A $1,200 Baseball Hat? Why Disco’s Swag Is ‘Prohibitively Expensive’

Do you remember The Jetsons, the futuristic family from the eponymous 1960s American animated sitcom? In the show, household appliances programmed to know family members’ intimate preferences helped the characters navigate each segment of their days, from breakfast to bedtime routines.

Disco, a metaverse company focused on consent-based digital identity, is working to create a similar vision for the metaverse. And it starts, according to co-founder and CEO Evin McMullen, with the perhaps-less-sexy but nonetheless foundational concept of user-owned data.

As McMullen points out in a recent podcast interview, The Jetsons, who regularly utilized robot sidekicks, didn’t ever wait in line or fill out forms to make their preferences known. Jane simply awoke to a closet of freshly ironed clothes, and George’s toothbrush robot simply “knew” how much toothpaste (and presumably what flavor) to place on the bristles.

“They had personalized experiences everywhere they went,” said McMullen in the episode. But how?

The answer is data. On the internet, data and identity are basically synonymous — and valuable. An individual’s online behavior — their purchases, browsing history, social groups, user names, pronouns, passwords, primary languages, biometrics, etc. — create a digital body of information telling a story about who that person is.

Disco wants to encourage individual consumers to take back control of their data by incentivizing them to move it from siloed, company-owned platforms to user-owned digital wallets that serve as the key to unlocking online experiences.

There’s just one problem: Consumers are kind of lazy and used to the frictionless experience of single sign-on services like Amazon or Facebook. Even if people are convinced of the value of user-owned identity or spooked by controversies like Facebook’s infamous Cambridge Analytica lawsuit, which exposed the release of some 87 million users’ data, there’s currently little incentive to transition away from today’s company-owned, or “federated,” identity model to one where users are our own data custodians.

