How to Build a Compliant Crypto Exchange Post-Coinbase

I developed something of a reputation for being a skeptic about the legal propriety of selling cryptocurrency tokens in the United States. I used to write about this extensively, particularly in 2017 when I was studying for my master’s in law and, accordingly, had more free time and latitude to say what I wanted.

Moreover, I held this position when it was unpopular and non-obvious, unlike the recent crop of crypto critics like former government lawyer John Reed Stark (who seems to take endless glee in kicking the industry while it’s down). See, for example, on July 9th, 2014, when my friend Tim Swanson and I were quoted in a CoinTelegraph article, “Mitigating the Legal Risks of Issuing Securities on a Cryptoledger,” when I said that “[Virtually] nobody has done this correctly. To date I have not seen a single crypto-security that has been properly structured.”

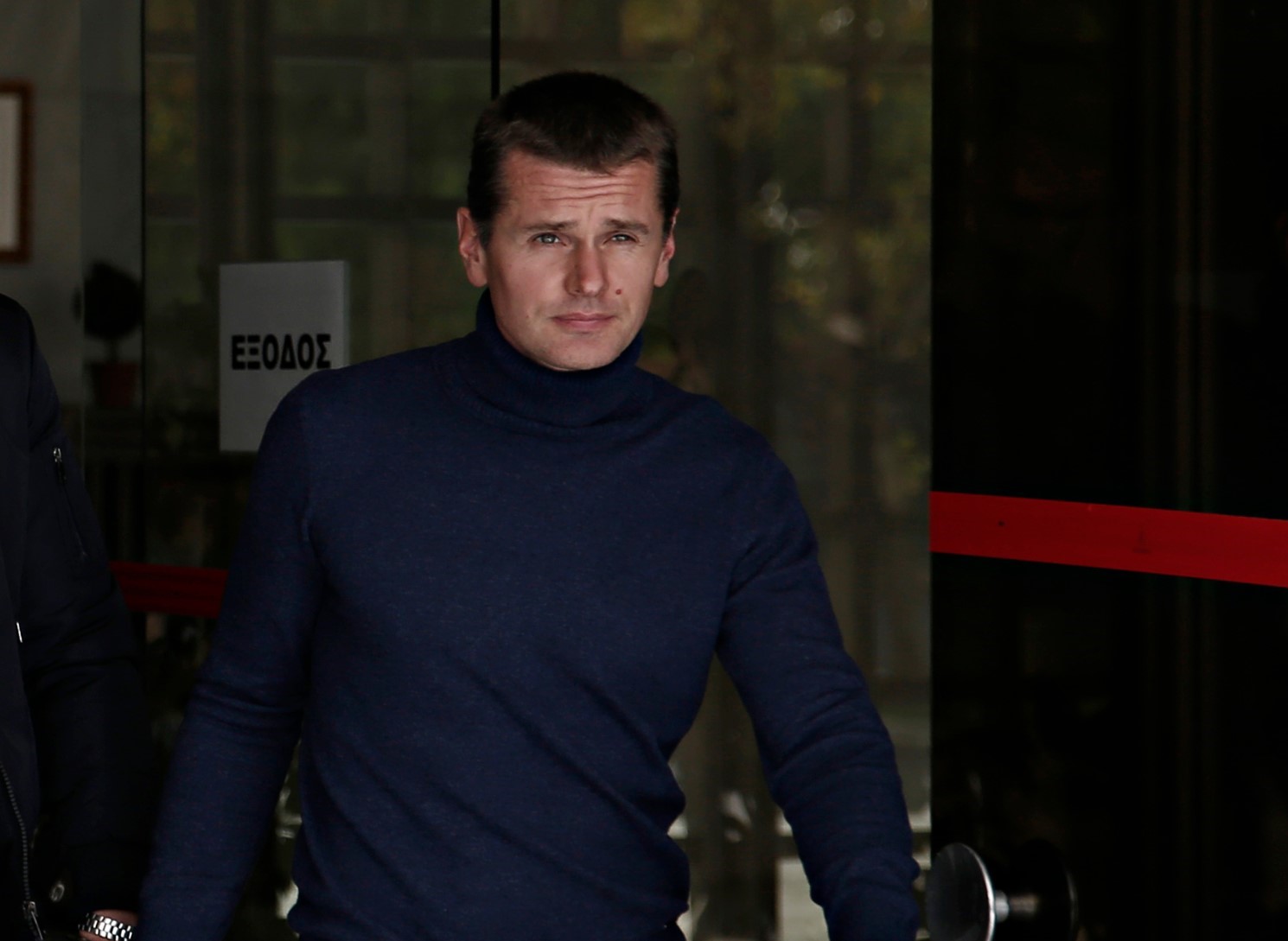

Preston Byrne is a lawyer and partner of Brown Rudnick’s Digital Commerce Group.

People thought I was crazy at the time. Others probably thought I was just a jerk. The truth is probably somewhere between the two. Keep in mind, of course, that in 2014 the idea of an “initial coin offering” (ICO) didn’t really exist; entrepreneurs like Joel Dietz marketed his “Swarm” crowdfunding token as “crypto-equity,” a term which fell into disfavor by more sophisticated projects like Ethereum which, only a month after I was quoted in the CoinTelegraph article, launched its ICO. But even that wasn’t called an ICO. That, presumably per whatever advice was given to Joe Lubin by his lawyers, was a “sale of crypto fuel for the Ethereum network.” Or as the New York Attorney General alleged in its recent lawsuit against KuCoin, a security.

Ethereum subsequently exploded in 2017 and with it came a thousand imitators and other variations just like it. U.S. regulators were slow to respond. Then-SEC Director Bill Hinman added fuel to the ICO fire when made his famous “Hinman Speech” which set out the (now-discredited) “sufficiently decentralized” exception to the Howey test. Keeping in mind that Hinman was based out of San Francisco, the general assumption among those of us who were not in the cool SF venture-capitalist crowd was that they had successfully convinced that office that Ethereum – a popular investment out there – was the next Internet and the best thing for the government to do would be to get out of the way and let Ethereum prove it.

