Bitcoin Ekasi: The Township One Year Later

Modeled after Bitcoin Beach, a South African township attests to the opportunities of a bootstrapped bitcoin economy.

This is an opinion editorial by Hermann Vivier, co-founder of The Surfer Kids and Bitcoin Ekasi.

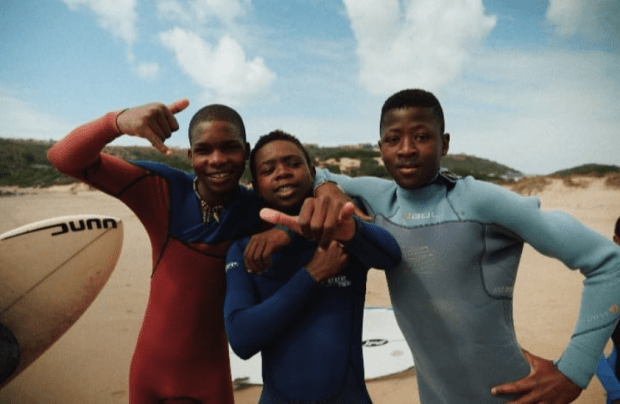

On Aug. 5 2021, Joey Olden and Luthando Ndabambi walked into JCC Camp, a township on the outskirts of Mossel Bay, South Africa. They had a mission: find a township corner store willing to sell them something for bitcoin. Their eventual success later that afternoon (when they bought two cool drinks with sats sent over the Lightning Network) could be called the moment Bitcoin Ekasi was born.

Above: Aug. 5, 2021 — Bitcoin Ekasi is born.

But the seeds that sprouted the project were sown long before. I was first introduced to Bitcoin in late 2013, following the banking crisis in Cyprus. My wife and I operate a surf-tourism business and, because she’s Russian, we’re primarily focused on the Eastern European and Russian markets. The crisis in Cyprus (along with the subsequent bailouts and related confiscation of deposits) affected many Russians and when I came across Bitcoin — thanks to a few early printed editions of Bitcoin Magazine and a friend who’d bought some on Mt. Gox — it grabbed my attention.

On March, 25, 2013, a €10 billion international bailout by the European Central Bank, International Monetary Fund and others was announced. This in return for Cyprus agreeing to close the country’s second-largest bank, the Cyprus Popular Bank, imposing a one-time levy on all uninsured deposits there and seizing around 48% of uninsured deposits in the Bank of Cyprus, the island’s largest commercial bank. A minority proportion of it was held by citizens of other countries (many of whom from Russia) and 47.5% of all bank deposits above €100,000 were seized.

Like all of us, I did not immediately understand what Bitcoin was or how it worked. I still don’t understand a lot of the finer technical details. But, it didn’t take long to realize that, whatever this thing was, if what was written in that magazine were true, those people wouldn’t have had their money arbitrarily confiscated if their money had been in self-custodied bitcoin rather than a Cypriot bank.

After having bought a little bitcoin near the top in 2013 and doing my homework when the price crashed, we started accepting bitcoin payments from surf-trip clients in mid-2015.

The first Russian and Ukrainian conflict had broken out and, as a result of sanctions, in some cases bitcoin was the only way to receive payments. On July 17, 2014, the United States extended its transactions-ban to two banks, Gazprombank and Vnesheconombank and, on Sept. 12, 2014, imposed sanctions on Russia’s largest bank, Sberbank. This affected the ability of both ordinary Ukrainains and Russians to make international transfers and, ironically, our first surf-trip bitcoin payment (in May 2015) came from Ukrainian tourists who were unable to pay as a result of sanctions against Russia.

Fast forward to late 2019. Episode 179 of the “What Bitcoin Did” podcast was my introduction to Bitcoin Beach. The idea of proactively building a circular Bitcoin economy made sense and held great appeal. If Bitcoin was to deliver on its promise, it would have to eventually be used for everyday purposes. And, doing this in a marginalized community, like El Zonte in El Salvador, seemed like a beautiful illustration of the fact that there was no practical reason it couldn’t be adopted anywhere else. It disproved so many of the common falsehoods one hears when talking about mass adoption: it’s too volatile; it’s too complex; it’s only good for criminals and drug dealers, etc., etc.

Listening to that interview with Michael Peterson, I realized that we had the platform to do something similar. So, alongside our tourism business my wife and I co-founded a small non-profit, The Surfer Kids, in 2010. It was created as a donation-based organization and the original idea was to offer tourists some insight into what life was like for 90% of South Africans, without participating in the “let’s-drive-through-the-slum” type tourism. We launched a program that taught surfing to kids specifically from impoverished areas on a weekly basis and allowed a more constructive interaction between locals and tourists. By 2019 The Surfer Kids had grown and evolved into a program serving 40 kids attending surf sessions five days a week, all year round.

