Cryptography is a tool that can work in two different ways. It can be used to hide information using encryption or, with the correct information, it can be used to track data. The latter is what people are talking about when they name transparency as the primary value of cryptocurrency or blockchains. Under most circumstances the use of cryptography in financial transactions — cryptocurrency — as a more transparent alternative to fiat currency will end in a major power consolidation for corporate entities and government institutions. But, for as many people who take this future seriously, there is a much less talked about group of anonymous hackers who have proven on a daily basis in the last year that the internet always has new economic opportunities for bad actors so long as the average user continues to make the same operational mistakes.

Webroot, the cybersecurity threat analysis company, has just published their list of 2019’s nastiest malware. From ransomware-as-a-service to intricate phishing scams, cryptomining and cryptojacking schemes, the list indicates that there has been a revival of ransomware attacks, and although crypto attacks have fallen, they will not go away as long cryptocurrency remains valuable.

Research from Webroot’s report pulls from data derived from the billions of networks and devices that they protect on a daily basis. Using machine-learning algorithms, Webroot files and scores over 750 billion URLs and over 450 million domains each day. Bitcoin Magazine spoke with one of Webroot’s security analysts, Tyler Moffitt, to better understand the current level of malware threats they encounter, specifically how much cryptomining and cryptojacking has happened in 2019.

Ransomware Is the Top Threat

Apart from his job at Webroot, Moffitt is a cryptocurrency advocate who has been mining cryptocurrency in his basement since before the bitcoin all-time high of $20,000 back in December 2017. Moffitt uses solar panels, “so luckily the price and power doesn’t matter.”

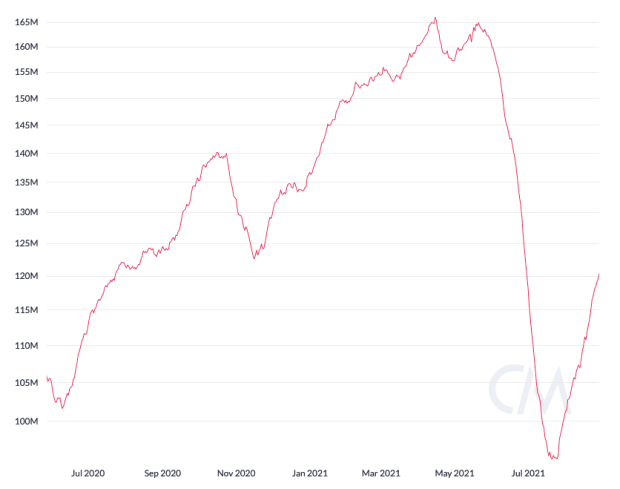

Comparing Webroot’s 2019 report to the same report published last year, the overall threat level looks about the same. Some campaigns have died. Cryptomining and cryptojacking threats have fallen with the overall price drop from bitcoin’s all-time highs at the end of 2017.

This has led to a revival of Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) ransomware attacks popularized by SamSam, the Iranian hacker group. SamSam was tracked and indicted at the end of last year after trying to exchange their bitcoin ransom into Iranian rials on a cryptocurrency exchange. RDP breaches are now the greatest attack vector for small and medium-sized businesses.

Emotet

Emotet is one of the biggest and most infectious forms of malware on the internet today. Emotet is an initial first-stage payload that essentially cases computer environments, analyzing the best way to take advantage of it. In terms of financial damage, probably the nastiest and most successful ransomware attack in 2019 is Emotet followed by TrickBot delivered as a secondary payload that, in turn, deploys Ryuk, an infection that results in a massive network-wide encryption.

GandCrab

After SamSam was caught, GandCrab became the most widely used and financially successful examples of ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) thanks to their affiliate program, now recently terminated, which has allegedly earned more than $2 billion in extortion payouts from victims. Like most ransomware-based attacks, GandCrab infects a computer then holds its files hostage under encryption until the victim agrees to pay a demanded sum.

The RaaS concept is primarily attributed to the Russian-based cybercrime gang, the Business Club. This model doesn’t technically infect anyone. Instead, it hosts the service for a payload, in this case, GandCrab, over TOR, where customers can set their own criteria and generate their own variation of the ransomware to be deployed to their specifications.

Not unlike real business, the RaaS model relies on a script with a built-in specification that automatically sends a 30-percent cut of a victim’s ransom back to the service provider. GandCrab achieved wide success by reducing its cut of the ransom for customers who could infect a certain number of computers per month. Sodinokibi/REvil is another ransomware variant that has arisen in 2019 since the retirement of GandCrab.

Cryptomining and Cryptojacking Threats Subsiding for Now

Though they will most likely never go away, cryptomining and cryptojacking threats have subsided in 2019. This is largely attributed to bitcoin’s price drop since its all-time highs in late 2017 and early 2018. According to the report, this threat has atrophied with around a 5 percent, month-over-month decline since bitcoin peaked in early 2018.

“I’m not going to lie to you. When bitcoin is pumping and surging to 20k, we are seeing cryptojacking and cryptomining payloads spike through the roof. This behavior plummeted with the price in January but then quickly rose again in June,” said Moffitt.

The distinction between these two cryptocurrency mining attacks is that cryptojacking happens on a browser tab when a user visits a website with a script that deploys a cryptocurrency mining cookie. Cryptomining attacks are executable payloads running on computers which first have to be unintentionally downloaded or enabled by a user.

