Bitcoin And The Downslope Of Network Effects

With the rise of Bitcoin’s network effects comes the equivalent demise in legacy finance’s network effects.

Bitcoin’s price and ecosystem benefit from network effects.

As more users join, demand pressure increases the price of bitcoin, which in turn attracts more buyers in a self-reinforcing cycle. Similarly, user growth creates a larger market with more liquidity, incentivizing businesses to provide more services, integrations and security, which then encourages new users to join the more robust ecosystem.

Understanding this network effect is important when considering Bitcoin’s place within the greater financial world.

Legacy financial systems also benefit from network effects to a degree, as increased user growth enables expansion of financial services, fostering more user growth. As more customers adopt Visa credit cards due to their widespread use as payment options, more merchants are incentivized to integrate with Visa to access customers, thereby enabling more Visa card adoption.

Network effects are a powerful driver for growth.

However, not all network effects are the same. Each network has its own value proposition, potential growth rate, structural limitations, and barriers to entry and exit. Metcalfe’s Law posits that the value of a telecommunication network is proportional to the square of its nodes. As more users (nodes) join such a network, the number of possible connections increases exponentially, providing an ever-growing incentive for new users to adopt that network.

Although Metcalfe’s Law has limitations beyond communication networks, it still helps illustrate the exponential power that network effects have in our increasingly interconnected world.

A less-discussed phenomenon of network effects is their decline potential. Just as the increase in the number of nodes can add value to a network exponentially, so too can the decline in the number of nodes reduce the value of the network exponentially.

Social giant Facebook has leveraged network effects in its growth, as each additional Facebook user added exponentially more social connection opportunities, thereby enticing more users to join. However, with each user who deletes their Facebook account, the potential number of social connections declines at an exponential pace, a phenomenon I have written on previously. As Facebook users’ news feeds become stale, displaying the same few posts by the same few people, users may abandon the social network due to its diminishing utility, which would make existing users’ news feeds all the more stale in a self-reinforcing cycle.

Network effects go both ways.

This decline potential of network effects was written about by Game B co-founder Jordan Hall, in his piece entitled The Rise and Fall of Networks. In this piece, Hall outlines how companies that benefited from network effects such as Facebook, YouTube and Twitter are potentially more fragile than they appear.

These companies have reached a level of market dominance, whereby they attract an overwhelming share of new users, further cementing their market dominance. This is a powerful network attractor force, which may seem insurmountable for new market entrants. However, in the face of these powerful network attractor forces Hall articulates a different concept:

“Any for-profit entity that is founded on the value of network effects must maximally extract that value to the limit of the network attractor. This produces an ‘extractive repulsor’ force. As the limit is approached, the network becomes poised at fragility.”

This value-reducing “extractive repulsor” force on social networks is most obviously seen in the intrusive ads and the selling of user data. As Hall points out, these forces are anti-valued by the users and incentivize them to leave the network. Users do not join a social media site to see ads and have their behaviors tracked or manipulated, rather, those things are tolerated up to a point.

Less evident examples of this extractive repulsor force can be seen in the onerous restrictions on network use, reduced customer service, intrusions on user wellbeing, or even social consequences, all of which exert downward pressure on the growth of the network.

If too much extractive repulsor force is applied, the network’s growth rate will stop and begin to decline, diminishing its value to its users.

This is the Metcalfe-Hall equilibrium. For-profit networks are incentivized to extract value up to the limit of repulsing the network effects, but no further, otherwise, the network risks causing a potentially exponential decline in network value.

Hall also points out how the decline of a network can be faster than its rise, since the downfall of a network is now also encumbered by the extractive repulsor force.

As users delete their Facebook accounts due to declining social connections, the fact that their newsfeeds are interspersed with intrusive ads will only serve to accelerate abandonment, a point I have written about previously. The precariousness of such a Metcalfe-Hall equilibrium means that for-profit networks that rely on network effects could suddenly begin a downward, self-reinforcing, exponential decline in network users.

Gradually, then suddenly.

In the context of financial networks, it is worth considering the degree to which network effects attract users and value-extraction repels users.

As for-profit entities, legacy financial systems impose extractive repulsor forces in the form of fees, overdraft penalties, and onerous exchange rates. In addition to these forces, there are minimum balance requirements, limited business hours, withdrawal limits, and wait times that encumber the user who seeks to store and exchange value. These things are anti-valued by users, but tolerated to the limit where they remain with the network.

