Shamba Network Sows the Future of Sustainable Agriculture in Africa

Financial inclusion and access to global finance has always been lacking in sub-Saharan Africa. Although gains have been made, as of 2021 only 55% of the population had a bank account, according to the World Bank. The problem is more acute in rural areas, where banks are few and far between. Mobile banking solutions that allow users to transfer money and access microfinance, including lending and insurance, through their cell phones have existed since 2007, but their effectiveness in supporting economic development is contested.

More than that, these services are not geared towards addressing climate change, which disproportionately affects sub-Saharan Africa. While financial tools to address and mitigate the effects of climate change exist, they remain out of reach to some of the poorest populations in the world, which are the hardest hit.

Climate risk insurance, which offers compensation in case of, for example, crop failure due to drought, is often too expensive. The carbon credit market, an increasingly popular solution for combating climate change, in which certificates of carbon-alleviating projects are exchanged, depends on middlemen, such that often local communities see little to no benefit from the trades. Even if the middlemen problem was solved, carbon credits often involve hundreds of thousands of hectares of land, which is far from what the vast majority of sub-Saharan farmers have available.

In short, lack of protection from climate change is creating financial risk to a population already lacking in financial services. The problem before us is how do we combat climate change and mitigate the financial impact of climate change on sub-Saharan Africa?