In comparison to ransomware attacks, both types of cryptomining-based hacks are popular in computer environments that run on quality hardware and where hacked victims are less likely to pay the ransom. In the same way, these attacks are much more likely to bring immediate, albeit smaller, financial return. They are stealthy, requiring no consent or knowledge from a victim that an attack has taken place. And as Moffitt points out, “As we know with cryptocurrency payments, there’s no one to report to or complain.”

That someone can fail to notice that their computer is being hijacked to mine cryptocurrency for a hacker seems unrealistic. An infected computer should slow down and its CPU usage should spike. Hackers have found a way around this by scaling cryptocurrency mining according to whether or not a victim is using their infected computer. If a computer is receiving mouse or keyboard inputs, meaning someone is clearly using it, the mining program will scale back to use much lower percentages of a computer’s overall CPU. Then it will ramp back to 100 percent capacity when a user has clearly stopped working at their computer for the day.

Monero

Monero (XMR) is by far the most popular cryptocurrency to mine in cryptomining and cryptojacking attacks. According to Moffitt, this is not primarily because monero is a privacy coin where only the sender and receiver can view the transaction ledger (still a benefit). Instead, it is due to the anti-ASIC or ASIC-resistant nature of monero’s mining algorithm. Set this way by the monero development team as a way to cut out large mining companies such as Bitmain and Dragonmint — who typically dominate or monopolize the hash rate market share of other coins with specialized higher performing mining hardware — Monero soft forks routinely, changing their algorithm so that specifically manufactured microchips quickly become obsolete or less effective than consumer-grade hardware, including laptops, desktops and graphics cards.

“The Monero development team hates the fact that certain manufacturers or vendors will have a monopoly on the type of hardware used in mining pools — basically everyone mining Bitcoin is pretty much using specific hardware from one of these companies — so what Monero does is soft fork every couple of months to change the algorithm so that no one can develop a specific microchip to mine monero effectively.”

The unintended consequence of creating so much opportunity for miners with consumer-grade hardware is that monero has also created a hacker’s dream. It means hackers can profit from mining without any more cost than it takes to deploy a payload, something they are already well equipped to do anyway.

The Coinhive Debacle

One of the best-known examples of hackers finding opportunity in monero’s mining algorithm came from Coinhive’s cryptojacking script. There’s no evidence to prove that Coinhive designed their cryptomining script to be used as malware by hackers. Assuming this is true, Coinhive designed a cryptojacking script for websites to be used legitimately to generate revenue through cryptocurrency mining on an open browser tab in place of online advertising.

“It exploded in September 2017. I would say over 95 to 98 percent of all accounts or campaigns running the Coinhive script were just criminals who had hijacked and broken into web pages they didn’t own and then hosted that script, and then Coinhive collected thirty percent of this,” said Moffitt.

When Coinhive was approached about the illicit use of their script, they immediately cancelled a hacker’s account but did not stop their script from running until they were notified by an administrator of an infected website. This could have been because Coinhive couldn’t distinguish between websites infected with their script and ones who willingly used the service. But the press was bad enough and their explanation didn’t necessarily add up, so they shut down in March 2019, as the entire cryptocurrency market, monero in particular, tested at yearly lows.

Since Coinhive folded, there have been a number of imitators such as Cryptoloot and CoinImp, who also mostly deploy scripts that mine monero.

While cryptomining attacks might be in decline, Moffitt is adamant that they are still very much a threat, “We have blocked over 1 million attempts. There’s still 80 thousand URLs running cryptojacking attacks.”

These attacks are now more focused on free, online streaming service platforms and pornography websites where visitors are expected to remain on a single web page for a much longer length of time than the average visit.

Also, any chance to access the vast resources of cloud computing offers an incredible opportunity for hackers who want to mine cryptocurrency. The most recent attempt to do so that was documented by the media happened earlier this month when a hacker impersonated a game developer to build a vast web of AWS accounts to mine cryptocurrency. Here are two other cryptomining attacks that became prevalent in 2019:

Hidden Bee: An exploit delivering cryptomining payloads, Hidden Bee first started last year with IE exploits and has now evolved into payloads inside JPEG and PNG images through stenography and WAV media formats flash exploits.

Retadup: A cryptomining worm with over 850,000 infections, Retadup was removed in August by Cybercrime Fighting Center (C3N) of the French National Gendarmerie after they took control of the malware’s command and control server.

Threats on the Horizon

While cryptojacking appears to have declined since its heyday and has become fairly easy to block, cryptomining payloads will continue to be a great opportunity for hackers who don’t want to deal with ransomware.

“These attacks aren’t traceable and there’s no way to stop payments from going through, and when you grab cryptocurrency from a mining pool, it’s basically already laundered,” said Moffitt.

Furthermore, he thinks cryptomining is universally appealing for the fact that, as a payload, it can be applied to any smart device with Wi-Fi. Mass IOT infections, such as what was enabled by infected MikroTick routers in 2018, is an attack vector he thinks that will increase. And as the price rises, this increase will snowball.

The post Cryptomining Attacks Remain One of the Nastiest Malware Threats of 2019 appeared first on Bitcoin Magazine.