Casey Rodarmor: The Bitcoin Artist

Casey Rodarmor is not starving, but he is an artist. And like many intellectuals, he cuts a decisive figure. It’s not that Rodarmor is looking to anger; he simply found something that he thought needed doing. Unfortunately, many of his contemporaries have simply not caught up.

If you’re not up to speed: This year, Rodarmor, a long-time Bitcoiner who has made actual code commits to Bitcoin Core, unveiled what he calls Ordinals Theory. In popular parlance, Ordinals are often referred to as “NFTs on Bitcoin.” It’s a phrase that might make Rodarmor, a California native, with as sunny a disposition as he can be ornery, shudder.

This profile is part of CoinDesk’s Most Influential 2023. For the full list, click here.

Click here to view and bid on the NFT created by Rhett Mankind. The auction will begin on Monday, 12/4 at 12p.m. ET and ends 24 hours after the first bid is placed. Holders of a Most Influential NFT will receive a Pro Pass ticket to Consensus 2024 in Austin, TX. To learn more about Consensus, click here.

Click here to view and bid on the NFT created by artist name. The auction will begin on Monday, 12/4 at 12p.m. ET and ends 24 hours after the first bid is placed. Holders of a Most Influential NFT will receive a Pro Pass ticket to Consensus 2024 in Austin, TX. To learn more about Consensus, click here.

“It’s one of the worst acronyms I’ve ever heard,” Rodarmor said, referring to the initialism for non-fungible tokens, in an interview in early November. “First of all, it’s very financial for something that is, like, actually interesting and artistic. And then you tell them what the acronym stands for and they don’t know what it means. Fungible? And then it’s a negation. It’s just terrible.”

He said he strives to use “evocative, interesting language” that “accurately describes” what he’s talking about. That’s why his preferred term for “Bitcoin NFTs” is “digital artifacts.” At times, you might also hear terms like “inscriptions,” or “rare sats” (short for satoshis, the smallest denomination of BTC) or “digital art objects.”

I don’t mean to be a massive pedantic a–hole.

Casey Rodarmor

“I don’t mean to be a massive pedantic a–hole,” he said. But language matters to the high school dropout. His mother is an author and his father a former editor at PC World Magazine. He grew up with words counting for something and a lot of computers around, though he didn’t learn how to code until he mostly taught himself later in life.

“Personally it kind of irks me, but I can’t do anything about it, that people don’t distinguish between ordinals and inscriptions,” he said.

Indeed, what is the difference? It might be best to start at the beginning.

Bitcoin Ordinals vs. inscriptions

First, there was Bitcoin, the distributed computing network that ushered in a private, digital currency called bitcoin into the world. Bitcoin can be sent peer-to-peer, or directly, without an intermediary. It is a protocol and a currency that many users, including Rodarmor, like because there is a finite number of bitcoins (21 million). Altogether, this means Bitcoin is resistant to censorship and inflation.

“I don’t really have a ‘hard money’ or ‘gold bug’ background. But I think it would probably be good if we had money that didn’t inflate,” Rodarmor, born in 1983, said. He added that he became politically aware in his 20s, and that he thinks “the government is incompetent … because they have bad incentives.”

Bitcoiners rejoice. You may not like to hear it, but Rodarmor is one of you.

Indeed, many Bitcoiners this year described Rodarmor as an enemy of Bitcoin, because of the Ordinals Protocol he built that allows people to “inscribe” data onto bitcoins. This, Ordinals critics allege, breaks the fungibility of bitcoin (in a similar way that if a coin is badly scratched, some people may not want to cash it), reduces privacy (a marked coin is an identifier) and clutters the chain (NFTs have a reputation for being frivolous junk).

Rodarmor, obviously, disagrees. He used to be far more willing to engage with critics and to try to educate them. For instance, in a Q&A on the Stacker News forum in January, shortly after Ordinals launched, he responded to a question raised about how inscriptions will interfere with bitcoin’s exchangeability.

That a marked sat is less fungible “is probably sort of true,” he wrote, “but it’s not actually a problem in practice, since everyone can just ignore ordinal numbers and inscriptions.” Ordinals Theory is essentially just a “lens” for properly ordering satoshis in order to view inscriptions, that is, should anyone choose to “inscribe” a “digital art object” onto a satoshi.

