Dutch Central Bank Forced To Backpedal On Bitcoin Address Verification Procedures After Court Ruling

The Dutch Central Bank has lost a legal battle over its uninformed and bureaucratic bitcoin address verification requirements.

Bitonic, the oldest Bitcoin exchange in the Netherlands, recently had its day in court with the Dutch Central Bank (DCB). At issue was the legitimacy of DCB’s mandate that Bitonic (and other Bitcoin exchanges and custodians operating in the Netherlands) implement very stringent “address verification procedures” in order to obtain the legally required registration with the DCB.

The judge’s opinion in the case was generally favorable towards Bitonic’s complaints, and, on April 7, she gave the DCB six weeks to review its policy. Wednesday evening, the DNB formally acknowledged the legitimacy of Bitonic’s complaints and revoked its mandate for stringent address verification requirements as part of the registration regime.

The victory is crucial to the continued vibrancy and profitability of the Dutch Bitcoin industry.

Background To The Court Case

The run-up to the court case already started back in May of 2018, when the European Union passed the fifth Anti-Money Laundering Directive (AMLD5).[1] This directive required the member states of the European Union to implement into their laws certain regulations for cryptocurrency exchanges and custodians.

Broadly speaking, AMLD5 demands that cryptocurrency exchanges and custodians (1) perform background checks on their customers, (2) monitor and report unusual transactions, (3) and register with a relevant regulatory authority.

Implementation of the AMLD5 directive into Dutch law was somewhat chaotic and contentious to say the least. The main discussion point centered on the AMLD5’s mandate for a registration regime (requirement 3 above).

Initially, the government’s concept implementation of AMLD5 into the law at the end of 2018 called for a licensing regime, rather than a registration regime. The former is a much more burdensome requirement than the latter.

This resulted in substantial push-back from the Dutch Bitcoin industry and various other actors, including the Netherlands’ Raad van State,[2] a key institution for legal review in the Netherlands. Superseding the requirements of AMLD5 by implementing a licensing regime proved unjustifiable, and the government was forced back to the drawing table.

That should have been the end of the discussion. But it wasn’t.

While the government had indeed changed some of the wording in the proposed law and in particular now spoke of a “registration regime”, many believed that the law still de facto imposed a licensing regime.[3]

So, again pressure was exerted on the government. After more than a year of discussion about what should have been a straightforward implementation of a registration regime on the basis of AMLD5, the Dutch Bitcoin sector could finally have a sigh of relief in April 2020 when the government stated unambiguously that the industry should fall under a registration regime, not a licensing regime, and explained what such a regime entailed.

In the words of Wopke Hoekstra, Minister of Finance at the time of these discussions, “Registration is something you do, a license is granted to you. [A license] is really something different. The bar is at a different level.”[4]

This seemed to leave little room for ambiguity to the DCB who was appointed as the “relevant regulatory authority” to oversee the registration regime.

This is why the Dutch Bitcoin industry was left rather puzzled on September 21 last year. On that day, already several months into the processing of registration applications and the deadline nearing, the Dutch Central Bank casually conveyed via a webinar that any withdrawal of bitcoins by a customer from an exchange or custodian to their own wallet would require stringent address verification procedures.

Failure to implement said procedures before November 21 (the deadline for the registration), so Bitcoin exchanges and custodians were told, would result in a refusal to grant registration. Any such refusal for a company would, in turn, would essentially require them to cease operations at that point.

What exactly was the DCB mandating with these address verification measures?

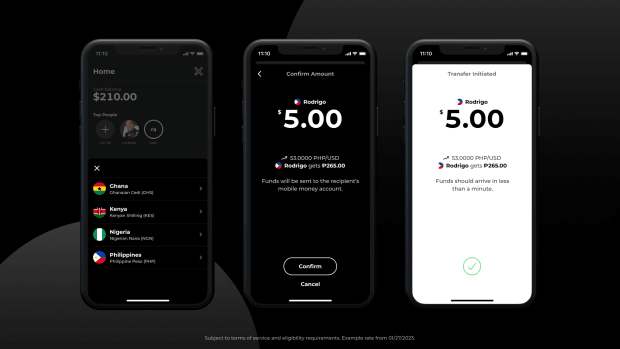

Essentially, the DCB mandated that whenever a customer withdraws bitcoins from a custodian or an exchange, the service provider would need to take radical measures to verify that the withdrawal address indeed belongs to the customer. They advocated various methods on their website, including the following (the website has in a meantime been taken down):

- For customers to take screenshots of their wallets with the destination address.