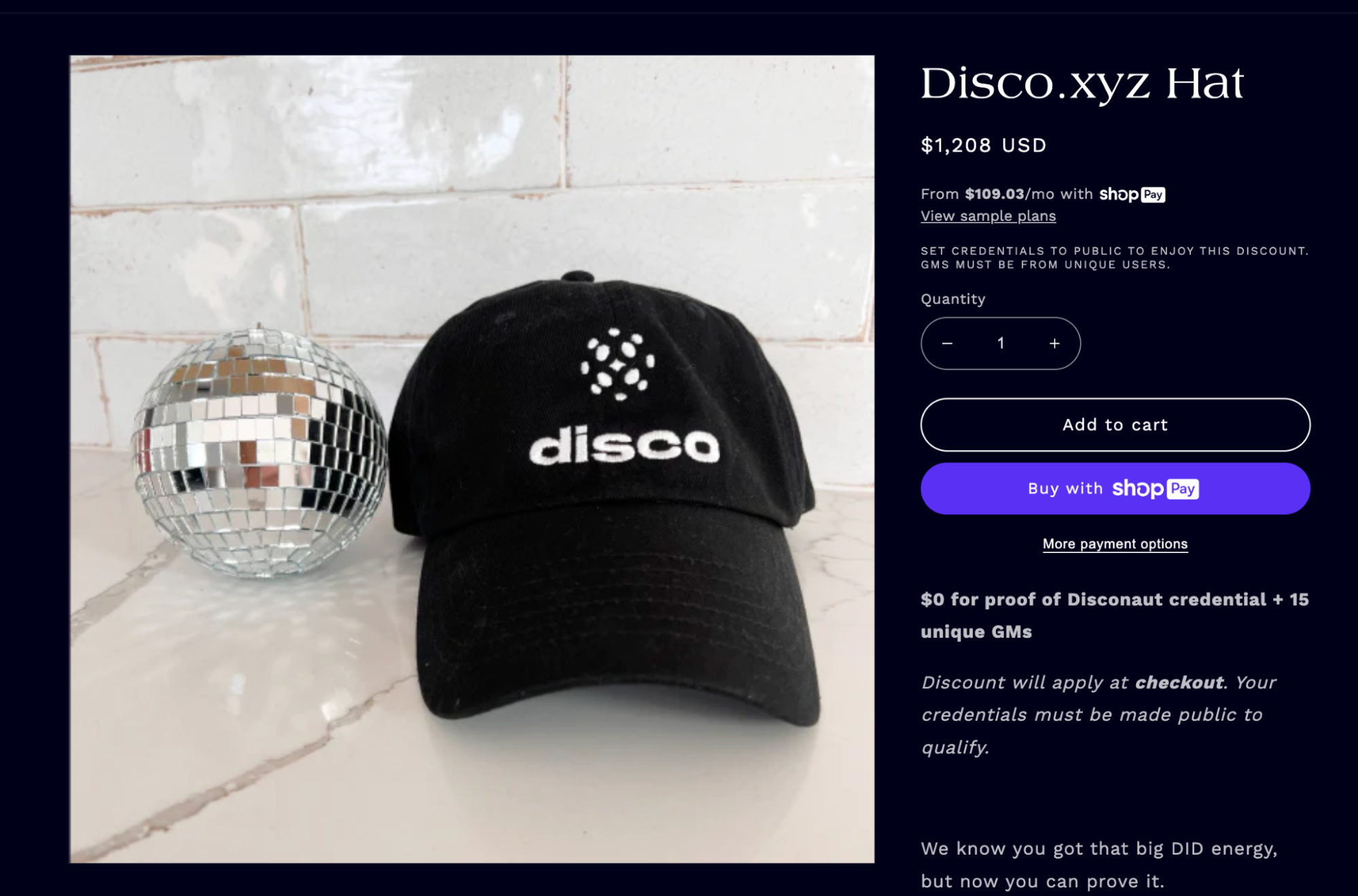

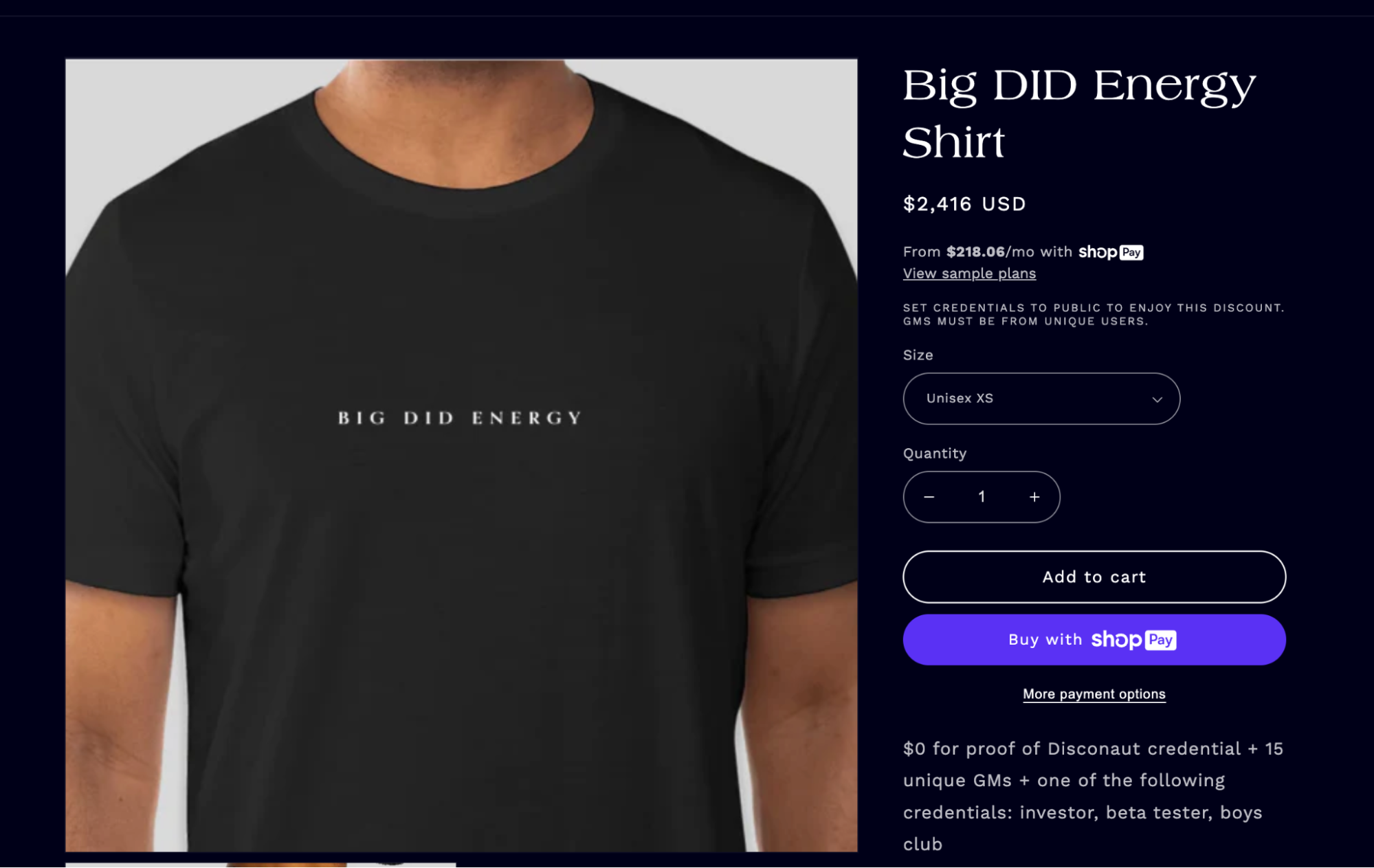

But they are motivated by gamification, status and money. Here’s where $1,208 hats and $2,416 T-shirts advertising “Big DID energy” (“DID” is an abbreviation for “decentralized identifier”) fit in. Disco is making its swag free for users who earn it — and prohibitively expensive for everyone else. McMullen calls this strategy a “meme” to help people grasp the potential of Web3 and feel inspired to take back control of their data. Even those who work in the blockchain industry, she argues, aren’t yet fully realizing the potential of user-owned identity.

“When we originally came up with the idea, the price of ETH was around $1,200,” she said. “So we thought that 1 ETH would be a good price because that’s often the price of blue-chip NFTs.” However, she noted, the Disco team couldn’t find an easy way to sync Shopfiy with the real-time price of ETH and apply the discount codes accordingly, so the team slapped a $1,208 price tag on its hats and doubled the price for shirts.

Verifiable credentials and decentralized identity management

“One of the challenges that I’ve learned over the years is that helping folks in Web3 realize our ecosystem is more than just what you can see on chain … is a little esoteric for a lot of people to grasp,” McMullen recently told CoinDesk.

“Our identity is a co-created verb,” McMullen said. “It is a living, ongoing experience that we co-create with the people and parties around us as a function of how we interact.”

