Jesse Powell: Bitcoin Banker

Jesse Powell is used to playing the tougher hand.

When he played the card collectibles game Magic: The Gathering with fellow bitcoin OG Roger Ver, Powell picked the decks that required more silence and concentration. Ver picked the simpler hands and chatted with his opponents, Ver told CoinDesk in a recent interview.

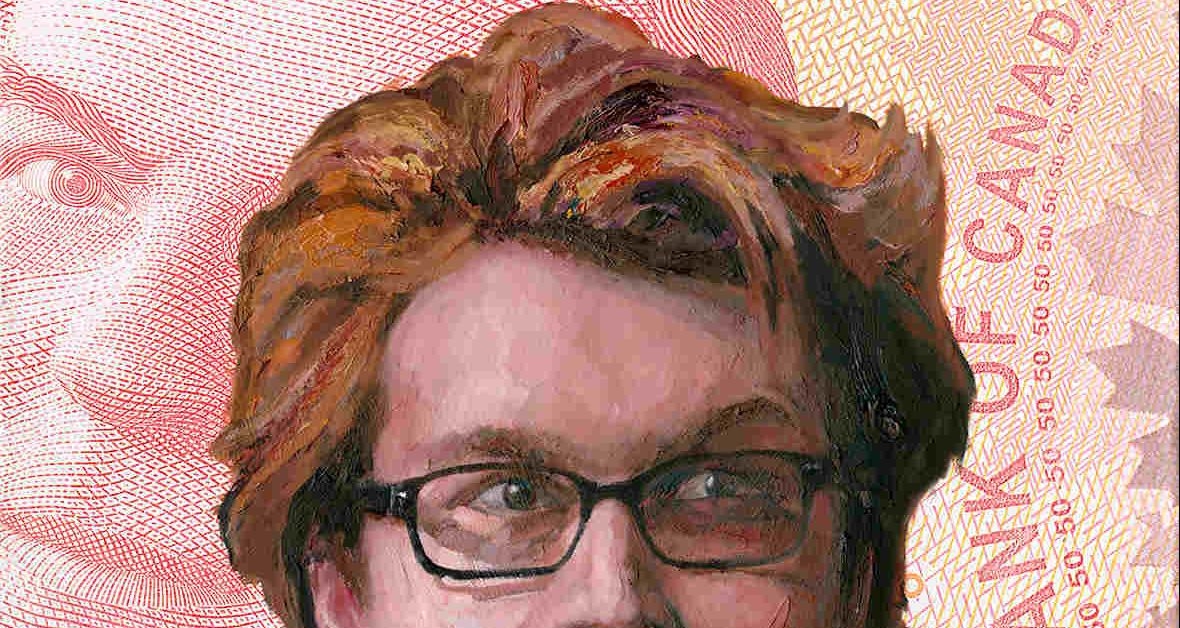

This article is part of CoinDesk’s Most Influential 2020 – a list of impactful people in crypto chosen by readers and staff. The NFT for the artwork here – by Matt Kane – is available for auction on Super Rare, with 50% of the proceeds going to charity.

Choosing the more difficult option is part of why Powell went to Wyoming to help develop crypto-friendly laws around the state’s special purpose depository institution (SPDI) community bank charter and why Kraken was the first exchange to apply for the charter, Ver said. The charter requires around $25 million in equity capital, new staff and directors, and compliance teams to regularly perform proof of reserves audits.

Powell and Ver got together for MTG when they were teenagers, and both entrepreneurs fell down the bitcoin rabbit hole together in 2011. (The origins of the name of the now-bankrupt Tokyo-based exchange Mt. Gox was Magic the Gathering Online Exchange.)

Powell and Ver helped Mt. Gox creditors track down some of the 850,000 bitcoin that went missing with the bust. The experience gave Powell the ability to teach Wyoming about fake exchange volumes and the many ways exchanges can harm customers, said Chris Land, general counsel at the Wyoming Division of Banking.

“The New York Stock Exchange doesn’t have fake volumes,” Land said. “It’s heavily regulated and trusted. I think [coming to Wyoming] shows something about Jesse’s commitment to running a real exchange.”

Pursuing a SPDI bank charter is part of Powell’s choosing the tougher deck, Ver said. But integrating crypto with the traditional financial markets is going to further bitcoin’s adoption.

“If you remember the original ‘Alien’ movie, the alien goes inside of the person, and it’s like inside the person’s chest, and it’s growing and growing and growing, and then all of a sudden it pops out of the chest,” Ver said. “I see cryptocurrencies like that for the traditional banking system and legacy financial systems. They’re growing inside and they’re going to integrate directly with them, but at some point they’re just going to pop out and everything’s going to be crypto.”