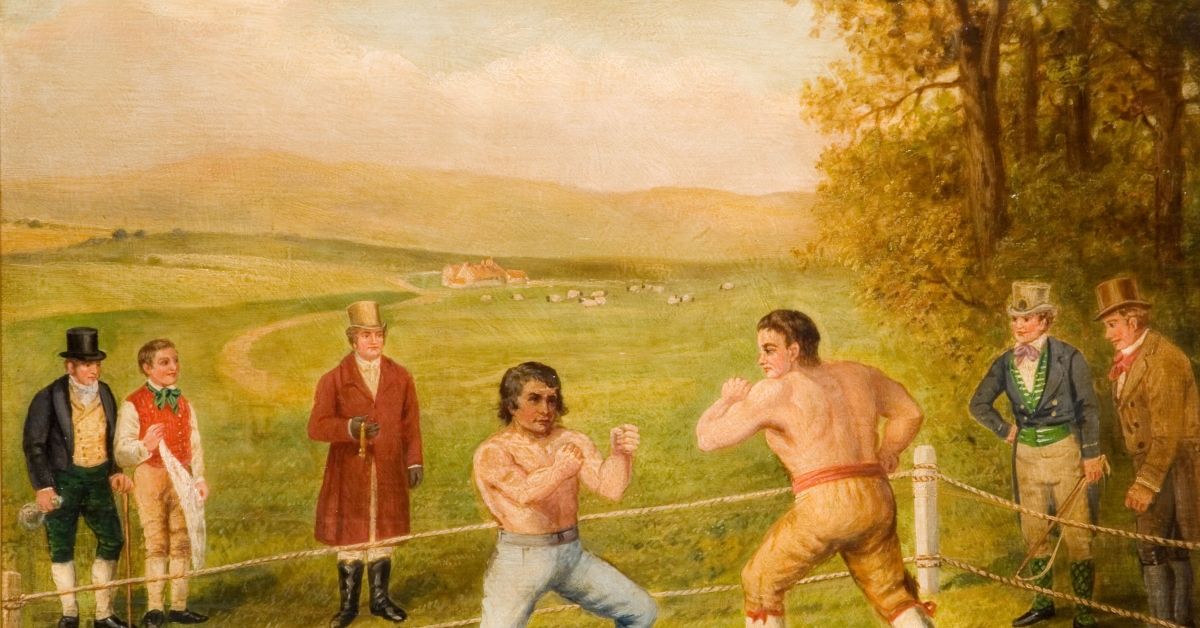

“Satoshis are uninscribed when they come into the world, unstamped metal rounds that can be pressed into a coin,” Rodarmor said in a podcast in March.

In fact, Satoshi Nakamoto, the pseudonymous inventor of Bitcoin, added a similar feature to Ordinals in one of the protocol’s early codebases. Although it was eventually removed, former Bitcoin developer Jeremy Rubin found an “atoms” function that would doctor up a random bitcoin once per block, which would make a scarce asset even more scarce.

Bitcoin’s Taproot update

Likewise, contrary to popular belief, the Ordinals protocol could have been built for Bitcoin beginning on “day one,” Rodarmor said. It has become common wisdom that the ability to “inscribe” these assets was only unlocked after the so-called Taproot update last year, which created a new transaction type for the network.

The Taproot upgrade helped, but the Ordinals protocol was always possible, if only someone had the idea.

Rodarmor’s inspiration came from his interest in generative art, work that is created autonomously using prefabricated algorithms, which has taken on a particular life of its own within the NFT scene, and his desire to create his own generative artworks.

Although he was quite taken by some of the artists working on Ethereum, in particular “Art Blocks” creator Erick Calderon, when he went to code his own smart contract on the system, he walked away feeling disgusted. “Terrible usability,” he said.

So he decided to make his own version on Bitcoin. “The idea behind this project was like ‘Oh, wouldn’t it be cool if I can make and sell my own digital art? And so, you know, of course, I got massively sidetracked” building the protocol, he said. The plan is still to generate art eventually, but at the time of our interview he said he had made “a grand total of one inscription.”

He said these types of all-consuming projects have happened in the past. About a decade ago, for instance, he started working on a musical instrument that used capacitive sensors and a microcomputer that you could play with your hands, not unlike a theremin.

“I went through this whole fabrication phase where I was making silicone pads with embedded conductive fabrics and using a laser cutter to get these different shapes of metal and pouring rubber molds to make control surfaces…” he said. He said he hasn’t touched the instrument since.

There was also a phase where he was making visuals for electronic music, programming everything from “scratch.” Most recently, he’s been making pottery.

Rodarmor said he’s especially attracted to art that serves a purpose; if something is purely “conceptual,” he said it can be boring. At the same time, however, his favorite works are “large-scale, abstract metal sculpture.” Essentially anything that is austere and geometric.

Though he never said as much, it’s clear that coding for Rodarmor is a type of art. Or at least it can be an artistic process. In fact, he described his “processes” for creating spinning pottery wheels and coding trance-like visuals in almost the exact same way.

“It’s about sitting there and writing an algorithm and tweaking it over and over and over again until you get something new,” he said.

