The Conclusion Of The Long-Term Debt Cycle And The Rise Of Bitcoin

The conclusion of the long-term debt cycle is an inescapable economic reality that coincides with the ascent of the Bitcoin Network.

In this article, I will detail why the incumbent global financial system is irreversibly broken, how it got to this point, and what the world will look like coming out the other side of the present crisis. I will use the frameworks presented in Ray Dalio’s Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises along with my own analysis to contextualize the global economic landscape, and I will detail how the emergence of bitcoin as a global monetary asset will serve as a release valve.

For an abridged version of Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises, watch this excellent 30-minute video produced by Dalio himself.

The Cyclicity Of Debt

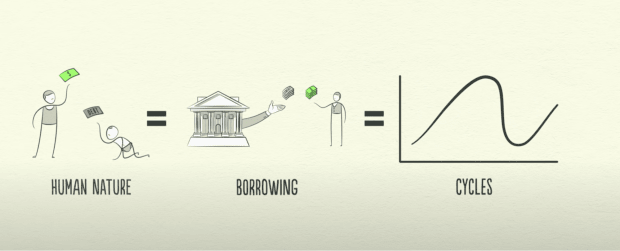

To put it simply, debt is cyclical. When you borrow money today, you increase your buying power today at the expense of the buying power of your future self. Buying something you cannot afford today means that you are spending more than you make: you are borrowing not only from the lender but also from your future productivity/output. In an economic system built on credit, expansions and contractions of credit availability serve as drivers of economic growth/activity and contraction/recessions, respectively.

This holds true at both the individual and macroeconomic levels. When an individual borrows money to consume or invest and does not receive a positive return, it decreases that person’s future investment/consumption/spending. The same framework applies to sectors of an economic system, or more broadly, economic systems as a whole.

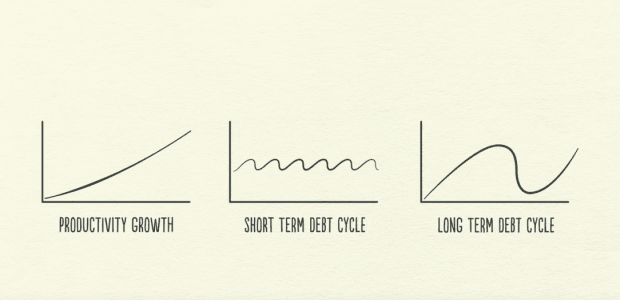

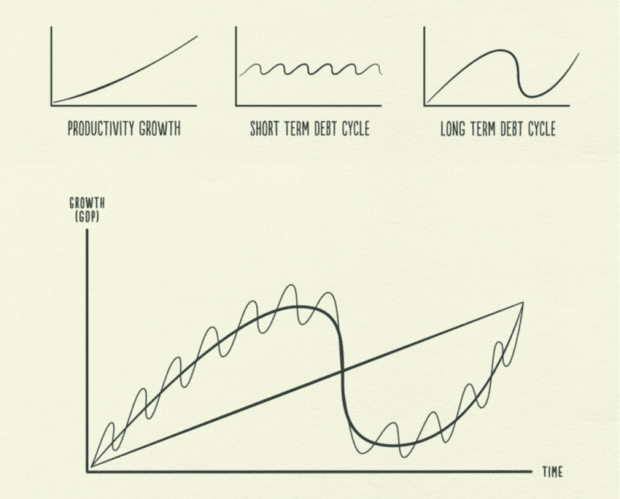

Although productivity is the most important aspect of an economic system over the long term, not productivity but the forces of debt/credit are the main driving forces in volatile economic swings.

Time Value Of Money

The time value of money is a very important concept in the roles of debt and credit in an economic system. Explained simply, any rational economic actor would prefer to receive money today rather than the same amount of money in the future. There is an opportunity cost to parting with money, and the return that one could earn on their money tomorrow by parting with it today should theoretically be positive to compensate for risk and opportunity cost.

