As Justice Is Sought for Do Kwon, South Korea’s Crypto Scene Emerges From Terra Luna’s Shadow

Join the most important conversation in crypto and Web3 taking place in Austin, Texas, April 26-28.

:format(jpg)/www.coindesk.com/resizer/7TcQ2aGqvtDhzfjwpn9vhYzW3zM=/arc-photo-coindesk/arc2-prod/public/2TCZT6PKNFAMNOYKRDMCGIDMZY.jpg)

Emily Parker is CoinDesk’s executive director of global content. She was member of the State Department’s Policy Planning Staff, a writer/editor at The Wall Street Journal and editor at New York Times. She is author of “Now I Know Who my Comrades Are: Voices from the Internet Underground” (FSG). She speaks Chinese, Japanese, French and Spanish.

Join the most important conversation in crypto and Web3 taking place in Austin, Texas, April 26-28.

Terra Luna is back in the news as the United States and South Korea vie for the extradition of Terraform Labs co-founder and CEO Do Kwon, a Korean national who was recently arrested in Montenegro. The Korean crypto community is likely more invested in the outcome, but some actually prefer that Kwon be sent to the U.S. because the punishment might be harsher there.

The collapse of the Terra Luna stablecoin project reverberated throughout the world, causing some $60 billion to evaporate. But the longest shadow fell over Korea, where it remains today.

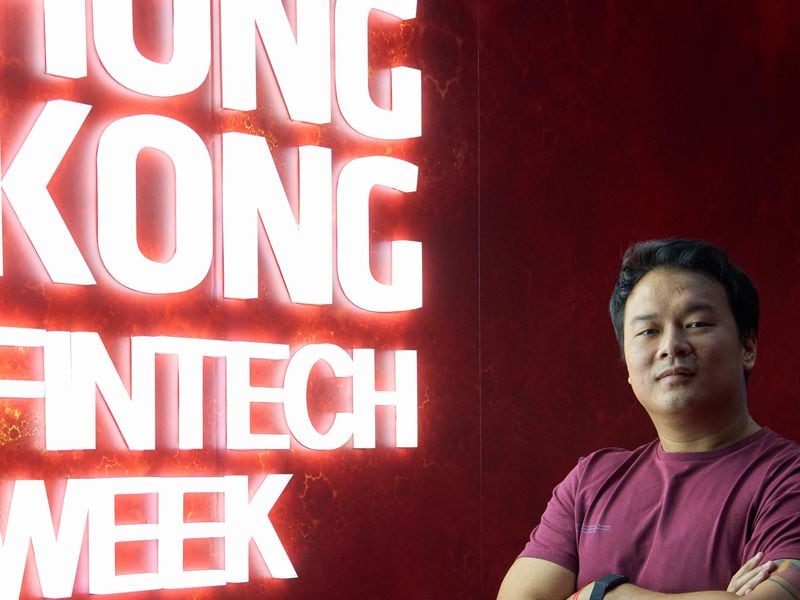

The 2022 crash was all over the local media, which reported that the project had some 200,000 local victims. “Even my grandpa knew about Luna,” said SungMo Park, head of Korea business development at Polygon Labs. Projects that built on top of Terra found themselves homeless, at least temporarily. A once pro-crypto presidential administration started to appear much less enthusiastic. To this day, the state of crypto regulation in Korea is not terribly friendly.

Terraform Labs was based in Singapore, not Korea, but the project played a special role in Kwon’s native country. When I visited Seoul a few months ago, memories of the crash were vivid. I heard about people selling their homes to invest in Luna, as well as speculation that if Kwon had returned to Korea after the crash, he likely would have been killed.

The downfall of a prominent, Korean-born founder clearly had a psychological impact. “Do was a very young Korean leader making a big change in the global scene. There was no software company in Korea that was making that kind of impact on the global level,” said Jiyun Kim, CEO and co-founder of DSRV, which ran a Terra validator in Korea. “He was a kind of north star for Korean crypto founders.”

“Koreans don’t really think Koreans are capable of going global,” said Lloyd Lee, founder and CEO of Hyperithm, a digital asset management firm that is based in both Seoul and Tokyo.

“There were two stars that actually broke that belief. One was [the K-pop boy band] BTS, the second was Do Kwon.”