In 2021 Bitcoin Magazine gave me a platform to write, which led to a podcast interview on By the Horns and, as a result, The Surfer Kids program received its first bitcoin donation in mid-2021. That was the final piece of the puzzle and the moment when the rubber really hit the road. I could envision the practical implementation of the project, now called Bitcoin Ekasi.

Link to embedded Tweet.

I approached The Surfer Kids’ coaches, specifically our Senior Coach, Luthando, and proposed the idea. He’d never heard about Bitcoin before (other than from scammers) so, first, we’d spend two months discussing Bitcoin, me trying to impart as much understanding as possible within a short space of time. Second, Luthando took that newly acquired knowledge and started talking to the owners of corner stores in the township, explaining the potential practical benefits of accepting bitcoin as payment.

He encountered a lot of resistance. Most shop owners believed (and many still do) that it’s all one giant scam. In fact, most of his time was spent not so much explaining Bitcoin, but simply demonstrating its ease of use. Mobile applications like Bitrefill, Paxful and (more recently) Azteco were invaluable in showing people that, yes, bitcoin was in fact real money. A person’s demeanor would very quickly change from skepticism to curiosity as they witnessed bitcoin — deposited into a wallet on their own phone — being used to buy mobile credit which arrived near instantaneously with Bitrefill. Or withdrawing cash from a cash machine, despite not having a bank account, with only a pin number, sent by a stranger, who was willing to buy bitcoin from them on Paxful. Shop owners were filled with disbelief when we converted vouchers, which they already stocked, into bitcoin with Azteco.

In this way Luthando onboarded our first store (Kwallos Shop, owned by Nosihle and her husband Vuyisa) in early August 2021 and at that point we began supplementing his existing fiat salary with bitcoin, which he could now spend at that store. For two months Bitcoin Ekasi remained nothing more than that. Meanwhile, I continued to educate Luthando about all things Bitcoin and he would go into the township, spend his bitcoin salary buying groceries at Kwallos and speak to other shop owners, demonstrating and explaining the practical benefits of Bitcoin.

It took about three months to onboard the second and third store owners and, in the interim, we began paying bitcoin salaries to our three junior coaches who assisted Luthando in running The Surfer Kids’ program. Up until that point, two of them had been volunteering/working as apprentices, with the hope that we’d eventually be able to afford a salary for them.

The third Junior Coach, Lukhangele, (17) the most senior of the three junior coaches, had been earning his salary in cash. He was (and still is) unable to open a bank account because of a clerical mistake on his birth certificate; his cash salary was often forcibly taken by older family members who used it for their own dubious purposes. Getting paid in bitcoin was an interesting shift for him as he experienced having full control over his own money for the first time. Storing money in a bitcoin wallet, protected by a password, changed the family dynamic. He’s the oldest sibling in the household and he’s the big brother in a fatherless household. Despite still being a school-kid, his salary (of about $150/month) was the single biggest regular household contribution, with the rest of the family mostly relying on social grants and intermittent casual work. Bitcoin put him in the position where he could decide what — and when — he would contribute to the household.

Above – The Surfer Kids Junior Coach – Lukhangele

These sorts of experiences and practical use cases energized me because for the first time I personally witnessed a very real-world impact of what bitcoin could do in someone else’s life. I had experienced it in my own life, but actually seeing financial empowerment happening in front of my own eyes, expanded my perspective on what’s possible with bitcoin. The meme “Bitcoin fixes this” suddenly became real, as I saw it affecting seemingly unrelated social issues in positive ways.

And the more I experienced this, the more motivated I became to drive this project forward as far as possible — because it’s one thing to believe that Bitcoin can change the world, but to see it and experience it right in front of me, that really lit the orange fire inside of me.

It was around that time when some momentum started building, both on the ground and on our Bitcoin Twitter profile, that Michael Peterson contacted me and offered the support of Bitcoin Beach. His idea was to turn Bitcoin Beach into a global movement whereby they support similar projects but allow them to build and grow in their own unique ways. This speaks to the decentralization of Bitcoin itself and stands in stark contrast to the world of fiat donations/funding where, in my experience, many donors expect an unrealistic level of influence and control when donating to an NPO.

Thanks to their support we’ve been able to extend our impact by doing some very exciting things, like launching our kids’ rewards program, appointing a full-time Bitcoin educator in our community, providing shop owners with Bitcoin signage, employing full-time lifeguards to patrol our beaches and prevent drownings and appointing an additional Senior Coach, Akhona, to help Luthando drive this project with more boots on the ground.

