ConsenSys Faces Shareholder Vote Over Controversial Transfer of Company Assets

For the past three years, one of the most important companies in crypto, ConsenSys, has been engaged in a slow and brutal battle whose outcome could determine its very survival. Following a series of Swiss court rulings, ConsenSys today held its first shareholder vote in two years, which may result in the company taking a stomach-churning leap toward the abyss.

At the heart of this years-long conflict are claims that Brooklyn-based ConsenSys, which develops products on Ethereum, executed a series of corporate maneuvers to transfer the company’s core assets – products like Infura, PegaSys, Codefi and MetaMask, as well as a number of foreign subsidiaries – out of the original Swiss incarnation of the company and into a new American company formed in 2020. This resulted in former ConsenSys employees, who had been granted equity as part of their employment agreements, losing much of the value of their shares, those former employees say.

Ashley Rindsberg, a reporter based in London, is the author of “The Gray Lady Winked,” an investigation of The New York Times.

These former employees have been engaged in a protracted legal battle with ConsenSys that, according to legal experts contacted by CoinDesk, seems to have tipped in their favor. A spate of recent rulings by courts in Switzerland (where ConsenSys was originally incorporated as an “AG” or limited company) have given the case by the 35 former employees fresh momentum.

“This is not just some ‘prior employee getting fu&^ed over’ kind of thing,” said Gabriel Tumlos, one of the 35 former employees who is part of the legal action. “The thing that keeps me going is that at the core of all this is the blockchain story. If this were a DAO or something on-chain, this kind of shadow accounting, the legal arbitrage that companies always do to people, would not have happened.”

The former employees’ action against ConsenSys has proceeded through a number of court cases, including a request for an independent Swiss audit of the transfer of assets from the original to the new company, and a separate case to force a shareholder vote on the transfer of ConsenSys assets. Swiss courts ruled that both requests should be complied with.

Last November, a Cantonal Court in Zug ruled in favor of the former employees’ request for a shareholder vote on the transfer of assets, known as a Sale and Contribution Agreement, which the company appealed. This May, the company acquiesced to the request by the former employees for a retroactive shareholder vote on the 2020 transfer of assets to the new company. The key resolution is a motion to approve action by the Swiss company against the new American company on the basis that the transfer of assets was illegitimate.

Although the official results of the meeting, which took place today in Zurich, won’t be known until later this week, the outcome is a foregone conclusion: Joe Lubin, the company’s founder and majority shareholder, will vote to reject the proposal that the transfer of assets should be unwound, a move that would effectively liquidate the company. Despite this, the vote will allow the former employees to litigate that decision itself in a new legal proceeding.

But the shareholder vote is not the only case in play. In January, the High Court of Zug ruled in favor of the former employees’ request for an independent Swiss audit, a ruling that does not allow for the possibility of further appeal. With a Swiss auditor investigating, the truth will out – and likely very soon.

ConsenSys vigorously disputes these claims. “ConsenSys AG (Mesh) is aware of a small group of former employees behind certain legal actions in Switzerland,” it said in an email.

“Mesh refutes the allegations underlying the legal actions as well as those contained in the factually inaccurate press releases that were self-authored by one of the former employees. Mesh looks forward to prevailing on the merits and refuting the allegations in Swiss courts.”

The company’s current troubles began with COVID. In 2019, ConsenSys founder and largest shareholder Joe Lubin went out to raise ConsenSys’ first round of VC funding, targeting $200 million. As part of the effort, Lubin, a co-founder of Ethereum, delivered a keynote at SXSW, in Austin, where he would declare his mission “to build and fix things essentially on a new trust infrastructure.” But despite that roadshow, COVID jammed a spoke in the company’s fundraising wheel. With crypto plunging into winter, and putting the broader economy in deep freeze, options were quickly leaving the table.

At that time, ConsenSys had a payroll of around 1,300 employees and an attic filled with acquisitions, including an asteroid mining company, a dating app, a music company, an NFT endeavor – and a burn that a company pitch deck projected at $100 million for 2019. The only option left was to take investment from one of the few investors willing and able to put substantial money into the company at that moment. It so happens that company was JP Morgan, hardly a bastion of the decentralization Lubin has long touted.

This, at least, is the more or less official version of events. Lubin, who has a supermajority stake in the company (he can outvote the combined votes of all other shareholders), did what he had to do for the survival of the company. And, indeed, there is little about this version that would inspire a years-long legal battle. But the reality is more complex.

To execute the deal with JP Morgan, ConsenSys crafted a plan called Project NorthStar, designed in concert with the Swiss office of consulting giant PwC. Project NorthStar would call for the creation of a new Delaware C-corp called ConsenSys Software Inc (CSI) and the transfer of all major assets from the original Swiss company, ConsenSys AG (CAG), into the new entity. To determine the share of the new company that the original company would be awarded, ConsenSys had to arrive at a valuation of its core assets, which at the time consisted of Infura, Pegasus, Codefi, a 50% stake in Truffle and MetaMask, along with the company’s subsidiaries in Australia, France, the U.K., Hong Kong, Ireland, and the U.S.