Out of the 150 companies that expressed interest in setting up in Wyoming, Kraken and Wyoming blockchain pioneer Caitlin Long’s Avanti Financial are the first to get their foot in the door. (Avanti had to raise $5 million in equity capital whereas Kraken was in a position to use its balance sheet to build the bank).

“There are others in the wings, but it was a very heavy lift just to get the bank charter application in there’s so many details related to how you start a bank,” Long said.

Being the first company to receive the charter, Kraken is stepping into a space while the rules are still being written. The Wyoming Division of Banking is currently working with prominent Washington, D.C.-based consulting firm Promontory Financial, leveraging current Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council manuals such as the Comptroller’s Custody Handbook to create guidance for SPDIs on handling digital assets.

Trying to merge traditional markets with digital asset markets hasn’t always been as productive as the conversations Powell had in Wyoming. In 2013, Powell spent a lot of time talking to European regulators about crypto when those regulators had no solid guidance to offer at the time, said former Kraken COO Michael Gronager, now Chainalysis CEO. Powell persevered in Europe, just as he’s now taking the harder path in Wyoming.

Still, Powell remains generally skeptical of banking regulators who’ve created an atmosphere where banks can deny legal crypto firms and their customers basic banking services, while being allowed to make risky investments. “The problem with most banks is that they’re allowed to gamble while most people just need basic access to payment rails,” Powell said.

With the emergence of the SPDI, the crypto industry will now get more than a handful of U.S. banks to choose from. This comes around the same time as the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency announced in a letter in July that federally regulated banks could provide custody services for crypto. The OCC’s acting comptroller, Brian Brooks, also released a proposed rule in November that would push banks to serve all legal businesses, and said on CNBC’s Squawk Box on Friday he hopes to provide clarity around banks plugging “directly into blockchains as payment networks.”

Kraken’s bold SPDI move in Wyoming positions the exchange to do custody crypto for institutions without a trust company, bank retail customers without another bank and connect directly to the Federal Reserve’s payments system. This year, crypto companies – often the pariahs of finance – started to find it easier to build banking relationships, and we saw the beginnings of a convergence between the previously separate worlds of crypto, fintech and more traditional finance.

Jesse Powell is leading crypto’s push into the future where companies like Kraken are integrated into the mainstream system.

Powell first discovered crypto when he was CEO of a company that sold virtual items and currencies for online games like World of Warcraft and Diablo II. At virtual world services company Lewt, Powell offered what was like a bank for the digital assets of gamers. Since game developers were essentially self-regulatory bodies for gamers, the developers also had control over gamer assets.

“There was nothing we could do about a game company shutting down accounts other than try to spread the assets out across many disconnected accounts so that the damage would be mitigated in a mass ban scenario,” Powell said.

To this day, only a handful of banks in the U.S. openly court the crypto sector

Kraken’s early team relied on Powell’s standing in the online gaming space to later gain employees for what would be San Francisco-based Kraken, Gronager said.

While “buy bitcoin, short the banks” is a common mantra in the cryptocurrency industry, crypto executives like Powell recognize the need for fiat on-ramps, with the goal to allow users to deposit fiat directly into their accounts at exchanges.

In 2013, the fledgling exchange ran into banking partner rejections from 30 banks before it connected to Berlin-based Fidor, Gronager added.

“It was one of the defining moments where we were, like, how do we actually get this off the ground and how do we launch?” Gronager said. “Because it was great tech, but we needed a bank account.”

To this day, only a handful of banks in the U.S. openly court the crypto sector, among them Silvergate in California and Signature and Metropolitan Commercial in New York. Earlier this year JPMorgan Chase, the country’s largest bank, opened accounts for the Coinbase and Gemini exchanges, both of which had submitted to the stringent oversight of the New York State Department of Financial Services (NYDFS).

Kraken was originally domiciled in New York, but left in 2015 after citing the costs of the NYDFS’ BitLicense. Kraken also submitted a comment on New York BitLicense when it was proposed, but Powell said that “crony capitalism” got in the way of its development. “Obviously [BitLicense architect Ben] Lawsky had an agenda,” Powell opined. “He left and started up a consulting firm to help people get the BitLicense.”

In the bull run of 2017-2018, the exchange had only a handful of banks to run transactions for thousands of new customers. Powell watched as newcomers lost out on bitcoin capital gains while slow bank transactions inhibited other investors.

Since then, Kraken has made connections to around 30 banks globally. Now, after jumping through a few more regulatory hoops, it’s on track to receive a certificate of authority from the Wyoming Division of Banking to operate its own bank.

“That’s like the holy grail,” Powell said. “Instead of having your paycheck go to Bank of America and you have to send it back out to the exchange, you could just have your paycheck deposited directly into your Kraken account.”

Wyoming, with its libertarian leanings and nimble legislature, was an attractive option for Kraken, Powell said. Powell himself went to many Libertarian Party meetings and the Libertarian national party convention in his late teens and early twenties, Ver said.