- For the customer and the business to video conference during the transaction.

- For customers to digitally sign the destination address with the associated private key.

- For customers to return a little of the bitcoins they have received to the exchange or custodian.

- For the business to supply the customer with an address (presumably by possessing an extended public key of the customer).

These kinds of measures would, of course, probably be ineffective in combating sanction evasion (or any other financial crime for that matter), saddle a heavy bureaucratic burden on the Dutch Bitcoin industry, deeply invade customer privacy, and pose increased security risks for customers. It’s also difficult to see how such measures could possibly be justified within the context of a registration regime.[5]

Naturally, the Dutch Bitcoin community protested again. But all the protest fell on deaf ears at the DCB.[6] So, Bitonic decided to take action. They would, under protest, meet the address verification requirements in order to obtain their registration. But at the same time, they would take the DCB to court over these requirements.[7]

The Court Case

Bitonic’s complaint against the DCB was three-fold.

First, Dutch politicians have given a clear indication of what constitutes a registration regime and that the law which implements AMLD5 should be interpreted that way. The address verification requirements imposed by the DCB are substantive requirements which are incongruent with the law. .

Second, address verification requirements are not mandated by the Sanctions Act of 1977, which formed the legal basis of the DCB’s requirements. Bitonic, as most other Bitcoin companies operating in the Netherlands, is already compliant with this law by screening customers or ultimate beneficiaries of accounts against lists of politically exposed persons (or PEPs). This is the same way that banks meet the law.

Third, the policy is at odds with the EU’s “General Data Protection Regulation” (GDPR).[8] This regulation requires that all data collection activities must have a sound legal foundation. As the DCB’s policy on address verification has no such foundation, Bitonic (and other compliant Bitcoin companies) are in violation of GDPR.

Bitonic presented these three complaints in court on March 23, 2021. The judge was hesitant to criticize the DCB too harshly given the complex technical nature of the case. But her opinion did largely come down in support of Bitonic’s complaints, even though she stopped short of stating that address verification procedures were unlawful. She subsequently gave the DCB six weeks to review and revise their policy on address verification rules as part of the registration regime.[9]

Under such pressure, it was impossible for the DCB not to budge. So, unsurprisingly, it informed Bitonic on May 19 that, “after reconsideration”, their address verification requirements do “not do enough justice to the discretion that an institution has to implement this standard in a risk-oriented manner. DNB has therefore incorrectly set the registration requirement as a condition for the registration of Bitonic.”[10]

Essentially, the DCB acknowledged that their requirements as presented were unlawful and should have never been made. It did also stop short of admitting their unlawfulness.

Implications

The court case is of real importance to the Dutch Bitcoin industry.

While the DCB has not abolished address verification requirements entirely, its statement does leave much more room for reasonable procedures. This can save on administrative costs and red tape for customers, offer better privacy protections and security for customers, and ensure that Dutch exchanges and custodians can remain competitive with their foreign counterparts, including those within other EU member states (as far as I know, the Netherlands is the only EU member state that has tried to impose stringent address verification requirements).

Bitonic is immediately removing its most stringent address verification requirements, including the requirement for a customer screenshot or signature over the receiving address.

We will have to wait and see how other Bitcoin companies react to this statement by the DCB. Given that many potential customers have seemingly moved to foreign service providers in recent months out of concerns over security, privacy, and red tape, they would be smart to follow suit.

While the court ruling and the DCB’s subsequent statement are certainly a welcome development, the whole implementation of AMLD5 in the Netherlands has left much to be desired:

- The implementation of AMLD5 into law should have been a fairly straightforward matter. Instead, the government unnecessarily burdened the public arena, and the Bitcoin sector in particular, with more than a year of discussion about the details of the implementation of the registration regime.

- Execution of the law’s registration regime by the DCB should also have been a fairly straightforward matter. Instead, it attempted to impose requirements far beyond the scope of the law. Uninterested in further discussion about the matter, it took a court ruling for the DCB to “reconsider” these requirements.

- While some friction is to be expected (and perhaps welcomed) with regulating a new industry, all of this has posed a far more significant burden on the Dutch Bitcoin industry and user community than was necessary. Companies have lost revenues and some have ceased operating entirely or moved elsewhere.[11] The lost opportunities for innovation have probably been greater: Instead of conducting lengthy discussions with government officials, regulators, lawyers, and judges, time would have been better spent on creating innovative new services and on improving existing ones.

For a country that prides itself on having an open and innovative character, all of the above is certainly unacceptable.