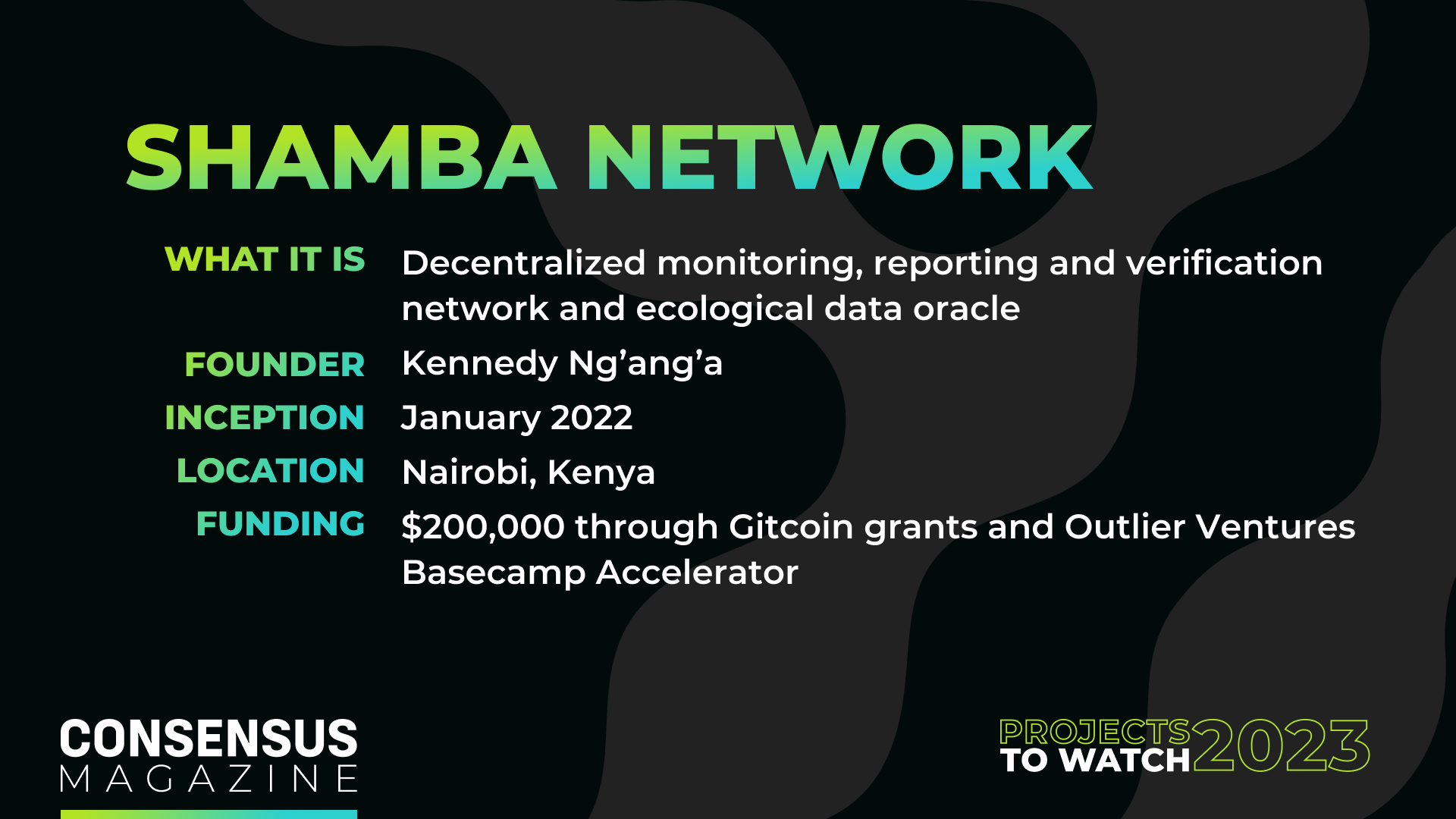

SHAMBA NETWORK

Millions of people in sub-Saharan Africa are smallholder farmers, many of whom practice subsistence farming. They are growing enough food for themselves and their families but not enough to trade on the market for money or to barter for needed goods.

“Agriculture is the backbone of how most households [in rural Kenya] are able to support themselves,” said Kennedy Ng’ang’a, founder and CEO of Shamba Network. He studied geospatial engineering in Nairobi and later worked at the International Centre for Tropical Agriculture. He also has several family members who are smallholder farmers and has a wide-angle perspective on how essential working the land is for his homeland.

“I’ve seen for myself how important agriculture is both for people as well as for our economy at a national level, and I think there’s still a lot of things that can be done to improve it.”

Ng’ang’a believes by giving farmers the right knowledge and tools to practice sustainable agriculture, “there is a lot of potential for them to be able to take control of their own destiny.” That means learning how to farm in a way that doesn’t deplete their land and ensures its productivity for decades without the need for industrially produced fertilizers.

“Most of the agricultural land in Africa is being degraded, especially because of the synthetic fertilizers,” he said. That is “being driven mainly by big multinationals that are controlling input supply,” including seeds.

Ng’ang’a started Shamba Network last year to assist farmers with sophisticated data and insights to improve their farming outcomes.

Shamba’s first priority is to promote sustainable agriculture that will not deplete farmers’ land – and therefore, their livelihoods. Second, Shamba is using blockchain to give farmers access to emerging financial paradigms like climate insurance and carbon markets.

Shamba is a multifaceted project, tackling both socioeconomic issues such as financial inclusion and development equity, as well as environmental problems, from encouraging local communities towards more sustainable practices, to ultimately tackling greenhouse gas emissions through carbon credits.

Based out of Nairobi, Kenya, Shamba Network uses blockchain, remote sensing technology and statistical sampling to solve specific problems the region and its people face. The explicit goal is to lower the costs of climate insurance by improving the tools for monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV). That’s a term often used in carbon marketplaces, meaning software and hardware used to measure and verify data points such as carbon dioxide emission. Along the way, Shamba is promoting regenerative practices that will, by implication, also combat climate change. Eventually Shamba aims to allow groups of smallholder farmers to make money by issuing carbon credits.

Ng’ang’a became acquainted with Web3 a few years ago, and with his agricultural expertise became particularly interested in regenerative finance (ReFi), a brand of crypto that aims to build systems that support and promote sustainability. As he investigated further he noticed that lack of data created roadblocks for innovation. “People had a lot of ideas around what they wanted to do, but they didn’t necessarily have the data to back it up,” he said.

Shamba’s goal is to build ecological data oracles and smart contracts. Ecological data is information that describes the natural attributes of an ecosystem. Oracle technology is what brings this MRV information on the blockchain, the connective tissue between on- and off-chain data.

The Shamba Network tracks ecological data from over 30 free satellite databases from various universities and organizations around the world that capture air quality, precipitation, temperature, vegetation, etc., along with on-the-ground data taken from statistical sampling.

