SNICKER: How Alice and Bob Can Mix Bitcoin With No Interaction

SNICKER could be the next tool in Bitcoin’s growing privacy toolbox.

Although Satoshi Nakamoto’s white paper suggests that privacy was a design goal of the Bitcoin protocol, blockchain analysis can often break users’ privacy today. This is a problem. Bitcoin users might not necessarily want the world to know where they spend their money, what they earn or how much they own, while businesses may not want to leak transaction details to competitors — to list a few examples.

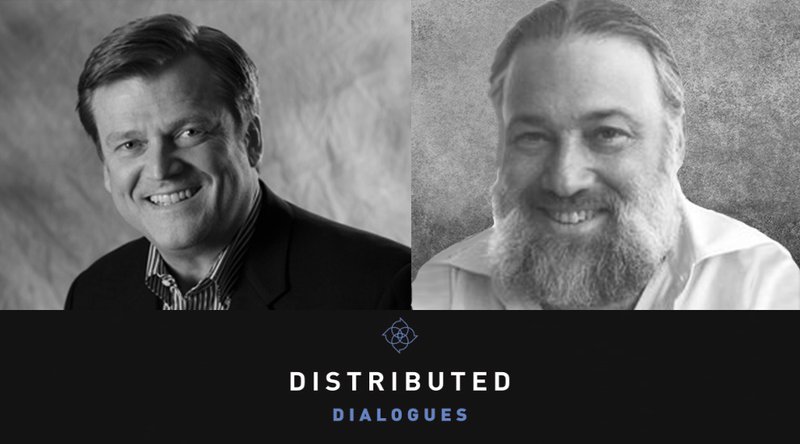

Fortunately, Bitcoin developers and researchers are coming up with more and more solutions for users to reclaim their privacy. One of these champions for Bitcoin privacy is Adam “waxwing” Gibson, perhaps best known for his contributions to JoinMarket, a protocol that lets users mix their coins — and offers a financial reward for participating in such mixes.

More recently, Gibson presented a new idea: SNICKER (Simple Non-Interactive Coinjoin with Keys for Encryption Reused). Now submitted as a draft Bitcoin Improvement Proposal (BIP), SNICKER would allow for coin mixing without any synchronization or interaction: There’d be no need for users to coordinate or be online at the same time.

CoinJoin

SNICKER is based on the, by now, well-established, bitcoin mixing technique CoinJoin. Some of the most popular mixing solutions available today already use this trick, including Wasabi Wallet (ZeroLink), Samourai Wallet (Whirlpool) and JoinMarket.

Further Reading: What Are Bitcoin Mixers?

CoinJoin is essentially a tool to merge several transactions into one. So let’s say Alice wants to pay Carol one bitcoin, and Bob wants to pay Dave one bitcoin. In this example, Alice and Bob can cooperate to create one big transaction, where both spend one bitcoin (two total), and Carol and Dave each receive one bitcoin. A blockchain spy will not be able to tell which of the senders paid which of the recipients, benefiting the privacy of all.

In reality, however, the amounts of bitcoin transacted are often privacy leaks. If Alice wants to pay Carol one bitcoin, but Bob wants to pay Dave two bitcoin, it will be obvious who paid who by matching the sending and receiving amounts.

That’s why CoinJoin is more typically used for mixing. Instead of paying someone else, Alice and Bob both send one bitcoin to themselves. By merging this in one transaction, blockchain spies can’t tell who got which coin back: The coins are mixed, protecting both Alice and Bob’s privacy going forward.

CoinJoin mixers work today, but they have a drawback: They require interactivity. A CoinJoin transaction is only valid if all participating users sign the whole transaction — but to sign the whole transaction, participating users must have first added all of their coins and new receiving addresses to it. This typically means that they need to pass the transaction around a few times and usually requires them all to be online at the same time.

Such requirements are a bit of a hurdle for many users, which is one reason CoinJoin transactions aren’t very common. These requirements are what SNICKER gets around.

SNICKER Version 1

The protocol described in this section is the first proposed version of SNICKER. This version is slightly easier to understand than alternative versions but it is important to note that it’s actually not the best version of the protocol, or the version that is most likely to be implemented. (More on alternative versions later.)