I think it is safe to say, five years later, that Ethereum has not cracked a lot of the scaling issues it would have needed to do to become the next Internet. With those broken promises on one side, perhaps it is not surprising that the government has decided to restore the status quo ante, with the NYAG’s lawsuit against KuCoin.

Confusion and weird settlements

What followed the Hinman speech can only be described as confusing. Until the Hinman speech, the SEC really had only gotten involved in the crypto business in cases of obvious and notorious fraud. The first such case that I can recall was the case of SEC vs. Trendon Shavers and Bitcoin Savings and Trust (a Ponzi scheme) and SEC v. GAW Miners, Joshua Homero Garza et al. (another Ponzi scheme involving the sale of “mining contracts” and a $20 stablecoin called “paycoin”).

In terms of non-fraud enforcement, the SEC started to bring its first set of enforcement actions, announced by way of settlements, with a number of coin-related projects in late 2018, only months after the Hinman Speech was published. The first such settlement, with a founder of early decentralized exchange, or “DEX,” EtherDelta, was announced on Nov. 8th, 2018; the SEC claimed that the DEX operator was operating an unregistered exchange, which necessarily implied that the SEC took the view that some of the assets on EtherDelta – being Ether and ERC-20s – were securities. Ten days later, the SEC announced its first settlements with two otherwise completely unmemorable ICO issues, Airfox and Paragon; both respondents agreed to register their tokens as securities (which does not appear to have happened as far as I can tell).

What followed over the next year was a range of weird settlements which failed to serve as a deterrent to further ICO issuance being conducted at the same time as a bunch of weird transactions which tried to pretzel their way into compliance with the non-guidance guidance issued by Bill Hinman. EOS, for example, which advertised its product on a giant Times Square billboard during Consensus 2017 and raised north of $4 billion in crypto (as valued at the time), was somehow allowed to skate by paying a $24 million fine – and not even a requirement to register!