If, for example, there is a drought on a farmer’s land, satellite data will show a lack of precipitation. The oracle will feed this information to the blockchain, triggering a smart contract so that climate insurance can be automatically paid out to them. This can lower the cost of climate insurance by as much as 40%, Ng’ang’a said.

Shamba has worked with microfinance company Fortune Credit and Diva Protocol to insure 150 cattle herders in northern Kenya. For example, if the vegetation level in the region falls below the certain threshold at which the livestock might face starvation, a payment will be made to the herders. The financial partner in the project works with thousands of herders and farmers, which gives ample space for Shamba to scale its impact.

These processes used to be done manually. An insurance provider would be out in the field to check the initial and final condition of the land, which added a lot of costs to the insurance. Shamba fully automates the process, such that “nobody needs to go process a payment” and the entire process is conducted through smart contracts.

“So once a farmer signs up for a product, they ensure that for one, it is going to be executed in a timely fashion. But also most importantly, nobody can step in and block their payment,” said Ng’ang’a.

Shamba’s data collection and analysis features could improve carbon credit measurements as well. The decentralized MRV tools could help ascertain the ecological impact of a group of farmers implementing sustainable or regenerative practices. This verification is crucial for creating high quality carbon offsets. A group of smallholder farmers could claim carbon impact from implementing sustainable farming practices, and the decentralized MRV tools could be used to verify this impact and create carbon credits.

Shamba’s success, to a large extent, relies on a wider ecosystem of Web 3 climate solutions. The project is part of a host of such projects: Web 3 climate data aggregator dClimate, nature credits marketplace Regen Network and forestation protection Open Forest Protocol. Together they are building the ecosystem in which projects like Ng’ang’a’s can flourish.

How Shamba helps farmers on the ground

In Gatanga, an area down roads twisting through steep, vegetation-covered hills a couple hours north of Nairobi, Shamba is laying the groundwork for smallholder farming communities to eventually issue their own carbon credits, along with local NGO Youth Action for Rural Development (YARD). The credits will represent organically grown fruit trees that will then be sold to international markets.

The trees clean the air, prevent soil erosion and produce healthy food. “Obviously, we know how trees work, they clean the air. So by planting the trees, we will be breathing fresher air,” and will be healthier, said Terry, who like the other farmers, only gave her first name. YARD has been teaching local farmers about sustainable farming techniques and healthy habits since 2002.

These farmers’ groups self-organize to pool and manage their resources. Some of them essentially run their own bank; they pool money and loan it to members when it is needed. Because the farmers are already managing money collectively, they have a process already in place for distributing any funds carbon credits, the YARD’s founder, Sebastian Wambugu Maina, said.

The funds could be crucial. To buy the equipment needed to grow 3,000 avocado trees, Terry’s group spent about KSH 5,000 ($37.30), but now they have no money to continue the project. “We need financial resources,” she said. “Obviously the income is not going to come tomorrow, or in two months’ time,” but they are trying to build a sustainable business that will continue indefinitely.

Shamba’s funding challenge

Shamba generates revenue through commissions from the insurance fees and eventually will also benefit from carbon credits sold.

But in order to grow the project, Ng’ang’a says the startup also needs funding. Much like with other projects in the regenerative finance space, funding can be difficult. The market for these products is either small or in some cases non-existent, so typical investors might find it a hard sell. There are however, ESG-oriented investors including Mercy Corps Ventures or Cerulean Ventures that have shown interest in such startups.

Ng’ang’a has so far sustained the project through Gitcoin grants, as well as some funding from a Filecoin accelerator. For about a year, seven people around the world have been building this full time with only $200,000 in funding. The founder has been trying to boost growth with traditional equity funding, but it has been an uphill battle.

“Most of the venture capital funding doesn’t necessarily come from Africa. It’s people who can stomach a lot of risk, who actually bet on African entrepreneurs,” Ng’ang’a said. “So we are always trying to find other ways to survive, even as we try this [equity-based funding].”

Edited by Jeanhee Kim.