In addition, we are now providing staff uniforms to our expanded team of coaches and lifeguards, all of whom earn 100% of their salary in bitcoin and spend it buying groceries from shops we have onboarded.

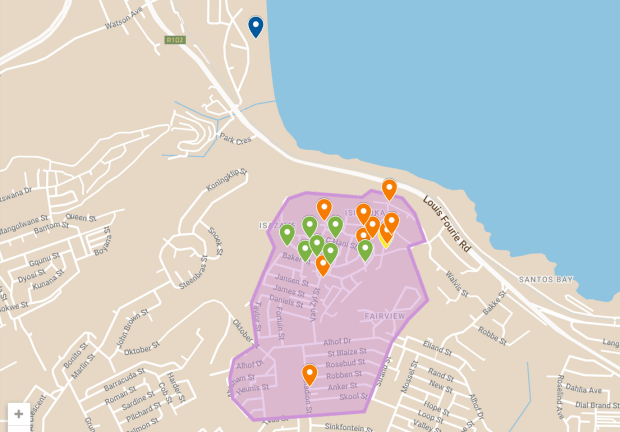

Above: Left to Right — Good Morning Shop (Michael), Good Hope Shop and Isinyoka Shop

The ultimate question, I guess, is, “Why do this?”

If you’re a Bitcoiner, you know why. But it’s my hope that regular people also read this and look at projects like ours and Bitcoin Beach and feel inspired to think deeper and further about the implications of Bitcoin on communities in South Africa and the Global South.

There are two reasons why I’m doing this. First, to support and expand upon the original aim of the The Surfer Kids’ program, which has always been about personal empowerment.

As a recovering addict there is one thing I understand very well, and that’s the fact that change must come from within. The best way to help another is to show them how to help themselves. Anything else creates dependency and, more often than not, has negative long-term side effects.

And so The Surfer Kids’ emphasis has always been on teaching the kids the value of commitment to long-term goals. As that’s the way for an individual to empower themselves: commit to something and stick with it, no matter what. Surfing is fun but inherently difficult to learn and, like Bitcoin, teaches perseverance.

However, operating The Surfer Kids for more than a decade, it’s always felt like a drop in the bucket. There are thousands of people living under horrifying circumstances in that township, and that’s just one of thousands of townships — in this country alone. And we only serve 40 kids.

Introducing Bitcoin as a tool for personal and financial empowerment could, like it did in El Zonte, create a ripple effect in our community. And I’ve already seen that happen in numerous interesting and exciting ways. Those who dismiss the idea that Bitcoin changes a person’s mindset and attitude are either not paying attention, have not experienced the effect firsthand in their own lives and/or have never seen it happen in someone else’s life.

Second, as mentioned earlier, this is another proof of concept. There are very few places in the world where people live under more desperate circumstances than townships such as this one. Unemployment is astronomically high. Illiteracy is rife. Most homes are in fact informal structures built from scrap material and the majority have neither running water inside their home, nor toilets or warm water.

If Bitcoin can work here and be organically adopted in a setting such as this, there’s no reason why it couldn’t be adopted anywhere else. I’d understand if an upper middle class person told me they’d prefer not to use it, for no particular reason other than preference. But don’t tell me it’s because it’s too complex or volatile. If it’s being adopted (voluntarily and with no incentive other than the utility it has to offer) in the circumstances that we’ve described here, then why not anywhere else? And everywhere else?

The fact of the matter is, those are all just excuses. People will adopt it when they need it. When they have no other choice left, bitcoin will no longer be “too complex,” “too volatile” or “only good for criminals and drug dealers.”

And that’s really been the most beautiful thing about this experience. The people whom we’ve seen adopting bitcoin, in the township, have not done so for ideological or philosophical reasons. They don’t care about our Twitter debates. We’ve seen bitcoin being adopted simply because, unlike the rest of society for whom the current system still works relatively fine, for many in this township community Bitcoin is, in many respects, simply the best available option. A personal path to greater freedom and personal responsibility is being learned, one South African at a time.

And when (not if) the current status quo fails or when there’s a major sovereign default or reserve currency crisis, those skeptics who don’t yet see its utility will begin to understand. It is only at that point where they will begin to strongly consider adopting bitcoin.

Essentially, we’re helping to get the lifeboat ready before the ship goes down. Because by the time it does go down, the lifeboat must be sailing.

This is a guest post by Hermann Vivier. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc. or Bitcoin Magazine.