The Interplay Between The Short- And Long-Term Debt Cycles

Although most are familiar with the short-term debt cycle, many are unfamiliar with the concept of the long-term debt cycle, which is of much greater significance. The reason why many are unfamiliar with the long-term debt cycle is because it repeats very rarely, about once every 75–100 years. Most people live their entire lives without experiencing the conclusion of a long-term debt cycle, and thus, its significance is rarely understood.

Below, I will outline the archetypal short- and long-term debt cycles and present some historical context and current statistics to frame the current state of the domestic and global economy.

The Short-Term Debt Cycle: ~7–10 years

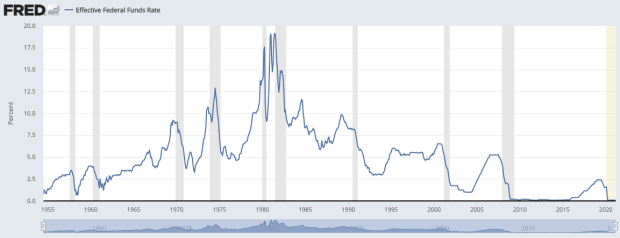

Debt cycles can be observed by viewing debt-to-income ratios and interest rates, among other metrics. Although there has not been a completely free market for the cost of capital during the era of central banking, interest rates set by central banks serve as the “risk-free rate,” upon which the economic foundation is built. With the advantage of hindsight, one can clearly see many examples of short-term debt cycles, more commonly known as the “boom-and-bust cycle,” by looking at the interest rates set by central banks.

The Long-Term Debt Cycle: ~75–100 years

The long-term debt cycle is made up of numerous short-term debt cycles. Debt crises occur because debt and debt servicing costs rise more rapidly than incomes are able to support them, which necessitates deleveraging. In response to credit contraction, central banks can lower interest rates, which reduces relative debt servicing costs and provides the economy with a stimulative boost. This process repeats itself as productive investments are made, and the self-reinforcing upward boom of credit expansion then brings about speculative activity and misallocation of capital. Eventually, the debt burden and interest expenses grow far too large to service, and central banks respond by again cutting interest rates.

Over the course of each cycle, interest rates at the cyclical peak and trough are lower than those at the peak and trough of the previous cycle. This process repeats until the interest rate reductions that enabled each subsequent expansion can no longer continue, as interest rates reach the lower bound of zero. Interest rates hitting zero marks the beginning of the end for a currency regime, as it signifies that debt loads across the economic system have reached unsustainable levels. The logical path from that point, if we follow policy makers’ incentive structure with a historical perspective, is to sacrifice the value of the currency.

Types Of Monetary Policy

In a deleveraging event, three main forms of monetary policy can be used to ease the debt burden. As defined by Dalio in Big Debt Crises:

Monetary Policy 1: Interest rate-driven monetary policy. This is the go-to tool used by central banks and is the most effective tool to “stimulate” the economy. This is because lowering rates

1) raises the present value of assets, 2) makes it easier to buy items and invest with credit, and 3) reduces the debt-servicing burden. Interest-rate reduction is almost always the first response to a debt crisis, if there is room to cut the rates any further.

Monetary Policy 2: Quantitative easing (QE), or “printing money” to buy debt securities/financial assets. QE places cash in the hands of investors, who then seek to redeploy it into other financial instruments. Some economists argue that QE is not money printing money because simply entails swapping out a financial asset. This logic is flawed, as the freshly printed cash places bids in the credit markets that would not have otherwise existed.

QE positively affects investors and asset values but does very little to help those without assets. In many cases, including the present-day situation, this widens the wealth gap significantly. The more that QE is used, the less effective it becomes. QE is the most effective when there is a lack of liquidity in financial markets, but once credit markets become sufficiently reinflated, the effects diminish with each marginal unit of currency that is printed.

Monetary Policy 3: “Stimulus payments.” This form of policy puts money directly in the hands of the people. The recent popularization and support for universal basic income and stimulus checks are examples of Monetary Policy 3. This form of monetary policy is used because the first two forms disproportionately benefit the investor class, leaving the middle and lower classes struggling to get by. Political acceptance of this type of monetary policy becomes most prevalent late in a debt cycle, when wealth gaps are the most severe and the masses are looking for any possible way to “get ahead.”

