammonium wouldn’t bond together to form proteins, but their recombined form called amino acids would.

The adjacent possible is the essence of the scientific process, when new knowledge is discovered based on the available adjacent knowledge, whether books or scientific articles. Basically, existing scientific knowledge represents the pieces of a puzzle already assembled in front of everyone. The scientist who makes a discovery simply finds the fit of the most recently fitted piece.

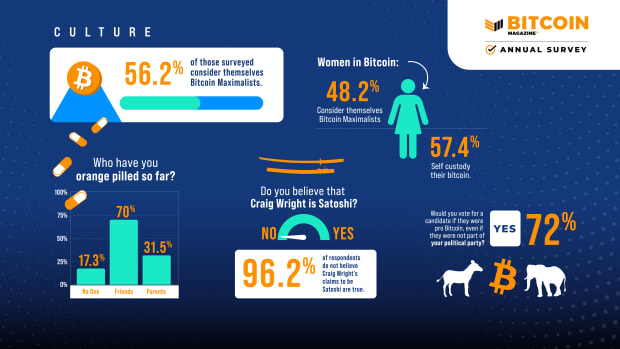

The original concept of “meme” was defined by biologist Richard Dawkins in the book “The Selfish Gene.” This book is a study of how genes are the unit of selection in evolution, not the species, group, or even the individual. In the book, the author proposes that genes are to biology what memes are to cultural information, and the smallest unit of cultural selection is a meme. In other words, both a story, a song and even an image with text on top are memes. Analogous to the “gene pool,” there is a “meme pool,” where all memes compete for space, are shared or forgotten. These cultural units are in a meme pool, where all scientists can consult the information.

This meme pool is shared and makes the possibilities for scientific and cultural evolution limited to the adjacent possible that these units of cultural information allow. In other words, it would not be possible to have a theory of natural selection without Malthusianism or uniformitarianism.

The fictional science of psychohistory, described by Isaac Asimov, illustrates this concept well. In psychohistory, even if the actions of a particular individual cannot be predicted, future events can be predicted using statistics applied to large populations.

Both psychohistory, a concept from science fiction, and the adjacent possible, a concept from biology, have a common characteristic: the actions of specific individuals do not matter for the macro tendency.

We like to think of ourselves as special snowflakes, but actually we’re all quite commonplace with limited basic variations and a few possible personality archetypes, as the few categories in any personality test like the Holland Code (RIASEC) or Myers-Briggs tests demonstrate.

Which raises the question: can a human being invent something really new?

The Discovery of Bitcoin

“Privacy is necessary for an open society in the electronic age.” – Eric Hughes, Cypherpunk Manifesto, 1993

As with the image of the lone scientist, we also tend to imagine Satoshi Nakamoto in this way. But in reality, he was also on the shoulder of giants when he conceived Bitcoin.

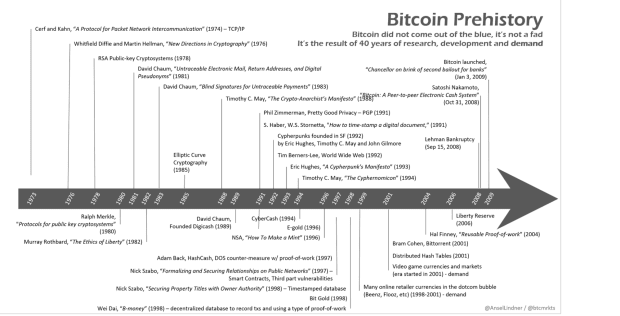

Bitcoin may seem “new,” but in reality it is the culmination of a 30+ year process by a group of people interested in encryption and privacy. They are called “the cypherpunks.” The Cypherpunk Manifesto dates back to 1993; several attempts to resolve the issue of conveying value with privacy without the need for a trusted external validator had already been made and failed. In a nutshell, we can simplify some of the puzzle pieces of the cypherpunk memetic pool used by Satoshi:

- In 1997, Adam Back created Hashcash, an anti-spam instrument that made it costly (in time and computing power) to send an email, making spam economically unfeasible.

- In 2004, Hal Finney created the reusable proof-of-work (RPOW) based on Hashcash. RPOW were cryptographic tokens that could only be used once. Validation and double-spend protection was still performed on a central server.

- In 2005, Nick Szabo published the proposal for “bitgold,” a digital token based on RPOW. Bitgold did not have a token limit, but imagined that the units would be valued differently according to the amount of computational processing used in their creation.

- In 2008, a person operating under the pseudonym of Satoshi Nakamoto published the Bitcoin whitepaper, which directly cites both bitgold and Hashcash.

It was by learning from all these attempts that Satoshi was able to reach the magical possible adjacent called Bitcoin. But the truth is that, as brilliant as Satoshi was, if he hadn’t discovered Bitcoin in 2008, someone would have probably already discovered it by now.

This is a guest post by Leta. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.