McMullen argues that not all consumer data should live on the blockchain. Instead, we ought to use the full breadth of cryptographic tools to enjoy the functionality of token-gated experiences without requiring that all information about oneself is published as an immutable token, such as a non-fungible token (NFT) or soulbound token (SBT).

One such tool, known as a verifiable credential, offers an off-chain alternative that can authenticate aspects of consumer data without publishing it publicly. “In the same way that a token on chain can unlock access, an off-chain credential with the very same keys that I use on chain can unlock experiences,” McMullen said.

A concept well-known by long-time technologists and cryptographers, verifiable credentials are relatively new to the general population. Disco describes them as a way for any third-party entity, such as a university, employer or government agency, to issue secure credentials to a recipient without revealing sensitive data in the process. In a scenario that pro-privacy technologists hope might happen in the near future, a university could issue a diploma through a platform like Disco, which an employer could verify without the need to access more information than is required to verify the requirements of the job.

McMullen says using verifiable credentials may help consumers prevent the mistake of putting sensitive information — particularly about minors — on chain. This may also lessen the risk of discriminatory practices, such as revealing a person’s age, religious background or ethnicity when it is not required.

“There are not a lot of women I know who would feel comfortable putting their home address on a billboard in Times Square,” McMullen said. “Yet, putting it on the blockchain is more public and more permanent.”