When it comes to crypto, Korea is one of the most powerful markets in the world. The Korean won is the second most traded national currency for Bitcoin, after the U.S. dollar, according to Coinhills. A report by Korea’s Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) in September of last year said there were nearly seven million registered crypto users in Korea. The digital asset industry market size was nearly 23 trillion won for the first half of 2022, or close to $18 billion at current exchange rates. It dropped to 19 trillion won in the second half of the year, according to a newer report.

There were two stars that actually broke that belief. One was [the K-pop boy band] BTS, the second was Do Kwon

The Terra crash appears to have taken a toll on local crypto trading, though of course there were other factors as well. In the first half of 2022, the domestic virtual asset market showed a decrease of 58% in market capitalization compared to the second half of 2021, according to the FIU. The report attributed this drop to the economic toll of the Ukraine crisis, rising interest rates and decreasing liquidity, “as well as the decline in trust in virtual assets due to the Terra-Luna incident.”

Unfortunately, Terra Luna was not the end of the drama. According to CoinGecko, Korea was the hardest hit by FTX.com’s collapse. Just this month, the Korean exchange Gdac was hacked for nearly $13 million. In December major crypto exchanges delisted the controversial token Wemix, leading to a loss of nearly $300 million in market cap. None of this would be reassuring to regulators and businesses who already suspected that crypto was unsafe.

The Terra Luna crash, among other factors, seems to have had a political effect as well. In last year’s presidential election, candidates adopted crypto-friendly positions in an apparent attempt to win over young voters. The winner, President Yoon Suk-Yeol pledged to restrict taxes for crypto gains and allow initial coin offerings. His win came with a flurry of media headlines suggesting a crypto-friendly administration, with the price of at least one Korean crypto project soaring on these high hopes.

But Yoon assumed the presidency in May of 2022, the very same month Terra collapsed.

“The new government can’t just go pro-crypto when all this Terra Luna happened and people are losing their assets or money, and companies are going bankrupt…and all these social problems are happening at the same time,” Hyperithm’s Lee said. “They can’t just say, we’re going to keep our pro-crypto stance. So they backed away a bit.”

Earlier this year, Korean media reported that lawmakers were working on the Digital Asset Basic Act (DABA), which collectively refers to 17 draft bills that largely focus on investor protection. As of now, none of these bills has passed. “We were on the way to make some new crypto legislation, especially after the new presidential administration started. But so far there has been almost no new regulation, only discussions in Parliament,” said Jongbaek Park, a partner at Bae, Kim and Lee.

Terra Community AMA with Do Kwon (April 2021) (Terra)

At present, the focus of crypto regulation is mostly to prevent money laundering and terrorism. Korea’s AML act was amended in 2020 to include virtual-asset service providers (VASPs). Korean crypto exchanges have to report to the FIU and they are obliged to do know-your-customer (KYC) checks with new clients as well as report suspicious transactions.

Meanwhile, there are currently only five crypto exchanges that trade with Korean won. The government was trying to restrict the number of VASPs to make anti-money laundering (AML) regulation stricter than before, Park explains. So they set up a guideline that if you want to have a virtual-asset service involving Korean won, you should set up some special category of bank account.

“The Korean government tends to place too much importance on the prevention of risks, like investment protection, protection of market stability, rather than to encourage possible innovative effects to the market or community,” Park said.

“AML regulation is good to get rid of bad actors, such as those doing money laundering or terror financing,” Park added. “The problem is the government has not legislated other regulation.”

The arrest of Do Kwon has helped bring crypto assets back into the regulatory spotlight, adding some urgency to a long-delayed process, CoinDesk Korea reported. One crypto-related bill could be voted on as soon as this month, and another could be considered next month. The bills address protection of user deposits as well as the prohibition of the use of undisclosed information, manipulation of market prices and illegal transactions.

“Last year, the Tera-Luna scandal was still unresolved, followed by the FTX scandal. The pace of change in the digital-asset market is very fast, so related bills should be carefully enacted according to the situation,” Yoon Chang-hyun, a member of the National Assembly, told CoinDesk Korea in late March.

“The bill on digital-asset trading (currently pending in the National Assembly) is expected to be passed within the second quarter of this year,” Yoon said. The first step is to enact a transaction law, and the second step is to enact a basic law.”

There was one sign of progress in February, when Korea issued guidance on security token offerings, or STOs. “The Korean government didn’t want to permit token-type securities in general, even though they had designated regulatory sandboxes for four STO projects. These guidelines are a big change,” Park explained. But a more careful look at the guidelines shows they are not as progressive as they first look.

