‘Digital Mercenaries’: Why Blockchain Analytics Firms Have Privacy Advocates Worried

The Takeaway:

- Privacy advocates argue that blockchain analysis is essentially blockchain surveillance and, by contracting with governments, firms offering analytics are laying the groundwork for additional forms of mass surveillance.

- Western tech firms aided dictators during the Arab Spring and helped shut down the internet during protests in Belarus, leading to concerns that blockchain surveillance may eventually be used by more authoritarian countries.

- The debate highlights the tension between crypto transparency that encourages wider adoption and the core importance of privacy, a cornerstone of the cypherpunk ideology, to Bitcoin’s future.

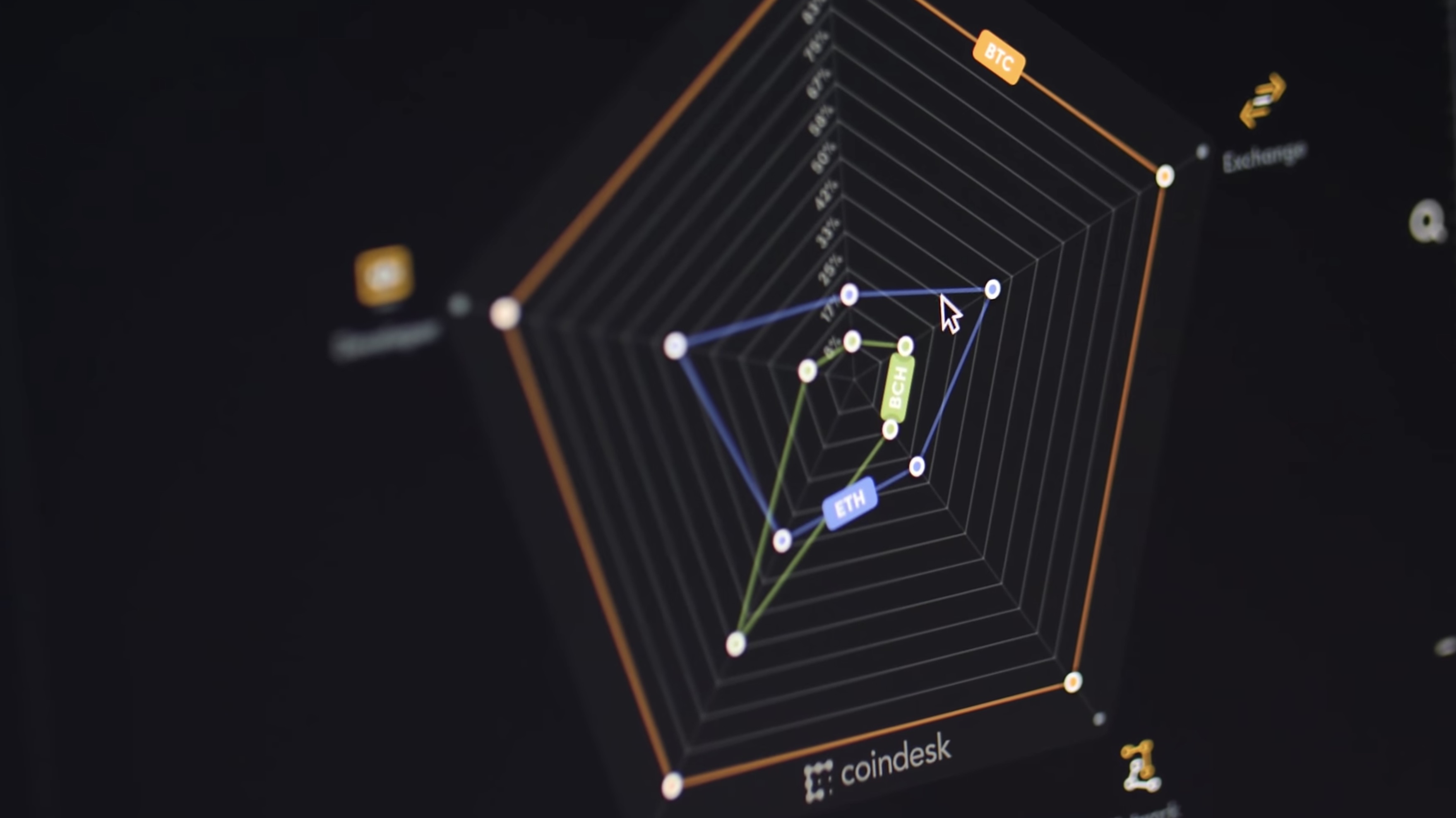

Blockchain analytics has become a fairly common service offering in the industry, used to track, gather and analyze cryptocurrency payments on the blockchain. But privacy advocates express concern that it equates to blockchain surveillance, and it could be used to gather information on people around the world and compromise the privacy of cryptocurrencies.

The debate highlights a tension between know-your-customer (KYC) and anti-money-laundering (AML) compliance in mainstream crypto today and its subversive cypherpunk origins. At the same time, it foreshadows potential conflict between those who see crypto as an investment asset and those who see it as a tool to fight surveillance and circumvent traditional financial models.

“The problem is that these blockchain analysis and financial surveillance companies are going around telling people that they’re doing good stuff. That should not be allowed,” said Alex Gladstein, chief strategy officer at the Human Rights Foundation, and one of the most strident critics of blockchain analytics firms.

“If they’re going to try and make money off government and corporate contracts, de-anonymizing people unconstitutionally, then we should all describe that in an accurate way,” he said. “And if they choose to pursue that line of work, they should have to wear the scarlet letter that goes with it.”

Blockchain analytics firms cash in on federal contracts

There are over 20 blockchain analytics firms on the market, many of which are being contracted by governments, law enforcement agencies and companies such as cryptocurrency exchanges. While it’s generally governments or law enforcement that does the ultimate de-anonymization, surveillance firms are a key tool in tracking movement and targeting individual wallet addresses. And there’s a lot of money to be made by doing so.

As CoinDesk reported earlier this year, Chainalysis, one of the most prominent firms, made more than $10 million in five years from the U.S. government and stands to take in more than $14 million in total. These numbers dwarfed the competition and show an appetite for the firm’s services, including from law enforcement agencies like the FBI and ICE, with whom they had contracts.