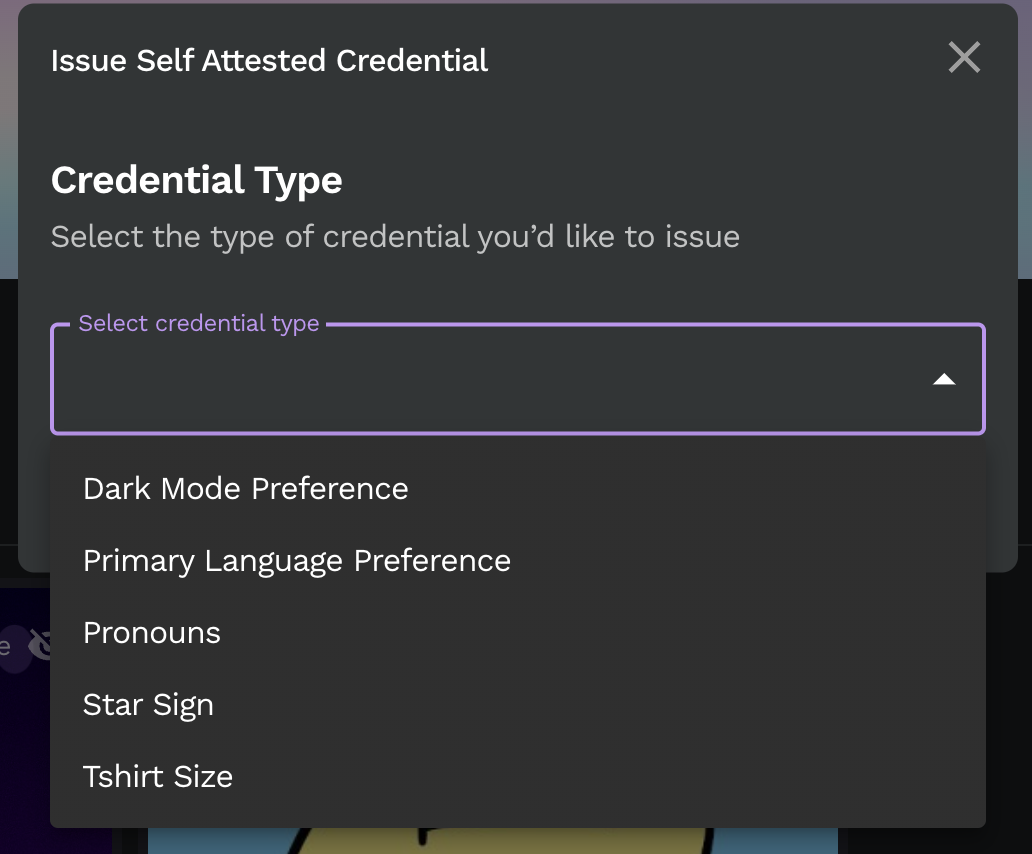

To help consumers grasp this concept, Disco has opened up its API to beta testers, inviting them to create user-owned “data backpacks” containing credentials that they may choose to share or keep private. These credentials may contain personal information about each user’s identity, along with lighthearted social credentials that exist more for the purpose of fun and status, such as the “GM” (slang for “good morning”) credential. Individuals who have completed Disco onboarding and set up their data backpack can redeem their credentials at checkout for free merch, minus shipping and handling. Those who want to pay in USD, well, will have to pay a lot.