Other projects were not so lucky. Kik Interactive, Telegram, and Ripple Labs reached launched absolutely gargantuan ICOs; both Kik and Telegram lost badly in federal court, and I do not rate Ripple’s chances. Similarly the much-smaller LBRY project, based in New Hampshire and which pre-dated EOS by some years, was not, as far as I am aware, offered a settlement deal with the SEC which would have permitted their business to continue operating; the only logical reason I have been able to deduce for this is that the SEC’s Boston office wanted a scalp and the only place you’ll find a crypto startup in New England is in New Hampshire.

This brings us to the Coinbase complaint. Nothing about it will come as a surprise to any attorney who has been practicing in the U.S. after 2018.

The charges alleged are numerous. The SEC accuses Coinbase of violating the registration requirement of the Securities Act of 1933 in relation to its custodial staking offering.

It also charges Coinbase with violating the Exchange Act’s registration requirements, which require anyone effecting transactions in securities to register and be supervised by the Commission. Furthermore, Coinbase is charged as operating as an unregistered broker-dealer and with operating as an unregistered clearing agency, being “any person who acts as an intermediary in making payments or deliveries or both in connection with transactions in securities or… provides facilities for comparison of data respecting the terms of settlement of securities transactions.”

I am not going to bore you by quoting chapter and verse on broker-dealer registration requirements. I also won’t go into a detailed Howey analysis on many of the coins mentioned in the complaint – including Solana, ADA, Matic, Filecoin, SAND, AXS, CHZ, FLOW, ICP, NEAR, VGX, DASH, and NEXO. The important thing here is that the SEC is seeking, as a remedy, a permanent injunction against Coinbase from operating an unlicensed exchange. If they can get one of the tokens to stick and win at trial, they may be able to shut down Coinbase’s core business completely.

What did surprise me is that it took this long. Back in 2017, I hypothesized that one day there would come an event – one I referred to as the law enforcement would launch something akin to “simultaneous dawn raids at the major exchanges and the homes and offices of the major ICO promoters, with a variety of agencies in a variety of countries co-ordinating their activities.” It’s hard to tell whether we’re at the beginning of a process that extensive, but if the SEC is going after Coinbase, no one in Coinbase’s business is safe. I called that event “The Zombie Marmot Apocalypse,” said it was massively bearish for crypto and I think it is safe to say that it is now upon us.

The question then turns to what comes next. Crypto isn’t going anywhere, so I think the answer is “new exchanges that aren’t carrying all this regulatory baggage.” In terms of how that might look, here’s my current thinking:

-

Paradoxically, there is probably no better time – other than 2012 – to start a crypto exchange than today. For the first time since perhaps the start of Bitcoin itself, compliance will cost less than non-compliance. Existing industry giants have a lot of legal-technical debt they need to work through which will distract them and cost enormous amounts of money.

-

Crypto is not going to die. In places where it is growing most quickly, particularly Latin America and Africa, there is neither the political will nor the harmonized enforcement capacity to shut it down.

-

Making companies like Coinbase treat crypto tokens as old-fashioned securities is like trying to regulate Starlink like we regulate road traffic. Equally, expecting the U.S. government to simply just let crypto happen was not realistic. Increased lobbying efforts and an openness to compromise by U.S. crypto giants will result in a middle path in the U.S. which will regularize crypto business within the next five years if not sooner.

-

The companies that will succeed will have a growth strategy which doesn’t include the United States, and will then need to be ready to move to the United States on hair-trigger alert once regulations are favorable – or, in the alternative, they’ll need to develop a subsidiary that operates like INX and gets the appropriate regulatory approvals. I suspect that regulations will eventually loosen up so that companies like INX can operate more like companies like Coinbase and Gemini do today. To achieve scale, startups will need to build a toehold in countries with substantial populations of English-speaking crypto users which don’t ban ICOs and permit exchanges to trade spot crypto without regulating them as broker-dealers or clearing agencies.

-

The only G20 country can think of which satisfies these criteria is the United Kingdom. The UK should be used as a launchpoint to access English-speaking Africa and India while the U.S. gets its act together and (likely) has a change in Presidential administrations to one that doesn’t want to completely eliminate avenues of escape from the dollar.

So. Crypto’s not dead, it’s just in need of a little legal tune-up. May the best and most compliant startup win.