“The fact that the FSC announced STO guidelines is good news for crypto. But if you go into the details of that guideline, they have a restrictive attitude toward the extent of STOs. For instance, they essentially exclude public blockchains,” Park said.

It’s not uncommon for a country’s crypto trajectory to be shaped, at least temporarily, by traumatic events. In Japan, the Mt. Gox and Coincheck exchange hacks spooked regulators and cast a several-year chill over the domestic crypto community. But those same events also spurred Japan to devise some of the clearest crypto regulations in the world. The United States, meanwhile, is still reeling from the implosion of FTX, which dealt a very visible black eye to an industry that already had plenty of detractors in Washington. Partly due to recent crackdowns by the SEC, some crypto businesses are now avoiding the United States.

The dust of the Terra Luna crash has not completely settled in Korea, though Kwon’s arrest does move this story a bit nearer to closure. Several people told me that after the crash, traditional Korean companies became more wary of being associated with crypto. “Before Terra, all the big companies were joining the momentum. Investment banks actually invited us to give them seminars on crypto ETFs or how they can pave their way into the crypto market. But I guess now the attention has become a bit selective,” Hyperithm’s Lee says. “Not all the companies are interested in crypto anymore.”

It is hard to know where Korea will ultimately end up on crypto regulation, but its retail market is still showing its power. Korea played a role in the recent surge of the XRP token, to give just one example, as XRP trading volume surged to billions of dollars on top local exchanges UpBit, Bithumb and Korbit.

“Whenever the next bull market comes, retail traders will be back. I had friends asking me at $60,000-bitcoin if they should sell their house to buy bitcoin. This all or nothing mentality is not uncommon in Korea,” said Anthony Yoon, managing partner at ROK Capital.

Some previous members of the Terra community found other chains. And in the crypto industry, optimism remains strong. “Right now the wave is gaming companies,” said SungMo Park. “And I think the next wave will be entertainment. We are good at gaming and entertainment, and we have all the conditions to succeed.”

In other words, key parts of the Korean market are already moving past Terra Luna’s demise. It may be some time before we see crypto friendly regulation, if it happens at all. But Korean builders and traders are not all dwelling on the past.

“People tend to move on quickly to the next hype or the next incident, in order to keep up with the fast-moving Korean trends,” said Erica Kang, founder and CEO of KryptoSeoul, a community-building team in Korea.

“When a huge, devastating crash happens people are shocked of course and are negatively affected, and they harshly criticize. But then, maybe weeks later, they are back in the game.”

DISCLOSURE

Please note that our

privacy policy,

terms of use,

cookies,

and

do not sell my personal information

has been updated

.

The leader in news and information on cryptocurrency, digital assets and the future of money, CoinDesk is a media outlet that strives for the highest journalistic standards and abides by a

strict set of editorial policies.

CoinDesk is an independent operating subsidiary of

Digital Currency Group,

which invests in

cryptocurrencies

and blockchain

startups.

As part of their compensation, certain CoinDesk employees, including editorial employees, may receive exposure to DCG equity in the form of

stock appreciation rights,

which vest over a multi-year period. CoinDesk journalists are not allowed to purchase stock outright in DCG

.

:format(jpg)/www.coindesk.com/resizer/7TcQ2aGqvtDhzfjwpn9vhYzW3zM=/arc-photo-coindesk/arc2-prod/public/2TCZT6PKNFAMNOYKRDMCGIDMZY.jpg)

Emily Parker is CoinDesk’s executive director of global content. She was member of the State Department’s Policy Planning Staff, a writer/editor at The Wall Street Journal and editor at New York Times. She is author of “Now I Know Who my Comrades Are: Voices from the Internet Underground” (FSG). She speaks Chinese, Japanese, French and Spanish.

Learn more about Consensus 2023, CoinDesk’s longest-running and most influential event that brings together all sides of crypto, blockchain and Web3. Head to consensus.coindesk.com to register and buy your pass now.

:format(jpg)/www.coindesk.com/resizer/7TcQ2aGqvtDhzfjwpn9vhYzW3zM=/arc-photo-coindesk/arc2-prod/public/2TCZT6PKNFAMNOYKRDMCGIDMZY.jpg)

Emily Parker is CoinDesk’s executive director of global content. She was member of the State Department’s Policy Planning Staff, a writer/editor at The Wall Street Journal and editor at New York Times. She is author of “Now I Know Who my Comrades Are: Voices from the Internet Underground” (FSG). She speaks Chinese, Japanese, French and Spanish.