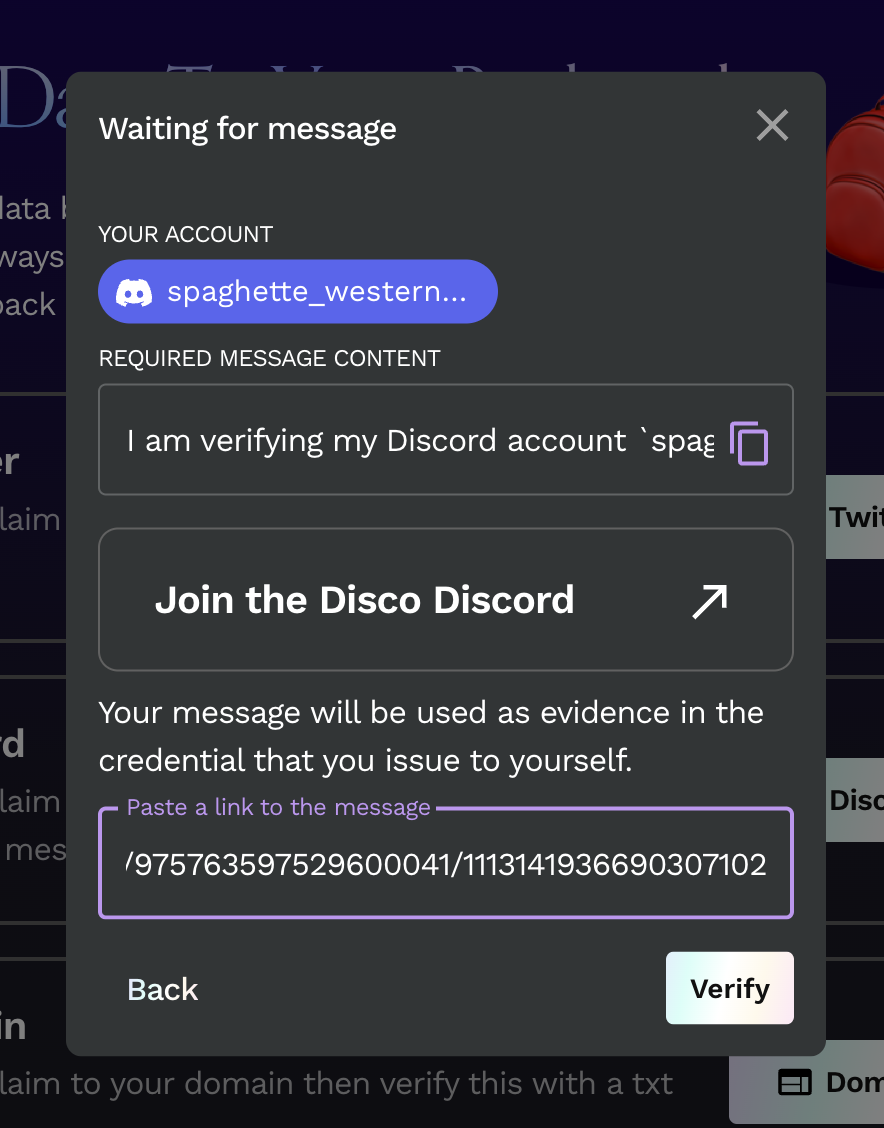

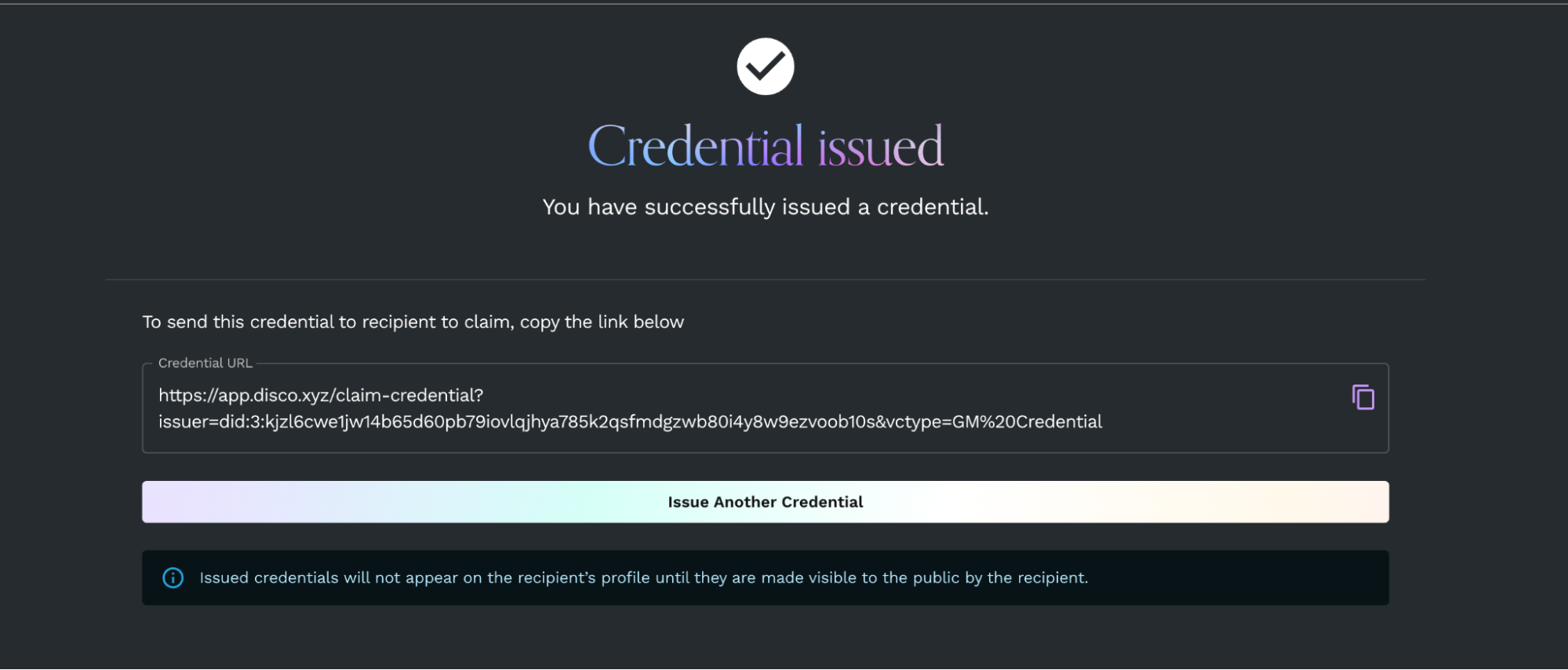

The process of issuing a credential looks like this:

Step one: Create a backpack and complete onboarding

Signing up for Disco requires showing proof of owning keys to a third-party profile, such as Discord or Twitter.

