A Year After FTX: The Lesson Europe Has Fixated On

November 11 marked a year from the day FTX formally declared bankruptcy, and, of course, nine days from Sam Bankman-Fried being found guilty on all criminal counts against him and sentenced to lifetime imprisonment.

The symbolism of the trial is debatable. It is sometimes talked about as a policymakers’ catharsis, as it could allow those that engaged SBF with trust to conclude that justice has been done and move on. An alternative view is that FTX exposed the crypto market for its vulnerabilities and, now the hype is gone, the market ain’t coming back.

Dea Markova is a managing director and head of digital assets at Forefront Advisers.

These are both overly simplistic. Having an adequately regulated crypto-asset market would allow policymakers to attract more risk-averse and institutional capital to the asset class. Yet, it is true that the downfall of FTX framed regulatory conversations around the world and made them overly adversarial. In London, in Brussels (where I’m based) and at international fora, the industry needs to explain how it would ensure against an FTX-size catastrophe.

The lessons we already knew

In reality, the majority of the crypto industry is aligned on the answers – proper authorization, proper custody, and proper client asset segregation. These are core principles of running an investment business, and there is no real argument over them (leaving to one side the U.S. regulation-by-enforcement reality).

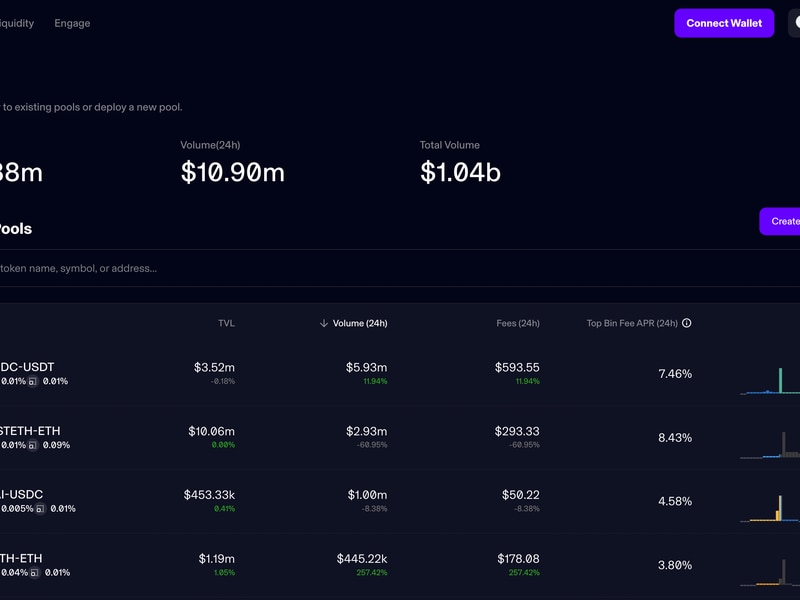

The move many exchanges made towards proof-of-reserves in principle supports client asset segregation, although it has limitations as an accounting technique. More broadly, in 2023, in markets with strong regulators, exchanges are keen to be seen as responsible.

For anyone with a financial services background, this is a natural next step. It is not a paradigm shift. The FTX collapse just made the penny drop faster for service providers that might have had second thoughts.

In November 2022, such requirements were already in train in the E.U. under the bloc-wide Markets in Crypto-assets Regulation (MiCA). By the time the FTX saga unfolded, the ink was dry. Any subsequent MiCA updates are just part of the long administrative process that precedes the publication and application of E.U. rules.

That is why Brussels policymakers spent the past year telling each other and the rest of the world their incoming rulebook would have prevented an FTX-style collapse. For the most part, this is true. Also, it has to be – the part of MiCA which safeguards exchanges will not be reviewed for another five years or so, and it cannot be seen as already out of date.

Those following MiCA closely would know that there is a still ongoing process of writing supplementary “technical rules.” If it were a national process, this would be the difference between the law itself and the implementing technicalities coming from the regulator.

FTX politicized this process in the EU. It was Europe’s last chance to make sure the screws are tightened as much as possible. But the technical rules cannot go outside of the parameters already set in the top-level law. We are almost at the end of the rule-writing, and not much of what has come out of the last year has been unexpected or, dare I say, draconian.

On the subject of properly splitting up assets and activities, there is an outstanding question how much is enough. Especially when one company is an exchange, has its native token, and offers lending. This remains a debate at international level – where the SEC coordinates and seeks to influence other market coordinators.

This question will not stand before the EU for the next few years, but it may come back and it may also reverberate around the world.

The lessons we didn’t learn

The biggest disagreement FTX left behind is also the most basic one. What is the crypto-asset market is good for, what value does it bring to society given it clearly brings some risks.

While we may brush it away and say it is not up to regulators to pre-determine market innovation so long as it’s safe, we must recognise that writing and implementing the safety rules is a massive effort.

The industry should not hide behind the narrative that regulators lack knowledge. This is no longer the case for many authorities around the world. However, if we don’t want to default to risk-aversion, taking a chance on an industry needs to be politically justified. Therefore, answering the value-to-society question matters.

There are many industry answers to this question but they usually come back to disintermediation and decentralisation. This is the promise of blockchain in various shapes and forms.

To regulators, however, these words translate to avoiding responsibility and preserving anonymity. Soon, they will also translate to inability to detect a carbon footprint. Even though EU authorities have a clear agenda to limit the natural monopolies of Web2, a decentralised Web3 is not being discussed as the answer in the corridors of power. The cost of having an anonymous (or pseudonymous) and unregulatable DeFi ecosystem is too high.

If the industry is to move away from this polemic, perhaps non-custodial services and anonymous services need not be coupled together. This choice goes to the heart of why crypto was invented, and many may disagree.

Yet, crypto advocates will have a much easier time explaining how the technology that allows users to own their funds and their data is not the same technology that allows money laundering and terrorism financing.

Edited by Ben Schiller.