Code can obviously be functional, and, in most cases, it is. Software development has essentially been Rodarmor’s only job over the years (outside of a stint of odd jobs working at a clothing store call Mr. Rags, as a film projectionist in Berkeley and video game tester around the time the Gameboy Advance came out before he got California’s version of a GED). He worked for a stint at Google, and later at Chaincode Labs.

Ordinals, for him, was a labor of love. He had saved up a bit of a nest egg working his previous tech jobs that allowed him to fund development. He told me, and has said in other interviews, he’s received tips in bitcoin, but he’s not sure if that “took him out of the red.”

And while Ordinals has been uniquely successful – at time of writing, there have been more than 45 million inscriptions made, generating just under $1 billion in total fees on the Bitcoin network, according to data on Dune Analytics – it can often feel like unappreciated work.

This summer, Rodarmor essentially went dark. After doing months of interviews (including for this publication) and podcasts and reaping the hate of Bitcoiners who despise Ordinals on social media, he felt like he needed to step back. At the time, he said, he wasn’t sure if he’d return.

Part of the issue was just the fundamental unseriousness of the conflict. Bitcoin is an open-source project that anyone can adapt, and Ordinals is a protocol that you can choose to use or not. Getting mad at Rodarmor is as pointless as getting mad at BlackRock for “corrupting” the ethos of Bitcoin by applying to launch an ETF.

Plus, before Ordinals there was no convincing use for Bitcoin that would generate the fees that will eventually be necessary to pay for the network’s “security” once the “subsidy” runs out. Every “digital art object” inscribed on-chain means fees are going into miners’ pockets, who pay for the specialized chips and electricity that keep Bitcoin humming.

“The most interesting thing with ordinals is forcing bitcoin to reckon with the ‘is blockspace solely for native transactions’ debate,” Castle Island Venture partner Nic Carter said in a direct message. “If the NFT community embraces Ordinals as a top-3 NFT system, I could see it being a meaningful share of Bitcoin’s long-term block space, say 20% over long periods.”

The ‘Mad Max of capitalism’

This is the case whether you view inscriptions as art or junk. But in either case, Bitcoin was created to be a free-for-all, the “Mad Max of capitalism,” as Rodarmor said, meaning that if you can pay, you can play and use the blockchain for whatever you want.

This is to say nothing of the legitimate technical advantage the Ordinals Theory represents for NFTs. In almost all cases, on other chains, NFTs are just blockchain signatures appended to media without that media being appended to the blockchain. There have already been cases where an NFT project was lost after the website hosting the content has gone down.

That’s partially why a few NFT projects, including the highly influential Bored Apes series by Yuga Labs, have recreated themselves on Bitcoin. OnChainMonkeys went a step further and abandoned its original series that initially launched on Ethereum.

“Due to their longevity, inscriptions may become the first digital form of high art, and the most important form of digital art ever created,” Rodarmor wrote in the Q&A interview shortly after Ordinals launched.

To be sure, Ordinals are not without their problems. Part of the reason Rodarmor re-emerged from his sabbatical this fall was because a massive flaw with how some ordinals are indexed was uncovered. It was the result of a mistake he made while coding the project, and because Ordinals is immutable it cannot be changed.

Rodarmor calls affected inscriptions “cursed” and initially proposed a way to “bless them” by renumbering the assets, in the first blog he published upon his return. This idea caused rancor among collectors who bought or created inscriptions specifically for their “rare” placement in the Ordinals register.

He and Raphjaph, the developer to whom Rodarmor handed off the ORD protocol, instead decided to address the issue for all inscriptions going forward but not retroactively. The whole process of making a mistake in public code and then working to address the issue by taking on feedback from users is something new for Rodarmor.

It’s also been an “iterative process” learning to live with the love and hate of launching such an influential and contentious bit of software. Rodarmor said he’s an avid attendee of Bitcoin Meetups, and that in person most Bitcoiners either love the idea of Ordinals or are indifferent. It’s only online where the scale and anonymity of the feedback can be overwhelming.

“Casey is the most knowledgeable bitcoiner I’ve ever met, He literally knows everything about bitcoin and has been obsessed with it for like a decade,” Erin Redwing, co-host of Rodarmor’s podcast “Hell Money,” said in a text message. “He would never self-describe this way, btw. He’s very humble.”

Indeed, a BIP, or Bitcoin Improvement Proposal, Rodarmor applied for Ordinals still has not been accepted by Bitcoin Core developers, even though it is not making a formal change to the codebase, just a way to formally document “what has already happened,” he said. He laughs about it nowadays.

“I’m the kind of person that if I’m not working on something, I’m often bored and kind of depressed,” he said “So being back working on it makes me happy.”

Edited by Ben Schiller.