Another form of this type of monetary policy is debt-financed fiscal spending monetized by the central bank, or what is today being called “Modern Monetary Theory.”

Brief Overview Of Monetary History

The dollar and the global monetary order changed considerably in 1971 with the Nixon Shock. With other nations having previously agreed to peg their currencies to the US dollar, and the US dollar redeemable for gold by global central banks, the decision by Nixon to “temporarily” close the gold window in August 1971 changed the global monetary order forever. Shortly following this decision, in March 1973, the currencies of the G10 nations abandoned the fixed exchange rate standard and began to float in the open market.

For the first time in history, nearly the entire world—with an increasingly developed and interconnected global economy—had free-floating (i.e., purely fiat) currencies. As a result, a very interesting dynamic has become increasingly prevalent whereby nations are incentivized to competitively devalue their currencies (and thus the cost of capital within their domestic economies) to attract foreign capital inflows and boost their export markets.

If a nation maintains the strength of its currency and does not devalue it along with the rest of the world’s fiat currencies, the country’s buying power appreciates significantly, but its domestic manufacturing base and competitiveness in international trade diminish significantly.

Although the dollar and the monetary policy decisions of the Federal Reserve are domestic, the decisions made by policy makers do not exist in a vacuum and are influenced by the dollar’s role as the international economy’s global reserve currency.

The Endgame

It is clear that we are in the final stages of a debt supercycle that has played out over the last ~80 years. We are in the endgame of the current monetary order, and something new will have to fill the void.

Over the last 4 decades, interest rates have been in a secular downtrend, and conversely, debt loads have continued to pile up across the economic system. Every economic boom that has occurred since 1981 has been aided by stimulus in the form of looser monetary policy.

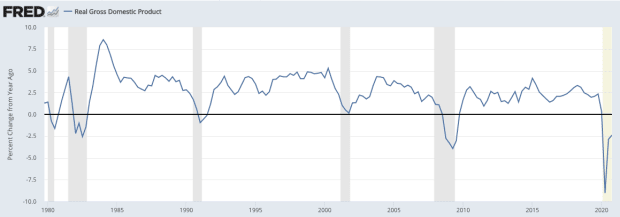

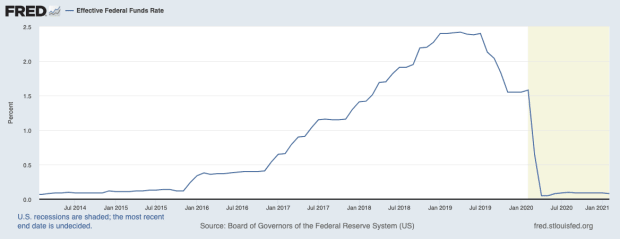

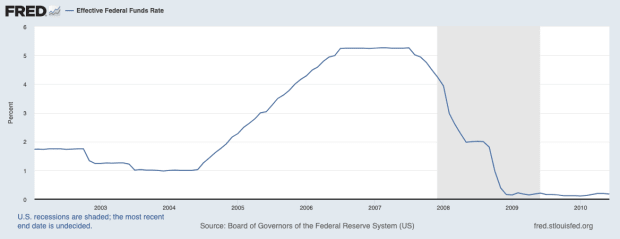

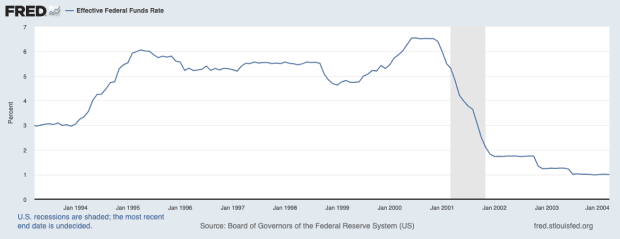

This can be observed in a chart of the Effective Federal Funds Rate as well as the y/y percentage change in real GDP. Long-term growth in productivity and technology result from human entrepreneurship and ingenuity, but over the short–medium term, credit cycles have important impacts on economic activity.