In Wyoming, Powell testified at two Wyoming Blockchain Task Force meetings and also came to meet Gov. Mark Gordon in Cheyenne before Kraken applied for the charter itself. (Powell showed up to the meeting with the governor in “jeans and a sweater,” Long said, but when he appeared on Zoom for Kraken’s hearing before the banking committee, he was dressed in a suit and tie.)

As the only crypto exchange executive present at these meetings, Powell said he wanted to create precedent in U.S. law where it hadn’t existed before.

“If something comes up in court, they might be trying to figure it out for the first time, so it might just come down to the judge,” Powell said. “Whereas this stuff is explicitly spelled out in Wyoming … I think a lot of other states are going to copy it.”

Powell came to the task force through bitcoin podcast host Trace Mayer. In meetings at Wyoming, Powell employed the same tactic as he had for Magic games.

“He’s very deliberative,” Long said in reference to Powell’s input on hot topics in the industry. “He doesn’t speak out of turn.”

Powell helped create favorable conditions for consumers financially challenged by forks or air drops, Long said, while also balancing the liability that exchanges hold. In a fork, a splinter currency is created and anyone who held the original coin at the time of secession can claim a like amount of the new one; airdrops are giveaways of new tokens to users with existing wallets, the blockchain industry’s equivalent of junk mail.

“If the intermediary claims the fork proceeds, under Wyoming law they have to distribute the fork proceeds to their customers,” Long said. “[They made] sure they were not required to go claim the fork properties, because then anyone could force the exchange to do the engineering work, including on insecure protocols.”

The charter requires SPDI banks to cryptographically verify to an auditor that the bank’s reserves are there. A longtime advocate of proof of reserves, Powell hopes Wyoming’s rules will raise standards in the industry. In the last few years, Powell said, calls for proof of reserves have waned due to a relative lack of major hacks and a shortage of auditors who are able to perform the necessary forensics work.

“The auditor really has to be willing to take some reputational risks themselves because there is a chance that they are somehow duped in the process of running the audit,” he said. “We’ve seen all these DeFi yield farming protocols get hacked, and they’ve all been audited. There’s some auditor who’s signed off on all of these things.”

While Powell is interested in decentralized exchanges and yield farming strategies, he said he wishes that the DeFi (decentralized finance) sector would spend more money on security and compliance. (When DeFi protocols “blow up,” they usually come to centralized exchanges or wallets asking them to freeze funds that are being drained from the contract or to track down who hacked the protocol, he said; Kraken is also looking to be a gateway for crypto investors into DeFi protocols.)

“If you’re expecting to have like tens or hundreds of millions of dollars secured by this piece of code, maybe it’s worth like $5 million to make sure that it’s all secure at least, rather than getting one $50,000 audit.”

Powell also still sees several security issues with the world of centralized cryptocurrency firms that he’s used to operating in. Firms that have holes in their balance sheets can cover them with short-term loans for audits, he said, and crypto exchanges like the now-defunct QuadrigaCX can appear to be professional outfits while being operated by only a handful of people.

Powell also hinted at breaking into the saturated crypto lending space, which has suffered from hundreds of millions in margin calls in March, undisclosed business practices, and a bankruptcy in 2020.

How does this orange grove case relate to cryptocurrency?

“Obviously it wouldn’t be like a normal fractional reserve bank where they’ve got infinite amounts of money to lend,” Powell said. “It would be either lending from our own balance sheet or we could borrow coins from other people and then lend those coins out.”

Powell is also thinking about what a bank branch in a tech area like San Francisco or Berlin might look like, though he’s still wary of encouraging bitcoin holders to be seen in public.

Next, Kraken is focusing its lobbying efforts on the Securities and Exchange Commission and Commodity Futures Trading Commission as well as trying to get the U.S. Congress to provide updated legislation for cryptocurrencies outside of the Howey test for securities, which dates back to a 1946 U.S. Supreme Court ruling about orange groves.

“We think there need to be some explicit carve-outs, some clarity,” he said. “Regulators are trying to interpret it, like ‘what does it mean?’ How does this orange grove case relate to cryptocurrency?”

Powell believes the money printing from the U.S. Federal Reserve during the pandemic-induced recession will drive more awareness of crypto. But he still worries the industry has not “hit escape velocity yet, globally, as a movement.”

“I think there’s still things governments can do to shut it down if they really get scared,” he said. “I’m a bit pessimistic about this. But I think that politicians in the long run are just self-serving. To the extent that we can put crypto in the pocket of every politician, they’ll likely work to benefit themselves.”

Powell added that he’d feel more comfortable once U.S. politicians begin accepting and keeping campaign donations that are denominated in crypto.

“I think there will always be a compulsion to go back to a human-managed currency because of the great power it has,” he said. “We’re still fighting against governments and [Internet Service Providers] for our rights on the internet.”