To value the assets, PwC produced what the consulting firm called a “Valuation Report.” The number it arrived at was $46.6 million – total. That sum may sound strangely low, especially considering that these products, identified repeatedly in Swiss court documents as the company’s “crown jewels,” are considered fundamental to the Ethereum ecosystem. But, for the former employees pursuing legal action, this low valuation was key to the design of Project NorthStar.

“What they hired PwC to do was to perform evaluation for a very specific purpose,” said Tumlos, a former CPA specializing in audits, who argued that the kind of evaluation PwC performed is generally used for tax reporting. “The way that we [former shareholders] have understood it is that the goal of any kind of tax evaluation is to minimize your tax liability. That’s why you hire the tax specialist.”

As the report made clear, ConsenSys provided all of the data used for the evaluation, and no independent audit or assessment was performed by PwC. As the report states in its “Disclaimer” section: “PwC has not conducted any audit or due diligence. PwC has not independently verified any of the information received from ConsenSys AG or publicly available and has relied on it as being complete and accurate.”

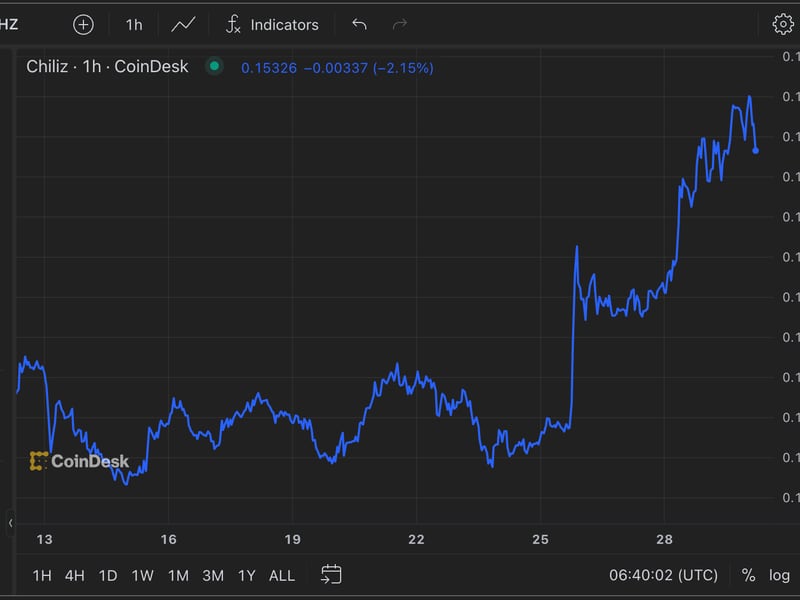

While a Swiss court ruling rejected the former employees’ claim that the PwC report was specifically a tax evaluation, it nevertheless found that the resulting valuation of ConsenSys’ core assets “is not comprehensible.” The High Court for Canton Zug noted that just 14 months after the asset transfer, the new U.S.-based company was valued at $3 billion, 64 times more than the value of the assets PwC had produced. Less than a year after that, in spring 2022, the value of ConsenSys Software Inc. reached $7 billion – 150 times the PwC valuation on the basis of the same core assets.

According to the former employees, ConsenSys refused to provide former employee shareholders with the data or instructions given to PwC to produce the report, leading the court to surmise that “the impression that PwC had been provided with ‘embellished’ data cannot be entirely dismissed…” The High Court for Canton Zug noted that “even the [Swiss] Federal Tax Administration (FTA) could not readily comprehend the appropriateness of the set purchase price of USD 46.4 million on the basis of the PwC valuation report.”

Whatever the valuation should have been for the assets, the question remains whether the deal was appropriate to begin with. With its specifics abstracted, the picture we have is of the CEO and controlling shareholder of a company creating a second company, of which he would similarly be CEO and controlling shareholder, and transferring assets from company A to company B.

“The problem here is there was no shareholder meeting, and there’s no clear approval from the shareholders,” said Jiaying Jiang, assistant professor at the University of Florida Levin College of Law, where she focuses on blockchain and crypto law. “And there’s definitely a conflict of interest when the transaction happened because Lubin was a shareholder and may have been a director of both companies at that time.”

Just 14 months after the asset transfer, the new U.S.-based company was valued at $3 billion, 64 times more

The specifics of the deal complicated matters further. Lubin justified his 52.5% stake in CSI by transferring a $39.1 million loan he’d made to CAG, the first company, as a liability on the books of the newly created U.S. company. This debt transfer would be used to justify the transfer of assets from the original Swiss company in exchange for just 10% of the new company – whose worth consisted solely of the assets transferred.

According to former employees, what ConsenSys calls a “loan” was, in reality, Lubin’s personal investment in the company he’d made over the years. “Lubin considered all of the money that he put into Consensus AG – and this was unbeknownst to anyone actually involved – he was writing everything down as debt,” said Arthur Falls, an early ConsenSys employee and representative of the former employees pursuing legal action against the company.