Note the reduction of interest rates that follows every decline in real GDP.

Interest rates peaked at 19% in 1981, and over the last 40 years, they have been in a secular downtrend. In other words, for the last 40 years, the discounted cash flows have caused every asset to skyrocket. Bonds, equities, and real estate have all appreciated by orders of magnitude based on the valuations supported by ever-decreasing interest rates, and these price increases cannot be effectively measured with the flawed CPI metric. Now, with the Federal Reserve’s funding rates at the zero lower bound, reducing interest rates is no longer an option.

Below are charts that illustrate three of the latest short-term debt cycles, as observed by the Effective Federal Funds Rate.

Second-Order Effects Of Easy Monetary Policy

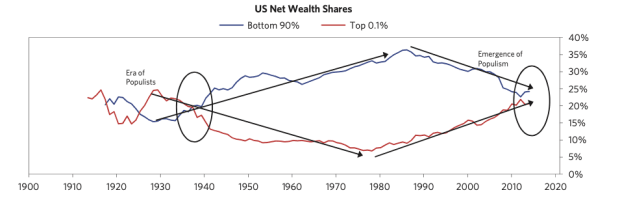

A side effect of the increasingly easy monetary policy over the past decades has been significant asset price inflation. The majority of the increase in asset prices has not been the result of increased productivity or output, but rather the result of massive credit expansion and lessening discount rates following each subsequent “bust” or deleveraging event. Asset price inflation concentrates wealth into the hands of the few, and social unrest and popular polarization are second-order effects of this.

“Wealth gaps increase during bubbles, and they become particularly galling for the less privileged during hard times… It is during such times that populism on both the left and the right tends to emerge. How well the people and the political system handle this is key to how well the economy and the society weather the period. As shown below, both inequality and populism are on the rise in the US today, much as they were in the 1930s. In both cases, the net worth of the top 0.1 percent of the population equaled approximately that of the bottom 90 percent combined.” – Big Debt Crises

With this framing, the polarization and political division that have emerged in the United States over the last decade make sense. There is nothing new under the sun, and if we turn back time, we can view similar instances throughout history. The increasingly popular populist movements and policies that have taken hold in the United States are an expected response from a class of people who have been hurt by monetary policy decisions that have spanned across decades. Anyone focusing on the individual actors and not the systematic inequality created and enabled by easy money monetary policy is missing what has truly taken place.

“In some cases, raising taxes on the rich becomes politically attractive because the rich made a lot of money in the boom—especially those working in the financial sector—and are perceived to have caused the problems because of their greed. The central bank’s purchases of financial assets also disproportionately benefit the rich because the rich own many more such assets. Big political shifts to the left typically hasten redistributive efforts. This typically drives the rich to try to move their money in ways and to places that provide protection, which itself has effects on asset and currency markets.” – Big Debt Crises

A recent example can be seen in the push by Democratic Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders to pass a wealth tax. Different from a standard capital gains tax, a wealth tax would confiscate a percentage of one’s wealth above a certain net worth threshold. Many people across the political spectrum believe that these policies are needed because of the “ills of capitalism” However, the irony is that the massive economic imbalance and wealth inequality currently present in the United States (and worldwide) are not the results of free market capitalism. The large proportion of wealth held by the 1% and the investor class is not the result of productivity gains, but rather financial engineering enabled by easy monetary policy.

“Free-Market Capitalism?” Not So Fast…

Although the United States is frequently described as being “free-market capitalist,” this statement is not exactly true. Here is why:

In a free-market capitalist economic system, the most important pricing mechanism is that of money. When there is a monopolist institution setting the price of money, the market is inherently not “free.” There is nothing free about reducing the price of money whenever there is an economic downturn, including the most recent injections of hundreds of billions and now trillions of dollars into financial markets whenever a major liquidation of malinvestment occurs. This monopolistic pricing of money has partially enabled past systemic crises and will ensure the growth of future imbalance and excess. This is what has enabled the gross misallocation of capital, the effects of which are most glaringly obvious in the negative real interest rates offered in sovereign debt markets.