With that said, here’s how SNICKER version 1 works:

Say Alice has one bitcoin she wants to mix, represented by an unspent transaction output (UTXO) on the blockchain. The first thing she does is to resend this bitcoin … to her same address. That’s right, in this version of SNICKER, she’s reusing an address, which violates Bitcoin’s best practices. But it comes in handy: It publicly marks the UTXO as (potentially) available for mixing.

This doesn’t mean Alice can’t use the coin, by the way. It’s still sitting in her wallet, ready to be spent at any time. It’s just marked, in case anyone cares.

Bob also has one coin to mix. (In actuality, the amounts don’t need to be equal beforehand — Bob just needs to have at least as much as Alice.) Bob doesn’t know Alice, but he does know that users like Alice are out there, marking their UTXOs as mixable. So Bob scans the blockchain for potential matches. He finds Alice’s UTXO, and probably some more matching UTXOs, including false positives (not all reused addresses are really available for mixing). But let’s, for now, for simplicity, assume Bob only finds one match: Alice’s UTXO. (We’ll get back to the other potential matches and false positives later.)

With the match, Bob now takes the public key corresponding to the reused address. This is possible exactly because the address is reused: By spending it the first time, Alice published that public key on the blockchain. (Public keys become visible on the blockchain once the coins are spent, whereas addresses are always visible.)

At this point, Bob has Alice’s UTXO (because she marked it) and her public key (because she spent from her address once).

Now, Bob uses Alice’s public key and combines it with his own private key (for the coin he wants to mix) to create a “shared secret.” Quite literally the oldest trick in the cryptography book, this secret is shared because only Alice and Bob can generate it: Bob with his private key and Alice’s public key, and Alice with her private key and Bob’s public key (corresponding to the coins he wants to mix).

So now, Bob has Alice’s UTXO and her public key, and a shared secret (because he generated it with Alice’s public key and his private key).

Bob uses the shared secret in a novel way. He uses it to mathematically “tweak” Alice’s public key. This tweaking actually creates a new public key. Except … no one has the private key for it. Yet.

Interestingly, thanks to another bit of crypto magic, the tweaked private key for the tweaked public key can be discovered by Alice as well! If she’d tweak her original private key with the same shared secret, the resulting tweaked private key would correspond to the tweaked public key.

In other words, Bob can generate a new public key and therefore a new Bitcoin address for Alice, that only she can spend from. Even without her knowing right now!

So, Bob now has Alice’s UTXO and her public key, a shared secret, and a new Bitcoin address for Alice (generated with her public key and the shared secret).

This is nearly enough to create a valid CoinJoin transaction. Specifically, Bob takes Alice’s UTXO and adds the UTXO for his own coin, so there are two inputs. He then adds Alice’s new address and an address of his own as outputs (as well as fees and some other details, like a change address for himself, if needed). And he signs the transaction.

The only thing missing now is Alice’s signature.

Reaching Alice

The final step — reaching Alice — is actually easier than it sounds but requires one last trick.

Bob could simply publish the almost-complete CoinJoin transaction somewhere for Alice to find. For example, on a bulletin board dedicated to SNICKER users; preferably one on a Tor hidden service or otherwise guaranteed to offer anonymity of publishers.

However, if done in plain text, this would still not be ideal. If a spy keeps an eye on the bulletin board, they could trivially see which input belongs to the proposer (in this case Bob), and which input belongs to the taker (in this case Alice): The signed one is the proposer’s. This could be a privacy leak in itself. But it’d be even worse if Bob makes more proposals to mix different coins. In that case, the spy might be able to connect all of the different UTXOs to Bob, for example, because his batch of proposals was posted to the bulletin board at the same time.

So, instead, Bob encrypts the CoinJoin transaction … with Alice’s public key! That way, only Alice can decrypt the transaction and the spy cannot learn anything.

After posting the encrypted transaction on the bulletin board, Bob has done all he needs to do. He can disappear online, if he so pleases.

Alice’s Turn

As the CoinJoin transaction is now encrypted, this does introduce one last, slight complication. While Alice knows where to look for the package — on the SNICKER bulletin board — she doesn’t know what to look for: All CoinJoin transactions on the bulletin board look like encrypted blobs.