Coinbase, one of the world’s largest exchanges, acquired blockchain surveillance firm Neutrino in 2019. Controversy followed when it became clear top members of Neutrino previously led projects for Hacking Team, a startup that aided governments known for human rights abuses.

Earlier this year, Coinbase launched Coinbase Analytics, a product developed out of Neutrino’s tech. In June, it was considering deals with the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

A DEA notice from May said Coinbase Analytics was “the least expensive tool on the market and has the most features for the money,” though redactions made features’ specifics unclear. An IRS notice from April noted Coinbase Analytics has “enhanced law enforcement sensitive capabilities that are not currently found in other tools on the market.”

In July, it was reported that Coinbase had sold its analytics software to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), specifically the U.S. Secret Service. Coinbase has said its analytics product does not and has never used any internal customer data.

These are two examples, but they are indicative of a trend that is only likely to grow as crypto becomes more mainstream, and larger financial institutions, such as banks or PayPal, get into the ecosystem.

What’s at risk

Gladstein and other advocates see this sort of blockchain analysis as an extension of governmental surveillance, along the lines of when the National Security Agency (NSA) was secretly gathering extensive metadata on the American public, not to mention the agency’s work abroad.

Gladstein argues that when it comes to payment processors like Square, and even exchanges, they can make a case they work hard to protect customer privacy. But if you start a blockchain surveillance company (as companies such as Chainalysis, CipherTrace and Elliptic have done), that’s not a defense – because the explicit purpose of the company is to participate in the de-anonymization process.

De-anonymization is a process that has different components, one being the use of the blockchain to trace where funds go.

“Natively speaking, Bitcoin is very privacy-protecting because it’s not linked to your identity or your home address or your credit card history,” said Gladstein. “It’s just a freaking random address, right? And the coins are moved from one address to another. To pair these to a person and destroy their privacy requires intentional or unintentional doxxing.”

On the one hand, Gladstein worries about a future where the government is compelling exchanges to give up customer information, the way Verizon was collaborating with the NSA to conduct surveillance, as was revealed by Edward Snowden.