Time Value Of Money = Negative?

With the Federal Reserve pegging interest rates at zero, along with conducting massive QE programs to monetize federal deficits, the underlying “risk-free rates” of the financial system actually promise return-free risk. As a result, asset valuations have soared, and the holders of said assets have gotten exponentially more wealthy.

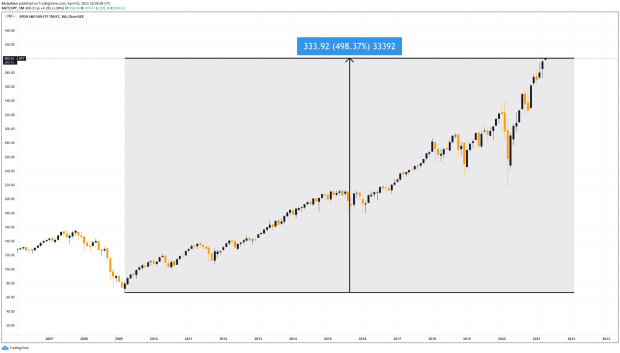

The wealth divide has been further exacerbated since the 2008 financial crisis. Below is the S&P 500 Index, which has risen nearly 500% in just 12 years, fueled by the ZIRP (zero interest rate policy) and QE.

A recent study by the Federal Reserve Board’s Survey of Consumer Finances found that the top 10% of U.S. households owned 84% of all U.S. equities, whereas the bottom 50% of households held just 1%. This alone establishes that when Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell states that Fed policies “absolutely don’t contribute to wealth inequality,” he is flat-out lying to save face, full stop.

What Comes Next?

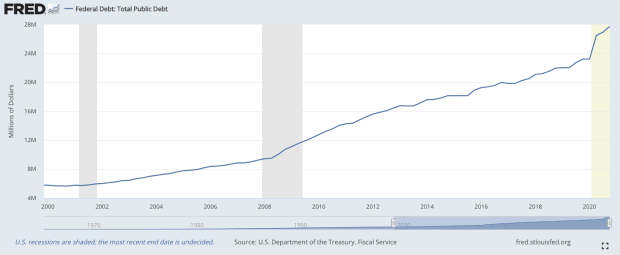

So, what happens next? The gap between the “haves” and “have-nots” has never been wider, central banks have been promising to keep interest rates at 0% for quite some time, and debt loads across the entire economy are larger and more unsustainable than ever before.

There is mathematically no way out of the current economic environment. The only path forward that policy makers know is more of what caused the problems in the first place: More stimulus in the form of QE (to provide financial markets with additional liquidity and suppress yields) and fiscal stimulus in the form of direct checks and aid to the people to minimize unrest.

This is not a sustainable system, as it is supported by exponentially expanding the monetary base, which simply exacerbates the problems of the current economic environment. In this reality, asset prices will continue to go parabolic, and it will become increasingly hard to get by for the lower and middle classes as real wages decrease due to monetary policy coupled with technological advancement stripping away automatable jobs that were previously performed by humans. The current actions being taken are simply not a long-term solution, as a look at the empirical data shows.