There is only one way out. Alice needs to try and decrypt all packages with her private key, hoping that one of them turns into something useful.

But when Bob’s encrypted blob turns into a CoinJoin transaction, Alice has everything she needs to complete the mix. She uses her private key and Bob’s public key (which is included in his input) to generate the shared secret, which she can, in turn, use to create her new, tweaked private key. After checking that the new key corresponds to her new receiving address in the output, she signs and broadcasts the transaction to the Bitcoin network.

Alice and Bob mixed their coins, even though they never interacted, nor did they even need to be online at the same time.

And while the process may sound somewhat laborious in text, keep in mind that all of it can be abstracted away by software, to be translated into a few buttons on a laptop or phone screen, or even automated completely.

SNICKER Version 2

SNICKER as explained so far, is the first version of the proposal. Already, Gibson has suggested a second version, and other variations are on the table as well.

The second SNICKER version is similar but avoids the need for address reuse — at the cost of slightly more complexity.

In this second version, Bob does not get Alice’s public key from a reused address. Instead, Bob takes the public key from an input of the same transaction that created Alice’s UTXO. Bob assumes that at least one of the inputs in that transaction was created by Alice herself and that she still has the private keys for these.

Bob makes this assumption because this time, Alice’s UTXO is even more clearly marked as available for mixing, and it would only be so clearly marked if Alice controls the private keys corresponding to the inputs. The SNICKER BIP does not specify how the initial marking would be done but suggests that certain wallets (like JoinMarket wallets) unmistakably reveal such information. Alternatively, Alice could simply post a message on the bulletin board advertising her UTXO.

But even better: Once SNICKER starts being used, finding new matches should become much easier. This is because SNICKER transactions themselves would be trivial to recognize, and existing SNICKER users are likely to want to mix their coins again. In other words, after an initial bootstrapping phase, unmixed coins would be mixed with previously mixed coins, resulting in more mixed coins which could in turn be leveraged for more mixing.

Challenges and Opportunities

As mentioned above, the SNICKER BIP is still just a draft and subject to review and potential improvement. (Already, the idea has evolved in some aspects since it was first publicly proposed by Gibson in a blog post.) The proposal has now been submitted to become a BIP so it can be standardized and, down the line, be made compatible between different wallets.

SNICKER is also faced with some open questions and challenges, although none of these seem insurmountable. These include, for example, which UTXOs should be selected as matches, and, in particular, how to limit the number of false positives. Besides reused addresses, potential matches could for example be filtered for amounts, age of the UTXO or specific types of wallets used.

But as alluded to earlier in this article, even if there are multiple matches (including false positives), this is likely only a small problem. Offerers (“Bob”) could simply create candidate transactions for all of them. Even if these proposals conflict (because Bob uses his same UTXO for all), it simply means that the first taker (the first “Alice”) to respond will get the mix — other potential takers will find they were too late, but no harm would be done. For false positives, no real harm is done either, Bob’s offer will just sit on the bulletin board, ignored forever (or until it’s removed).

What could be a particularly significant problem, however, is spam. Because the bulletin board would host encrypted blops of data, it would be impossible to filter out “fake” proposals: random gibberish posted by an attacker to disrupt the SNICKER protocol. Gibson proposed some solutions to this problem in his draft BIP, but these would present new trade-offs, like a cost to post a proposal.

On the flipside, SNICKER also offers some benefits that have been left out of the explanation so far for the sake of simplicity. One such benefit is that offerers) can add some funds to a taker’s output, adding some financial incentive to accept the mix. It may also be possible to conduct SNICKER mixes with more than two users at the same time — although this will make the trick much more complex.

And exactly because the protocol is noninteractive, Gibson believes that SNICKER would be relatively easy to implement in wallets, compared to some other privacy technologies, like JoinMarket. So far, the Electrum wallet has shown interest in adopting the proposal — though actual implementation of it may still be a long way off.

For more information and background on SNICKER, see the draft BIP, follow the bitcoin-dev mailing list discussion or read Gibson’s (slightly outdated) blog post on the proposal.

The post SNICKER: How Alice and Bob Can Mix Bitcoin With No Interaction appeared first on Bitcoin Magazine.