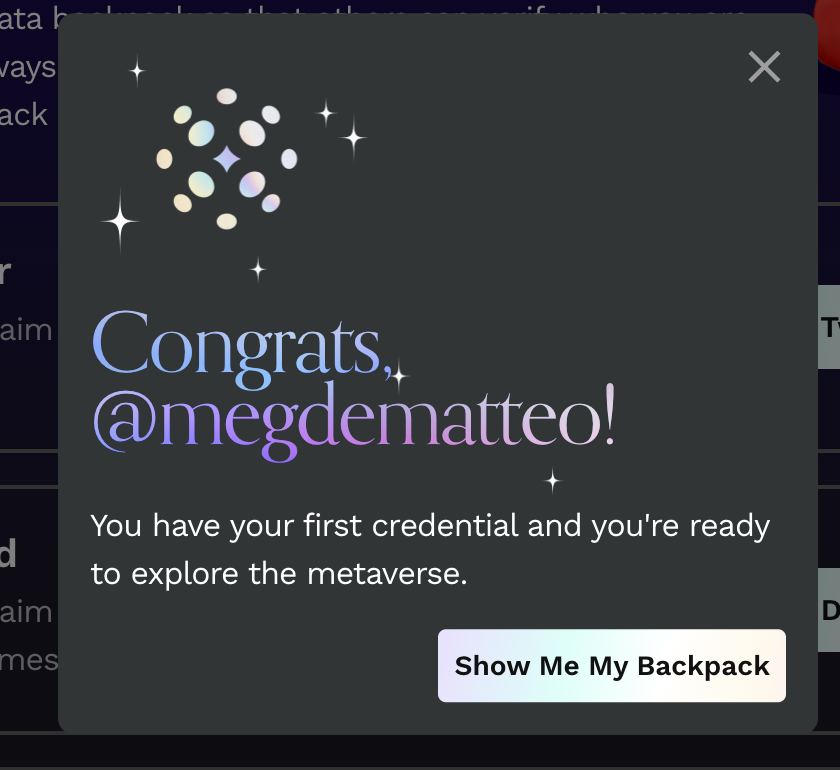

Step two: Receive your first credential

Once you complete onboarding, you will receive the Official Disconaut Credential and be able to receive GMs from your friends. By default, credentials appear in your Disco account as private, but as a consent-first platform, users can toggle public visibility on or off depending on their preferences.

Step three: Add more credentials

Personalize your account by adding details about yourself, which you can share however you like.

Step four: Issue credentials

Send “GM” credentials to fellow Disco users.

Sending 15 unique GMs will qualify you for some free merch, like this $2,416 t-shirt.

Step five: Shop for merch

Depending on the number of credentials you’ve earned, you’ll be eligible to choose from Disco caps, t-shirts and more. Make sure your credentials are set to “publicly viewable” for Shopify to redeem your free merch. You can do this in your data backpack under the specific credential and clicking the eye icon in the top right hand corner.