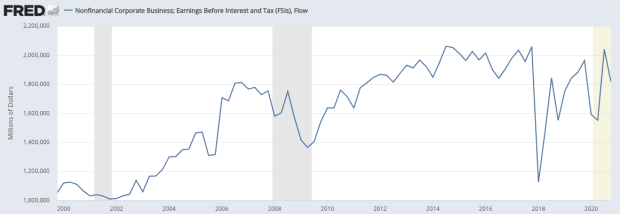

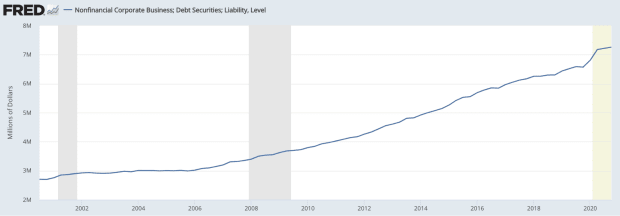

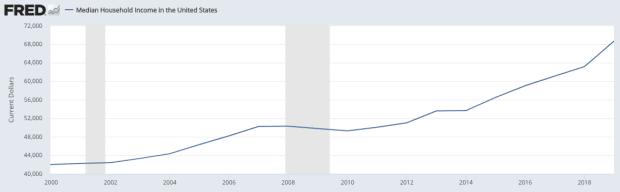

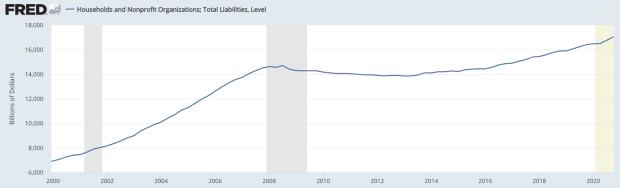

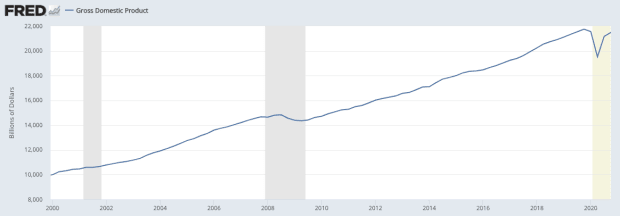

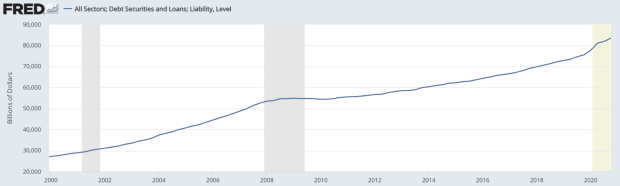

Displayed below is a series of charts that show various debt and income metrics since 2000. Feel free to draw your own conclusions from them.

Technology Changing The Rules

The problem with chasing perpetual “growth” fueled by ever-increasing credit expansion is that the rules of the game have changed. Technology has fundamentally changed the rules of our economic system, and our monetary system is unable to adjust.

We live in a world where rapidly improving and advancing technology continues to give us more for less. As jobs of the past are automated away, and technology continues to drive the costs of many aspects of life to near zero, our monetary system necessitates that everything continue to increase in cost in nominal terms in perpetuity. Even though technological advances should be giving everyone the gift of a higher standard of living for less real cost, the incumbent monetary system must avoid deflation at all costs.

In a world that is experiencing exponential technological growth, exponentially more stimulus and debt are needed to keep the system glued together. Without ever-increasing amounts of stimulus in the form of central bank balance sheet expansion, the debt loads that have built up over the last 40 years would unwind, the cost of debt would explode in real terms, all of the banks would become insolvent, and the global economic system would experience a massive depression. Remember, it is only possible to consume more than you produce for so long, at both the microeconomic and macroeconomic levels.

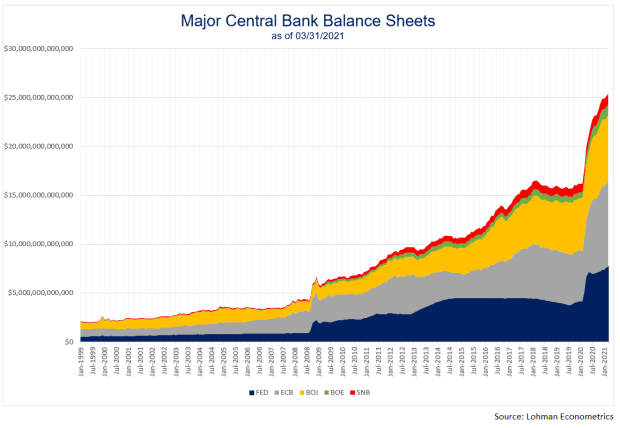

Shown below are the balance sheets of the world’s major central banks. Although this piece has focused on the U.S. domestic economy, this figure shows that we have been describing a global phenomenon.

Policymakers are trapped by decisions made decades before their tenures. Their actions make sense with this framing, but that does not make said actions “right” or a practical long-term solution for the global monetary and economic system.