Swiss law stipulates that if one shareholder loans money to a company, all shareholders must be informed and must be given the opportunity to do the same. According to legal filings by the former employee shareholders, that didn’t happen.

Against this background, the Swiss court found that the motivation for the almost absurdly low valuation is not hard to discern: “The lower the purchase object [the assets] was valued, the higher the value of the assigned loan receivable of nominally USD 39.1 million, which was finally offset, and the higher the personal (direct) participation of Joseph Lubin compared to the participation of [ConsenSys AG] and that of JP Morgan.”

“The basic problem was that the former employees were not represented in the board of directors of ConsenSys AG,” said Rico Florin, a lawyer at Swiss firm Alpine Capital, which has a crypto practice.

“According to Swiss company law, business decisions are taken by the board of directors (and not by the shareholder meeting). Therefore, the former employees had basically no access to the documents about this major deal. The court came especially to the conclusion that Joseph Lubin was in a conflict of interest in connection with this agreement and that he didn’t take the necessary steps in such a situation as e.g. the valuation by PwC doesn’t meet the requirements of a fairness opinion.”

Lubin did not reply separately to a request for an interview. Consensys AG, now called Mesh, provided a statement responding to allegations made by the former employees.

According to the company, “With regards to the ConsenSys Software Inc. (CSI) transaction, the spin out was conducted properly, with the close involvement of globally renowned law firms and an independent valuation by PwC. Although the business fundamentals and operating environment are entirely different today than at the time of the transaction, which occurred during the darkest days of the COVID-19 pandemic, the group would like to apply a retrospective valuation with the benefit of hindsight, which is not how valuations work.”

Lubin decided to denominate his loans to the company in ether, another issue for the ex-employees leading the case. This meant that, as ConsenSys employees built out the Ethereum ecosystem, with the eventual effect of driving up the price of ETH, the value of Lubin’s loan increased.

The decision would lead ConsenSys AG to claim in court filings that Lubin had in fact waived loans to the company worth a staggering $330 million, the approximate figure cited in company financial statements seen by CoinDesk as debt issued by ConsenSys.

According to the court filing, the $330 million figure was calculated according to the price of ETH in December 2020, four months after the transfer of assets had been completed. The ETH-denominated loan put the company in a bizarre logical loop in which the more it succeeded, the greater its debt grew – a debt owed to its founder and largest shareholder. To have any hope of repaying the debt, ConsenSys would have to grow faster than the underlying currency its business was built on.

As it happened, JP Morgan would invest no money in ConsenSys (old or new) despite the fraught corporate maneuvering. Its main contribution was the transfer of Quorum, an enterprise targeted version of Ethereum similar to PegaSys, a product ConsenSys had already built. Nevertheless, JP Morgan received 10% of the new company. Lubin would wind up with a 52.5% stake in the new company, in addition to his 70% stake in the original Swiss company. In the subsequent months, ConsenSys Software Inc would raise a total of $715 million from companies including SoftBank, Microsoft, HSBC and UBS and Mastercard, a fact that the former employees also take issue with.

“The most important assets that are at the core of the Ethereum ecosystem have now somehow been sold to the banks,” said Tumlos. “And, look, I’m not like some kind of idealist. Banks have a place in our future. They do a very specific thing that’s valuable. But we are still in a fight of how do we rebalance the future of our financial ecosystem for the better of all? And something was done here that goes against the ethos, I think, of what we’re fighting for.”

This, too, is disputed by ConsenSys, which points to its longevity and the centrality of its products to the Ethereum ecosystem as evidence of its dedication to crypto ideals.

“Mesh is proud of its history of spinning out projects and its unwavering support and commitment to the broader crypto ecosystem. It is grateful that, despite market downturns and many other challenges, dozens of Mesh projects continue to have stellar success. It will continue on its mission, including defending against such legal actions and public attacks,” the company said in a statement.

Former employees of ConsenSys, some of whom had helped build the company’s core products, in many cases devoting years to the business, would end up with a fraction of the value of their former stake in the company. “I feel that as a shareholder, there has been material harm,” said one early former employee who wishes to remain anonymous. “And, to this date, it hasn’t really been acknowledged. Prior to us getting some momentum in Swiss courts, they wouldn’t even talk to us.”

With the ruling of subsequent Swiss courts coming down in favor of the former employees, this does not bode well for ConsenSys. And, in light of a striking lack of information surrounding the transfer of assets, nor does the pending Swiss audit.

It might be another instance of painful irony that the propriety of actions concerning one of the most important forces in crypto, a champion of decentralization and trustless protocols, will be adjudicated by the most centralized of all bodies: a government court. But disruptive innovation is rarely clean and pretty. And where creative forces are hard at work, as they are in crypto, clashing and contradiction are never far off.

Edited by Ben Schiller.