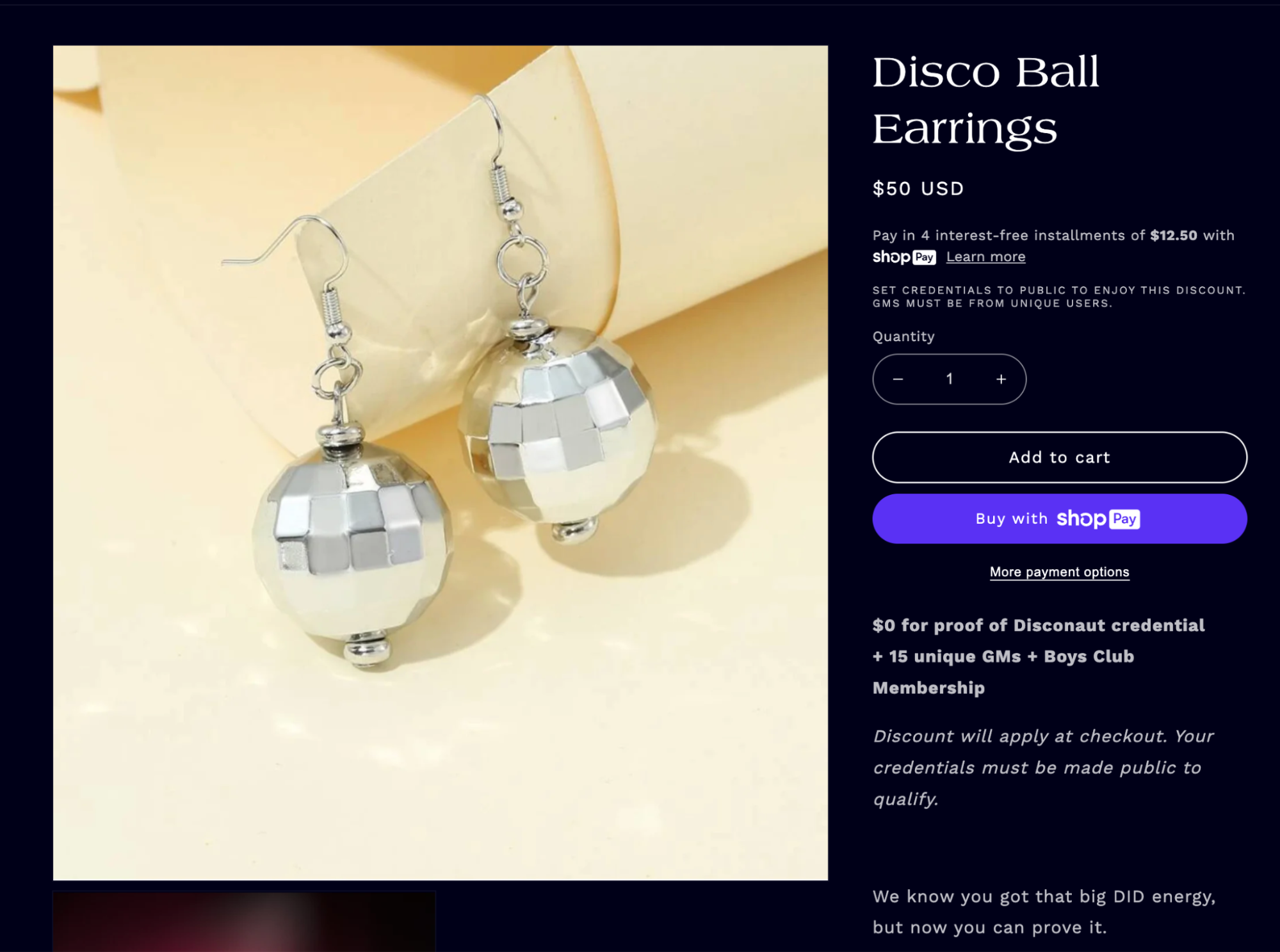

Additionally, owning NFTs from certain partner communities may also qualify you for special merch deals. For instance, these disco ball earrings are $50 USD, or 15 unique GMs, for Boys Club members.

Embracing the learning curve

It may seem like Disco is making consumers jump through a lot of hoops for some earrings, but that’s kind of the point. “The swag store is using the Disco API and checking users’ data backpack to see if they have the right credentials to enjoy a discount,” McMullen explained.

While the process may seem clunky compared to our more familiar social media platforms, McMullen argues that embracing the learning curve is essential, calling the tendency to store personal information on blockchain an “expensive overshare” that often comes with high gas (service) fees.

Fortunately, we don’t have to reinvent every new aspect of decentralized identity, as some legal frameworks already exist to help guide decisions about what information should exist online (and therefore on the blockchain). McMullen pointed to the Child Online Privacy Protection Act, enacted in the U.S. in 1998, and the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), effective as of 2018, among others.

While she noted that such laws may not be wholly comprehensive, nor universally liked among technologists and consumers, McMullen emphasized the responsibility of early Web3 builders to handle data sensitively.

“Building tools that can endanger others is not what we’re about at Disco,” she said. “It’s very important to introduce consent-first data.”

According to McMullen, Web3 enthusiasts tend to think of blockchain as a panacea solving for all aspects of consumer privacy, when in actuality, blockchain is simply a distributed database of information. Disco’s mission is to help individuals to understand and decide what should and should not be on chain before those decisions about our digital identities are made for us.

Edited by Toby Leah Bochan.