Until recently, the Metcalfe-Hall equilibrium within legacy financial systems has been at least partially supported by a lack of alternatives. Whereas a person can delete their Facebook account and take their social lives elsewhere, deleting their bank account or credit card to take their financial lives elsewhere was more difficult.

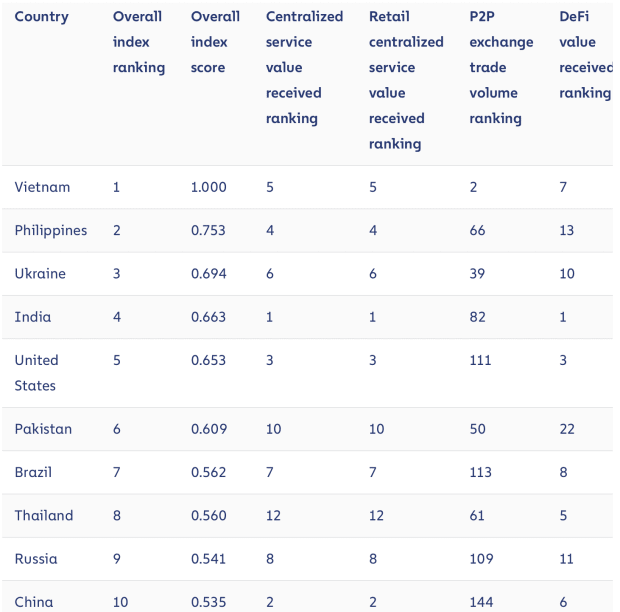

With the growth in the Bitcoin ecosystem for buying, selling, borrowing, lending, and securing value digitally, a new financial network is emerging. This new network offers a completely different approach to fees, wait times, business hours, exchange rates, minimum balances, and withdrawal limits. The marginal user seeking to manage their finances can now do so in an alternate network.

Within the payments space, people gravitate towards bigger credit card providers for their convenience, despite fees ranging from 1.3% – 3.5% per transaction (or more in some markets), and credit card companies having a history of abusing their payment network dominance. However, with the advent of Bitcoin, the Lightning Network, and Lightning-based services such as Strike or recently the Cash App, this equilibrium is poised at disruption.

The video of Strike’s CEO Jack Mallers streaming dollars over the Lightning Network is a demonstration of a fundamentally different payment network. If Lightning Network-based payments can offer final settlement at a lower cost, the marginal merchant may offer preferential pricing to pay via Lightning, or simply restrict or deny credit cards altogether. If more people switch to a Lightning-based payment network, credit card companies may have to compensate for their declining revenues by imposing higher fees on their users, which could accelerate a popular switch to Lightning. This is the downslope of a network effect.

Another notable example is the remittance industry, which enables workers to send money abroad via its networks of offices, agents, ATMs, and websites while extracting value via fees and exchange rates. As more people remit via the Bitcoin network, chasing more attractive fees, wait times, and exchange rates, the legacy remittance industry will face a crisis. Declining revenues may force raising fees, reducing customer service, or worsening exchange rates, which will serve to both depress the network attractor force and amplify the extractive repulsor force.

Mitigating customer loss by improving network robustness is no small feat in the face of a worsening financial position.

The fixed overhead costs of for-profit financial networks can be seen as structural extractive repulsor forces, integral to their business models. Whereas historically people may have gravitated to the largest networks with the biggest economies of scale, those same networks now carry the biggest financial burdens on the downslope of a network effect.

For financial networks, the deleterious impact of a declining network may be less sudden and noticeable at the outset. A large number of customers and merchants adopting Bitcoin-based networks will not immediately diminish the value that legacy financial networks provide to their existing user-base. Credit cards will still be swiped, money will still be transferred, and account balances will still be accessible. However, over time as network attractor forces increasingly pull marginal users away from legacy networks, the fees, wait times, accessibility, and exchange rates will worsen, not improve.

That worsening user experience can be self-reinforcing at an exponential pace and is the downslope of a network effect.

As Bitcoin and the Lightning Network offer alternatives for value storage and exchange with little to no barriers to entry, legacy financial networks will be challenged. Any business that relies on the power of network effects, should recognize the precariousness of a Metcalfe-Hall equilibrium and that declines can be steeper than inclines.

Gradually, then suddenly.

This is a guest post by Matthew Pettigrew. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.