Sam Bankman-Fried Demonstrates Ineffective Altruism at Its Worst

One year ago, CoinDesk’s Ian Allison sent me the FTX balance sheet and asked for my take. I laid out what I saw, asking several times whether it was real, because a balance sheet that bad just did not seem possible given all we’d read about Sam Bankman-Fried, Alameda and FTX over the preceding years. It was very real, and Ian brought down the house with his award-winning reporting. I’m proud to publish my latest thoughts on SBF here on CoinDesk.

They say the road to hell is paved with good intentions. Maybe so. It may also be that those who choose the road to hell try to paint over it by claiming to have good intentions. Perhaps they even use their supposedly good intentions to justify actions that are anything but good.

Take the case of Sam Bankman-Fried. More commonly known by his initials, SBF, he briefly held the title of world’s richest 30-year-old, with an estimated net worth of $20 billion. His fame rose as he pledged to pursue “effective altruism” by donating most of this wealth to popular causes. These good intentions were a major part of the publicity campaign that differentiated his company from its competitors.

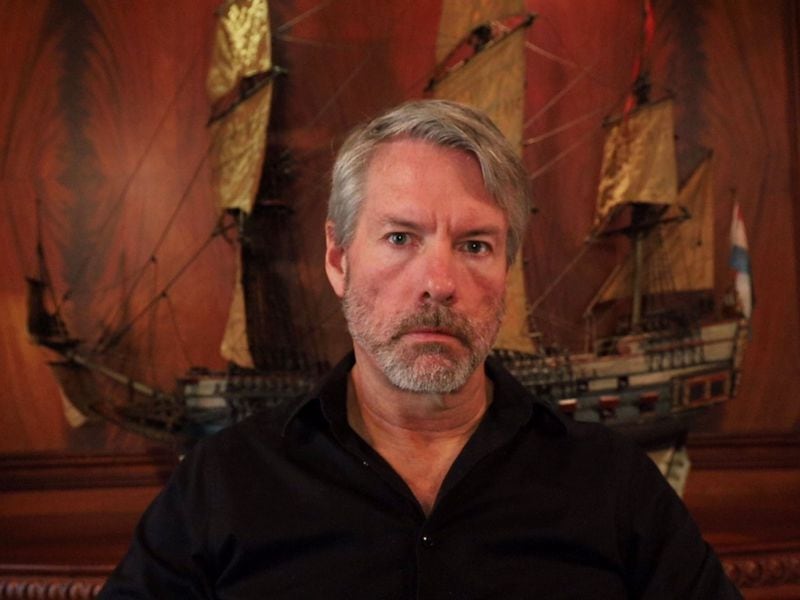

Cory Klippsten is the CEO of Bitcoin financial services firm Swan.com.

However, the road SBF took to obtain his riches and pursue his proclaimed good intentions was one filled with extreme carelessness and negligence, and likely also fraud. Today, his fortune is wiped out, and he faces criminal charges that could result in over a 100-years of jail time. All of the well-intentioned benefits he pledged have instead been replaced by terrible damage to the lives of his customers.

This would be a short cautionary story but for one curious fact. Despite the wreckage he caused, and the accompanying failure to do good, there remain numerous voices sympathetic to SBF.

Chief among them is well-known author Michael Lewis. Throughout his new book on SBF and FTX, “Going Infinite,” he paints a portrait of SBF as a misunderstood genius whose intentions were pure. On his book tour, Lewis has continued his sympathetic depictions, saying things like this on MSNBC: “I think of him as a creature of modern finance. At almost any period in history, he’s like a high school physics teacher.”

If Lewis is correct, he should be indicting modern finance wholesale. After all, SBF, by skipping the effort of honestly earning the money he gave away (or which he spent on lavish properties, celebrity endorsements, stadium naming rights and sponsorships of extravagant galas), never actually performed a genuinely altruistic deed.

Instead, his intentions led to him committing dirty deeds. Is this what personifies modern finance?

In spending money that was never his in the first place on “good causes,” SBF defaulted on the most important prerequisite for being generous – having something of yours to be generous with.

How can his actions elicit sympathy instead of outrage? It appears to come down to a growing view that honest work required to provide a service is not as important as altruistic pledges.

Had SBF made it a priority to run a legitimate and responsibly managed business that earned honest profits, he would not have become the 41st richest American (according to Forbes). He also would not have garnered the unearned admiration he bought with stolen money.

The SBF story is an extreme example of the ever-growing phenomenon of putting lofty desires ahead of more important requirements – delivering excellent products.

If the pressure to appear altruistic was not so important, SBF might actually have focused his efforts on laying the foundation of building a sound business.

It ultimately should come as little surprise to us that if we do not show appreciation for the hard, time-consuming work required to deliver great services, the quality of what companies deliver us will decline.

Nor should we be shocked when cases like that of SBF arise in which the service itself turns out to be a complete fiction – doing none of what it promises customers, but instead directing all its efforts to those unrelated, altruistic practices which receive praise.

The story of SBF serves as a warning that it is crucial that companies prioritize building and operating good businesses – and that the standard that we use for judging them as good is how well they serve their stakeholders. There can, of course, be room for companies to be charitable.

However, if charity comes at the cost of running a company poorly, or worse, fraudulently, that charity will not last, and all the other valuable offerings the company exists to provide will also erode or disappear.

Edited by Daniel Kuhn.