DePIN for the Win: Spreading the Benefits of the Gig Economy

As the crypto industry enters a new phase of adoption, many will be wondering which narratives will win this market cycle. Will it be meme coins, scene coins, or AI (vapor)ware? Or perhaps liquid re-staking, ordinals, or maybe doginals, or is it Base? The crypto space is swirling with hot narratives, and even hotter money.

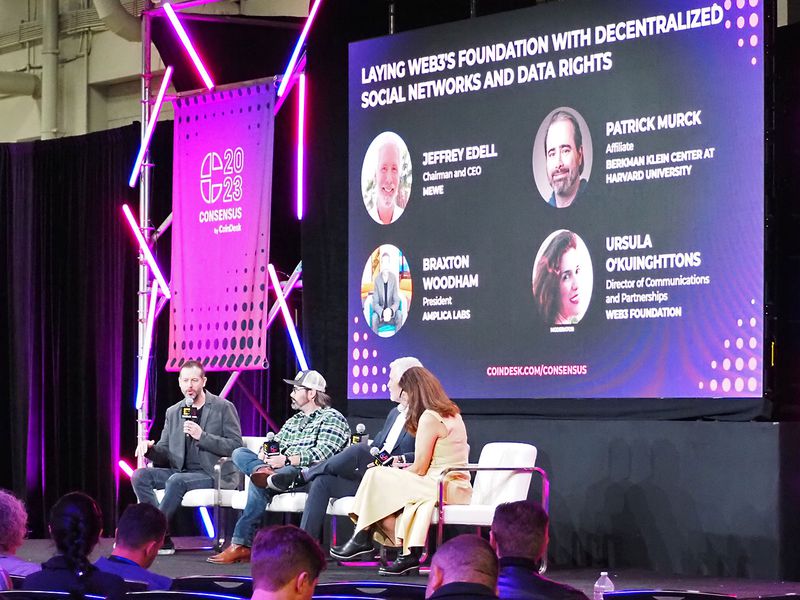

With some luck, this cycle won’t be remembered for any of those narratives. Instead, it will be known for remaking what I will call the “operator economy” (what is more commonly called the “gig” or “sharing” economy). That would spell victory for anyone who has ever overpaid for an Uber or sacrificed health benefits to take on that freelancer gig. And it would be a vindication of crypto itself.

Ivo Entchev is a partner with Youbi Capital, a digital asset VC and accelerator since 2017.

Companies like Uber and Airbnb pioneered the operator economy when they started delivering valuable services using crowdsourced infrastructure and labor. In the process, they proved that this relatively decentralized business model could compete with, and even outperform, traditional businesses. Today, the United States is home to more operating platforms than anywhere in the world, with apps for food delivery, haircuts, babysitters, car sharing, and many more. The U.S. operator economy has produced a stable of unicorns and is on track to be valued in the trillions by 2031. In a sense, the operator economy is becoming The Economy.

From the standpoint of market efficiency and social fairness, the operator economy is a failed experiment. Operator “ecosystems” are rife with monopolistic platforms, predatory pricing (subsidized by venture funds) and supported by an expanding underclass of economically precarious “gig” workers. Gig workers receive piecemeal wages and no overtime, are denied employee benefits like Social Security and health coverage, and must pay out-of-pocket to cover costs of doing their jobs. They are also subjected to various forms of wage theft or discrimination by opaque algorithms that orchestrate their work.

Building equity

Decentralized Physical Infrastructure, or DePIN, promises operator ecosystems that are both more efficient and more equitable. DePIN describes community-driven protocol networks that coordinate hardware-based services with tokens, and its underlying logic is as old as crypto itself. Bitcoin is the prototypical DePIN network allowing anyone in the world to contribute computing hardware towards securing an open distributed ledger in exchange for token rewards. This basic logic informs all subsequent DePIN networks.

Much like DeFi, DePIN’s leading economic benefit is that it dissolves rent-seeking intermediaries and re-distributes their rents to a range of stakeholders. Take Teleport, a DePIN ride hailing app. Teleport coordinates its ride hailing community using its protocol and token incentives, eliminating the need for any corporate, like Uber or Lyft. This returns extractive margins and fees back to drivers and riders in the form of higher wages and lower prices.

Another major improvement is that operators earn an economic stake in the network through the token they accumulate in wages and rewards. As the network expands, these tokens expose operators to pre-IPO venture returns, much like the early miners of the Bitcoin network. In contrast, today’s gig workers don’t receive even basic employee benefits. Tokenization separately benefits the network because it incentivizes early adopters and evangelists, helping to bootstrap the next wave of operators and users.

There are other notable benefits. DePIN is permissionless, meaning that it reduces barriers to entry, draws in a broader range of participants, and expands geographic reach, making it ideal for edge cases. DePIN networks are also transparent and provide more protection against discrimination by algorithm. And because code is harder to halt or censor than a central actor, they can be more difficult to disrupt for political or other illegitimate reasons.

In this cycle, Web3 operators are emerging in a range of industries, signaling that DePIN is expanding and maturing. They include:

Computing operators. Computing operators provide essential processing and communication services. Projects like Aethir Cloud showcase the potential of decentralized cloud rendering networks, allowing developers to build a range of decentralized consumer applications and users to tap into a collective pool of computational power. Similarly, Akash offers a marketplace for cloud services, challenging traditional providers like AWS and GCP with a decentralized alternative.

Data operators. Data operators transform raw data into valuable assets. They deploy hardware to collect and process data, creating datasets and APIs for commercial use. Examples like DIMO and Hivemapper illustrate this trend, with operators gathering vehicle data for insurers or capturing street images for real-time street-level mapping. Beyond mere collection, these operators often enhance data before it’s wrapped into marketable products.

Storage operators. Storage operators ensure data permanence in the Web3 operator economy. Projects like Arweave and Filecoin are offering decentralized solutions for file storage. They ensure that data is not just saved but also remains accessible for future use. These platforms are crucial as they safeguard information against loss and obsolescence, enabling a reliable digital legacy.

Hardware operators. Hardware operators match physical assets with user demand. Take io.net, which connects companies needing AI processing power with a network of GPU providers. Helium operates similarly, linking small cell hardware owners with those requiring 5G connectivity. In the Web3 operator economy, hardware becomes a shared commodity while every participant plays the dual role of consumer and provider.

Growing pains

Despite its recent rise and immense potential, DePIN faces material challenges. Most notably, DePIN networks must navigate the complex regulatory landscape of the real world while remaining committed to decentralization. For example, the mapping service Hivemapper is required to juggle a patchwork of governance, data management, and safety regulations, each with its own set of stringent compliance requirements. These hurdles introduce significant friction, which slows progress towards the desired end state of autonomous protocols.

Finally, if they are to succeed, DePIN network must find ways to protect vulnerable operators from the token volatility and crashes that can accompany a bootstrapped network economy. Ethereum cofounder Vitalik Buterin recently wrote of the moral imperative to protect vulnerable crypto users from token collapses and scams. But his argument is even stronger when applied to projects that purport to empower economically disenfranchised groups, such as gig workers, artists and users in the developing world.

DePIN is a natural place to begin stretching crypto’s social safety net. Assuming that DePIN can solve those challenges, it will revolutionize the operator economy and put crypto’s value, as well as its values, beyond doubt.

Edited by Benjamin Schiller.