Many of these practices were later found to be unconstitutional. The mechanism by which the government compels exchanges to give up information is one Gladstein thinks will be heavily scrutinized in the near future.

But he essentially likens blockchain surveillance companies that exist to de-anonymize people to spyware companies.

“They’re kind of like digital mercenaries,” he said. “They’re going to be hired by different corporate and governmental actors to try and figure out who’s who. Ultimately, you know, the sad part is these are usually American companies being hired by foreign actors.”

Grounded in a history of privacy and human rights abuse

That’s not a fleeting concern; it’s one based on history.

During the Arab Spring, western tech firms were cashing in by helping authoritarian governments surveil dissenters. The U.S.-based company Sandvine was also contracted by Belarus to shut down and block parts of the country’s internet as protestors contested the legitimacy of an election that saw “The Last Dictator In Europe” allegedly prevail.

“As a civil liberties organization, our biggest concern is maintaining the privacy that individuals have in their financial transactions, that they currently have with cash, and make sure that that continues in the digital world,” said Danny O’Brien, strategy director at the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF). “So the question is, what are the limits to what governments can do?”

He sees the emphasis on creating further privacy tools as a natural reaction to years of parallel surveillance by governments. Bills like the Earn It Act and the Lawful Access to Encrypted Data Act (both of which push for government backdoors into encrypted systems) have come in response to services like Telegram or Signal, which, in turn, were born in part out of the NSA’s surveillance of unencrypted communications.

Open-source intelligence

O’Brien said outside of overt targeted surveillance, there is the more complicated governmental pursuit of open-source intelligence, where they take data that is out in the open and collect it for intelligence or law enforcement purposes – the tweets people send out, for example, or the photos we post to Facebook.

Similarly, mobile phones have a tendency to reveal where they are, if people aren’t actively forcing them not to, and someone could sit in the background and collect that data.

“In the law and in society, we’re still trying to develop to what extent companies – the public sector and the private sector – can collect that data that is just lying around,” O’Brien said. “And right now, crypto coins that aren’t privacy protected are data lying around in the blockchain. Not only is it public, but it’s replicated in anybody who runs a full node.”

The synthesis and analysis of that information gathered by blockchain analytics companies, according to O’Brien, “are not a harmless practice.”

In terms of block info, he said it might be easy to think of it as a person or company just trawling through and drawing conclusions.

“But one thing that I think is sometimes intuitively hard to grasp is just exactly how much information you can extract from something like the blockchain, which is then used in combination with other bits of either publicly or privately available data, to draw a fuller picture of someone,” he said.

A desire for privacy, contrary to many popular sayings, does not imply criminality. In light of some of the examples previously laid out, a desire for privacy is a natural reaction to a world in which governments and private actors have at times overstepped (sometimes illegally) their mandates and conducted mass surveillance or abused personally identifiable information.

The issues with blockchain surveillance go from hypothetical to real when you consider the ways it might be used outside the U.S.

In Nigeria, protestors of the police are currently using bitcoin to help fund themselves after their bank accounts were shut down, while in Belarus, nonprofits are giving protestors grants in bitcoin. If blockchain analytics firms are brought in, it could contribute to these governments cracking down on these vulnerable populations.

With other firms such as CipherTrace advertising that it can assign “predictive risk scores” to transactions, these products walk disconcertingly close to similar ideas like “predictive policing.”

Crimes tackled with blockchain surveillance

Blockchain analytics serve valuable purposes for law enforcement agencies and have been useful in helping thwart a variety of criminal activities no one should defend.

In 2019, blockchain surveillance firm Elliptic unmasked a terrorist fundraising network (though they’d only received a little over $1,000 worth of bitcoin at the time). In 2019, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) announced the shutdown of the largest online market for child sexual exploitation content at the time, using assistance from Chainalysis.

“Through the sophisticated tracing of bitcoin transactions, IRS-CI [IRS Criminal Investigation] special agents were able to determine the location of the Darknet server, identify the administrator of the website and ultimately track down the website server’s physical location in South Korea,” IRS-CI Chief Don Fort said in a statement.