Human civilization is at an inflection point. Inflationary monetary policy against the backdrop of technological deflation means either that ever more power will become concentrated in the hands of the state, or that one by one, individuals will voluntarily opt into and adopt a superior monetary system, the rules of which cannot be arbitrarily changed.

The Solution: Bitcoin

“At this stage [in the long term debt cycle], policy makers sometimes monetize debt in even larger quantities in an attempt to compensate for its declining effectiveness. While this can help for a bit, there is a real risk that prolonged monetization will lead people to question the currency’s suitability as a store hold of value. This can lead them to start moving to alternative currencies, such as gold. The fundamental economic challenge most economies have in this phase is that the claims on purchasing power are greater than the abilities to meet them.” – Big Debt Crises

We are seeing this play out today. The global economic system is so over-indebted that there would be a deflationary collapse without ever-increasing liquidity injections/stimulus. As a result of rates being stuck at the zero lower bound and exponentially increasing debt monetization, a mass default is occurring not explicitly but implicitly. The error term is the value of the currency itself, which in this case is the dollar. A debt jubilee is coming in the form of creditors having their purchasing power wiped out.

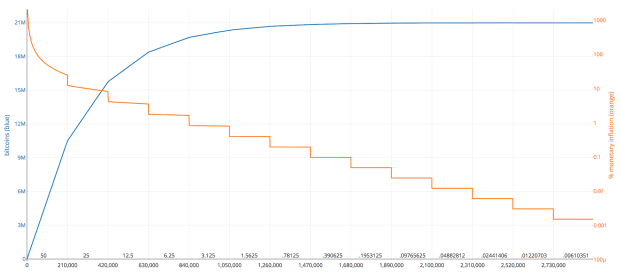

During a period of debt monetization, the rational economic incentive is to protect one’s wealth by seeking out assets that cannot be devalued or “printed,” like bitcoin. There will only ever be 21,000,000 bitcoin. With its perfectly inelastic, programmatic supply issuance, it is the logical choice for every rational economic actor to adopt as a primary store of value, medium of exchange, and eventually unit of account for all economic calculations.

“Quite often, they are motivated to move their money out of the country (which contributes to currency weakness), dodge taxes, and seek safety in liquid, noncredit-dependent investments (e.g., low-risk government bonds, gold, or cash)… This typically drives the rich to try to move their money in ways and to places that provide protection, which itself has effects on asset and currency markets.” – Big Debt Crises

As previously mentioned, wealth taxes and increasingly ambitious taxation methods are being floated around the political sphere as “solutions” to the record wealth gap. History and economic reality tell a different story: these taxes are rarely effective, as the wealthy find a way to move their wealth outside of the taxable domain. Now, with the emergence of bitcoin, there is a seizure- and censorship-resistant asset that is outside the domain of any one jurisdiction. With Bitcoin, it is possible to store wealth in a self-sovereign way with absolutely zero counterparty or credit risk. Any individual or entity facing unfavorable tax codes can simply protect their wealth behind a wall of encrypted energy, free from the state’s needy hands.

The incumbent monetary order is irreversibly broken. In a process that has unfolded over nearly a century, the monetary system of the United States and the world has changed, and a small class of people have benefited at everyone else’s expense. If you are pro-humanity, then you must agree that a system of rules is superior to a system of rulers. Against the backdrop of technological advancement, a compatible monetary system is needed. Money is the coordination function of every action in the economy, and Bitcoin is the best tool humanity has ever had at its disposal to harness this function. With Bitcoin, money is once again a free-market phenomenon, and humanity will flourish as a result.

For 12 years, Bitcoin has entrenched itself worldwide as an alternative monetary system that individuals are free to voluntarily adopt. Despite neverending streams of denouncement from “economic experts” and “monetary authorities,” bitcoin continues to exponentially increase in value.

Now, with the incumbent monetary order cannibalizing itself, here stands Bitcoin, a digital monetary network that provides direct incentives for every individual and entity on the planet to adopt it.

A great debt jubilee is coming, and it will later be known as hyperbitcoinizaiton.