Chainalysis and CipherTrace products were used by law enforcement when it came to tracking the funds that users were scammed out of during the largest hack in Twitter’s history earlier this year. And in August, the DOJ leveled a civil forfeiture complaint against the holders of 280 cryptocurrency addresses “involved in the laundering of approximately $28.7 million worth of cryptocurrency stolen from an exchange by the North Korea-affiliated hackers known as Lazarus Group.” Chainalysis, in part, equipped the agency with the investigative tools to do so.

Between scammers, criminal and terrorists, it’s apparent there is a value offered by blockchain surveillance.

Chainalysis’ internal decision-making

“Chainalysis supports people’s ability to freely transact and reduces financial friction while protecting society’s most vulnerable people and national security,” said Chainalysis Director of Communications Maddie Kennedy in an email. “Regulators need the appropriate levels of legal authority and oversight and businesses need the tools to tackle the illicit activity that abuses the systems.”

Kennedy said any link from a transaction back to the person or people involved in that transaction must be made outside of Chainalysis because they do not collect any personally identifiable information from exchanges.

“Chainalysis only knows that a particular address belongs to a customer at that exchange, not who the customer is,” she said.

O’Brien of EFF turned the KYC angle around a bit: He suggested that companies providing this service should, in turn, perform some KYC on any client they plan to work with. If they’re selling blockchain analytics as a service, they need to know that the companies or clients that they’re selling to are not using it in a way that will violate human rights.

Chainalysis does engage in such a practice and has a policy of understanding how customers use its data, according to Kennedy. She said that the countries in which the firm sells its product have strong requirements of rule of law and individual privacy. Chainalysis also has an “internal committee and use external data and consultants to approve clients based on a decision framework,” Kennedy said.

She also confirmed that Chainalysis would consider canceling a government or law enforcement contract if the company’s services were being used in an unethical manner, and that they evaluate their government relationships on an ongoing basis.

Chainalysis already works with foreign government agencies that meet its criteria today. However, the firm declined to provide a document outlining such criteria.

A Coinbase spokesperson did not respond to a number of questions regarding Coinbase Analytics, its existing contracts and how the division evaluates its customers.

Is compliance or privacy a choice?

The scope of information gathered for AML and KYC purposes, in addition to information gathered by blockchain analytics firms, has been key to larger financial institutions and payment processors getting into the cryptocurrency space. When each does, as PayPal did recently, it seems to spur a rise in the price of bitcoin.

Tom Robinson, founder of the blockchain analytics firm Elliptic, argued in a recent panel on privacy in cryptocurrencies that the work his firm has done has been key to getting more mainstream adoption of cryptocurrency.

This brings to the fore two potentially competing camps within the cryptocurrency ecosystem – those who trade crypto as an investment asset (and are likely to be comfortable with less privacy for the sake of greater adoption and the subsequent price bump), and those who see it as a subversive tool meant to allow people to transact outside the sight of the government while maintaining their privacy.

Whether those two camps find a way forward without clashing down the line is still an open question.

Josh Swihart, head of growth at the Electric Coin Company (creators of privacy coin Zcash), said he doesn’t think there will or should be a distinction between coins that offer privacy and those that don’t. Individuals and mainstream institutions will have to consider what they want to do on-chain and what to take off-chain to protect their own interests.

“If coins are traceable, there will be actors that include for-profit companies (but not exclusive to them) that will use their technology and data to further their own interests, whether good or bad,” he said via email. “I’m indifferent to whether companies like Chainalysis exist, but opinionated on how they chose to use their technology or who they chose to sell it to.”

In a free society, Swihart said it should be up to the crypto user to determine whether or not they want their financial dealings available to third parties that may want to track them and their history – just as it should be up to the homeowner to close their curtains at night if they don’t want their neighbors to watch them dancing in the safety of their own living room.

Gladstein, for his part, sees the motivating ideology of Bitcoin slightly differently.

“Bitcoin has an ideology and has a mission and is a liberating force,” said Gladstein. “And it is a political act. With everything we know about Bitcoin, that we know about its creation, it’s not about regulation and compliance, but about empowering the individuals against state and corporate surveillance and control.”